Why Women Don’t Run for Office. And How Business Schools Can Help.

Last year, an investigation by Politico found that women are still significantly less likely to run for office than men, even after the 2016 election galvanized many of them into political action. The top three reasons cited were:

- They don’t see themselves as candidates.

- Many often have to be asked, nay convinced, to run.

- They doubt they can do the job.

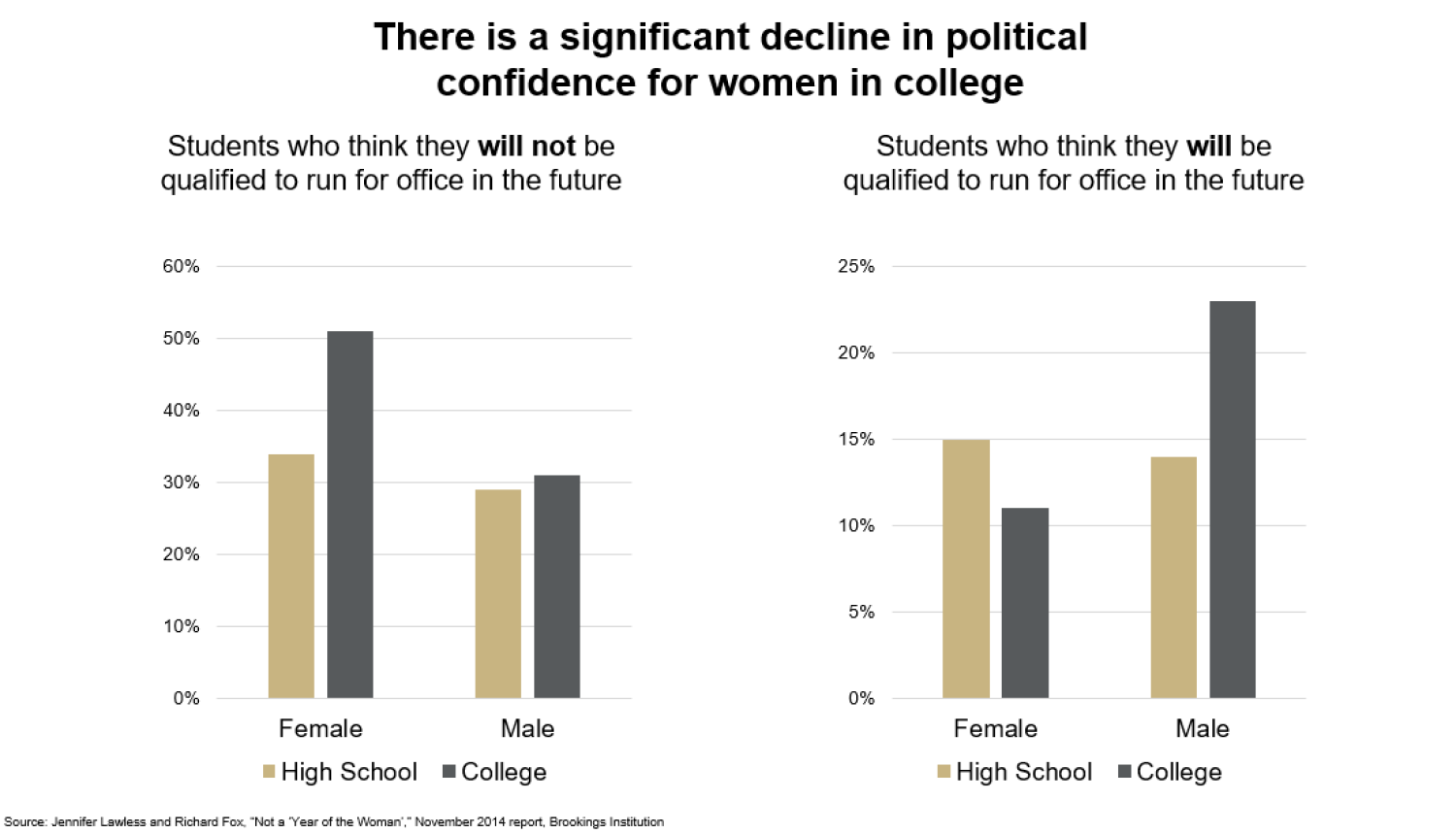

The story is similar for college-aged women. A recent survey of 2,100 college students indicated that college is when the gender gap in political ambition widens. Young women were less likely to be encouraged to run for office by anyone, particularly their parents. They were also more likely than young men to perceive they were “not qualified” to run for office, mostly due to lack in confidence.

