How Business Schools Can Offer a “Purple” Solution to Shrinking Public Support of Higher Ed

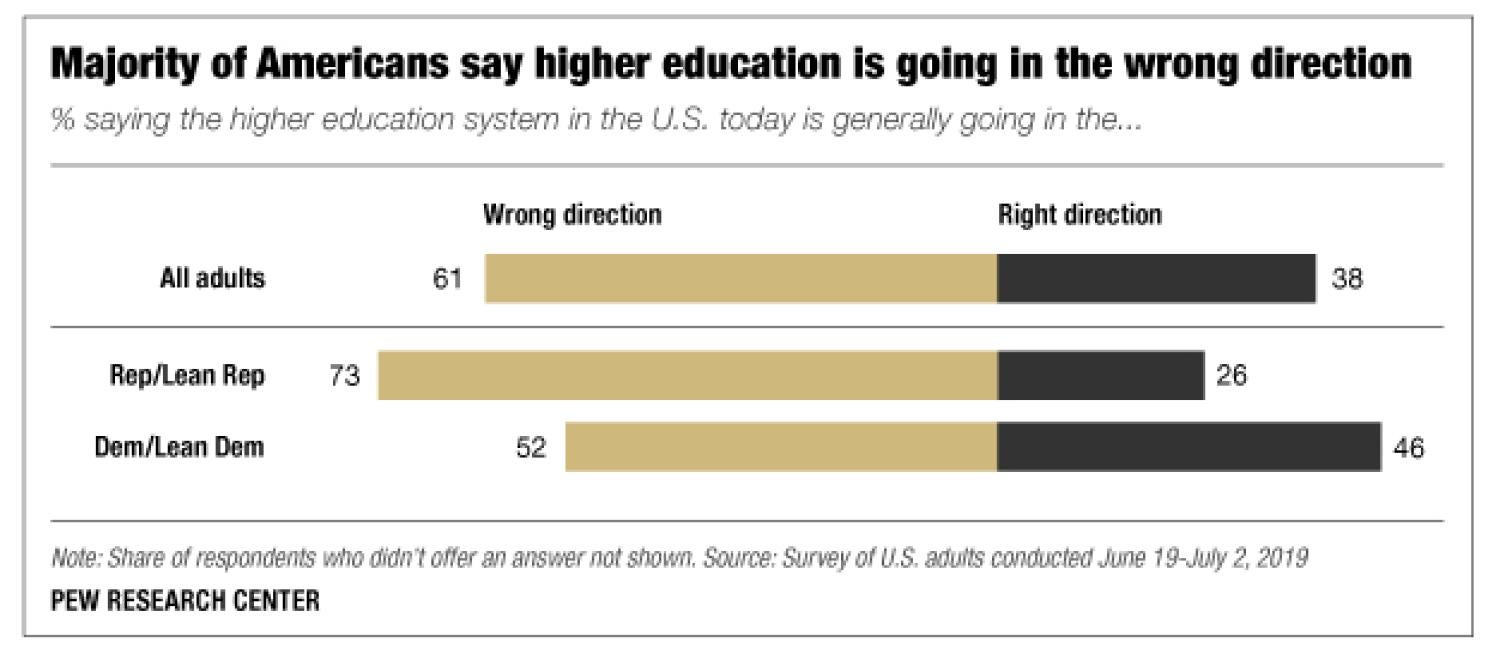

A recent poll from Gallup indicates a sharp decline of confidence in U.S. colleges and universities among U.S. adults. The decline is strongest among Republicans, whose confidence level dropped by 17 percent. Similarly, a Pew Research Center survey found last year that six-in-ten Americans believe higher education in the U.S. is headed in the wrong direction. Republicans in particular are concerned about a liberal bias and expressed concern that professors bring political and social views into the classroom. Constituents from both parties are worried about rising costs—as well as tuition being too expensive. We posit that business schools have a unique opportunity to reverse this trend of skepticism and dissatisfaction. First: a deeper look into the drivers.

Rising Cost of Education

According to statistics from the College Board, average cost of tuition outpaced the rate of inflation by more than 3 percent in 2018, continuing a trend that has been troubling for decades. Coupled with recent headlines that paint multimillion-dollar projects on campuses as “extravagant spending,” the reputation and value of colleges and universities are in question. And as public support declines, so has state and local funding, which only grew “modestly” in 2018, as states struggle to provide funding for public institutions that meets the cost per student.

