Conceptualizing Consciousness in Consumer Research: A Brief Summary

When consumers think about explaining the actions of themselves and others, it is very common for them to look first at the relationship between their thoughts and those actions. They often assume that the thoughts and images they have in mind (a.k.a., the contents of consciousness) actually cause action (for example, someone might say to herself, “I thought about buying this dress, then I bought the dress. Therefore, the thought caused me to buy the dress”). In this paper, Williams and Poehlman argue that consumer behavior researchers make the same mistake and that the vast majority of research on consumer behavior assigns too big of a role of conscious thoughts as the most important causes of behavior.

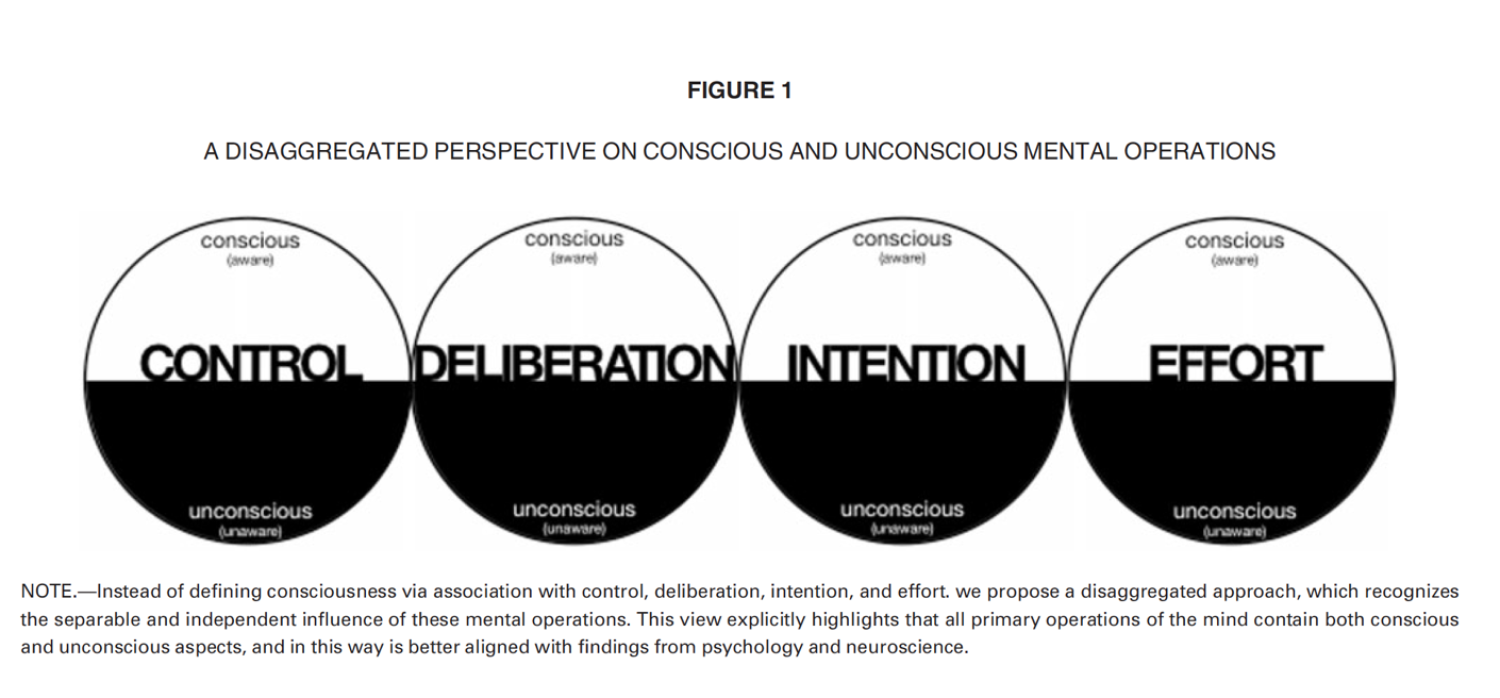

The authors argue that instead of starting by examining the conscious thoughts that consumers associate with their behavior, researchers should “consider consciousness second,” in order make sure that they take the time to identify causes of behavior that are less obvious and more difficult to measure than simply asking people about their thoughts. If “bad” consumer behavior is caused by conscious thinking, then changing that behavior can be as simple as modifying thoughts. Much public policy aimed at helping consumers make better decisions takes this tack. However, if bad behavior is caused by deeper, more bodily factors, then it could be more effective to modify those influences directly (for example, by prescribing probiotics, changing diets, and breaking habits by changing the physical surroundings that trigger habits), than simply changing what people think.

Williams, L. E., & Poehlman, T. A. (2016). Conceptualizing consciousness in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(2), 231-251.