Stefanie Johnson, associate professor of Organizational Leadership and Information Analytics at the University of Colorado Boulder Leeds School of Business has closely studied unconscious bias in the evaluation of leaders and leadership. Her research also confirms that women across generations tend to rate themselves as less effective leaders.

We asked Johnson and two of her colleagues from Leeds, Liz Stapp, a lawyer and instructor of Business Ethics and Social Impact, and David Hekman, associate professor of Organizational Leadership and Information Analytics, to weigh in on the challenges they see for women running for political office and leadership and what role they see business schools having in encouraging young women’s political ambitions.

Leeds School of Business: According to Politico, high school boys and girls report almost equal interest in politics, but the gender gap opens up in their college years. While only a third of high school girls doubt they’d ever be qualified to run for office, it jumps to half when they hit college. Why do you think this is?

Stefanie Johnson: When you’re 15, you can believe you can be anything: a professional athlete, supermodel, CEO, politician, but by the time you are an adult, those possibilities start to fall away. You start to weed some of those things out as you learn more about who you are. There’s no doubt that more women don’t run for political office because there are not many women in political office.

Liz Stapp: Research has shown that the best predictor of academic and career success is seeing someone in a leadership role with whom you identify. They [young women] don’t see many women in positions of power or authority as their instructors in college. The message, subconscious or not, that they’re taking away from that is there’s going to be a reason why I’m ultimately not going to be able to advance.

David Hekman: College women are starting to figure it out. … Women realize there’s a cost to ambition. Whereas for men, there’s not, and men intuitively realize that as they ascend through hierarchies.

LSOB: Is likeability a factor in women’s political and leadership success? Why or why not?

LS: Absolutely. Stefanie did research on this. She found if you are an attractive female who does not demonstrate traditional personality traits, you are the most harassed or looked at the most negatively by your male colleagues.

DH: Power and likeability are negatively correlated for women, whereas it’s positively correlated for men. The more power I would get, the more likeable I am. Politics is the use of power, so women will know this. If I go for power, I’m sacrificing likability. Do I want to do that? Maybe. Maybe not.

SJ: I have found that women need to be likeable in order to be successful. If people don’t like you, you’re not going to make it. For women to succeed, they have to demonstrate they can do the breadwinning, masculine things while still showing that they confirm their gender roles.

There are some studies that show if a woman is described as successful, she is rated negatively. In a masculine job, it’s even worse. But then, if you describe her as successful in a masculine job, and mention that she does something feminine, such as ‘has kids’ or ‘knits’ — those little hints that show she is not a gender-role violator — then people’s attitudes turn more positive.

LSOB: How do we address people’s bias that one gender is better than the other in politics and/or leadership?

LS: Until you change the people in the power positions, women’s activization in politics or the workplace hits a ceiling because ultimately the people with the power are still going to be men.

DH: Women are fed up, so more are running. If they win, and we have a record number — that would be great — it could begin to change. Really, it is about changing the way we see the world. We have biases as a culture. If we do not fundamentally believe that women and men are equally good, our behavior will never change.

SJ: How do you know a black swan exists until you see it? How do you know women can run for office, be politicians, the president, if you’ve never seen it happen? Women don’t see themselves as CEOs and politicians because there are so few of them. And the ones that there are, are characterized in such extremely negative ways because they’re usually seen as gender-role violators.

The more women we get into office, the more that breaks down the stereotypes. When it’s not such a rare phenomenon to have women in office, then young people start to realize that it is possible, and maybe they want to do that job.

LSOB: What role can higher education, particularly business schools, have in encouraging and preparing women to pursue political careers and/or other forms of leadership?

LS: Mentors are essential, and it doesn’t need to be a woman mentor. Women need a mentor who sees them for what skills they can bring to the table and doesn’t put them in a box that is threatening. We need support across genders. That would go a long way.

DH: Role modeling; mentoring programs. Have younger women partner with women leaders and learn how to navigate.

SJ: We need to create an environment where women can feel comfortable, and that means having women role models in the classroom. We need to have case studies that reflect more than one gender. We need have more speakers in classes that are women. … and create good mentoring relationships for our business students with leaders from the community that are men and women, so they have that kind of support going forward.

So that means, we need to put forth efforts to attract and retain women in business schools and create a space for them to really thrive. That’s what we’re trying to do here at Leeds.

Considering women are graduating college at higher rates than men — and they are also more likely to study in fields that provide great skill sets for political offices and leadership, such as law, business and management — perhaps this is the entry point to persuade more college-aged women to run for office. (Fact: They earn nearly half of all undergraduate degrees in business.)