Concerns Over a Liberal Bias

Political conservatives are concerned that left-leaning faculty are pushing a liberal agenda in the classroom, and in fact, a study published by the National Association of Scholars in 2018 demonstrates that political affiliation of tenured faculty is left-leaning. Furthermore, 86 percent of college presidents agree that the perception of a liberal bias harms the public’s—and in particular, Republicans’—views of colleges. For public institutions especially, this is a problem, as voters and political leaders can negatively impact funding.

Are business schools at public universities uniquely positioned to help? Two trailblazers weigh in.

Public business schools should recognize these trends as an opportunity to enter the conversation. We are in the unique position of being located in the heart of “liberal academia,” while also grounded in a traditionally conservative discipline of business. Business schools have the opportunity to be a “purple” solution to perceptions of political bias on campus by educating students about ideas such as free market economies traditionally associated with conservative ideology. They can also provide programming that brings value to traditionally conservative areas, like rural communities and small towns, and start to change perceptions about the value that higher education brings to the broader community and economy.

Dr. Sharon Matusik and Dr. Idie Kesner, two forward-thinking leaders at public universities, are also the first women to lead their business schools. Both know a bit about breaking down barriers and changing public perceptions. And they have made big strides in building the reputation of their respective business schools: Matusik as dean of the Leeds School of Business at the University of Colorado Boulder and Kesner as dean of the Indiana University Kelley School of Business.

Leeds School of Business: Is there a unique role business schools can play in ameliorating partisanship, especially as it relates to higher education and higher education funding?

Sharon Matusik: As entities whose very purpose is to equip students with the skills to work in and influence global business, and therefore, the economy, business schools can use their strengths as a way to positively impact the public lack of confidence in higher education from within and potentially attract more funding by garnering bipartisan support in their activities.

Idie Kesner: Rather than venture into public discourse about the issue of partisanship, we have relied more on actions. For example, our university has engaged in extensive community service and outreach (both students and faculty) in an effort to show how our business school contributes to state and local communities.

At the university level, this manifests itself in a large-scale program in economic development for rural communities(i.e. the 11 economically underdeveloped counties surrounding our city), and it also includes work on university-defined “grand challenges” regarding issues such as the opioid epidemic and environmental sustainability.

SM: Likewise, CU Boulder is working to better highlight outreach activities of the business school related to economic development. At Leeds, we offer such programs around entrepreneurship throughout rural Colorado to help small-town residents improve existing small businesses or become inspired to start something new. This gives people the tools to address opportunities in their own community, while at the same time improving their own economic well-being. We also provide programs such as free tax preparation for low income families in our community. These initiatives are a way to communicate our school’s value to legislators and taxpayers, regardless of their political affiliations.

LSOB: Do you think business schools can bridge a partisan decline in confidence of higher education?

IK: I hope business schools can contribute positively to building confidence in higher education. The Kelley School is certainly trying, but it’s difficult for individual schools to do on their own. One possibility is for business school deans to work together, finding ways we can contribute to joint communications in which we share what business schools are doing to make an impact at the national, regional and local levels.

SM: Business schools are inherently well suited to generate market solutions to socioeconomic and environmental issues that affect everyone. Leeds teaches students-as-future-business-leaders that it’s entirely possible to have a very successful for-profit firm that also creates social value. We have many successful graduates who are making a positive impact in the world through their business ventures, and faculty whose research on topics such as the role entrepreneurial ventures in addressing environmental challenges shows how economic and social value creation can go hand in hand. At a foundational level, we are teaching our students how to create jobs and enhance economic vitality over the course of their careers, something important to everyone. And by also identifying the positive impacts businesses have on the community, we can do a better job of illustrating the value of (business) higher education to all across the political spectrum.

I do agree with Dr. Kesner. Joining forces with other business schools can help us activate bipartisan constituents throughout this great nation.

When you consider all the practical applications, resources and tools that business schools have to offer, there is much to be optimistic about. Business schools are in position to not only impart real world skills that add meaningful value to a college degree—which both conservatives and liberals can agree on—but they can also help rebuild the public’s confidence in higher education from the inside. Together, business schools can be an even greater force for change, politics notwithstanding.