CHIPS Ahoy? Federal Incentives No Guarantee of More U.S.-Made Semiconductors

A Leeds expert says funding, plus threats to supply chains, might make domestic manufacturing more palatable—but it’s a long, and expensive, road.

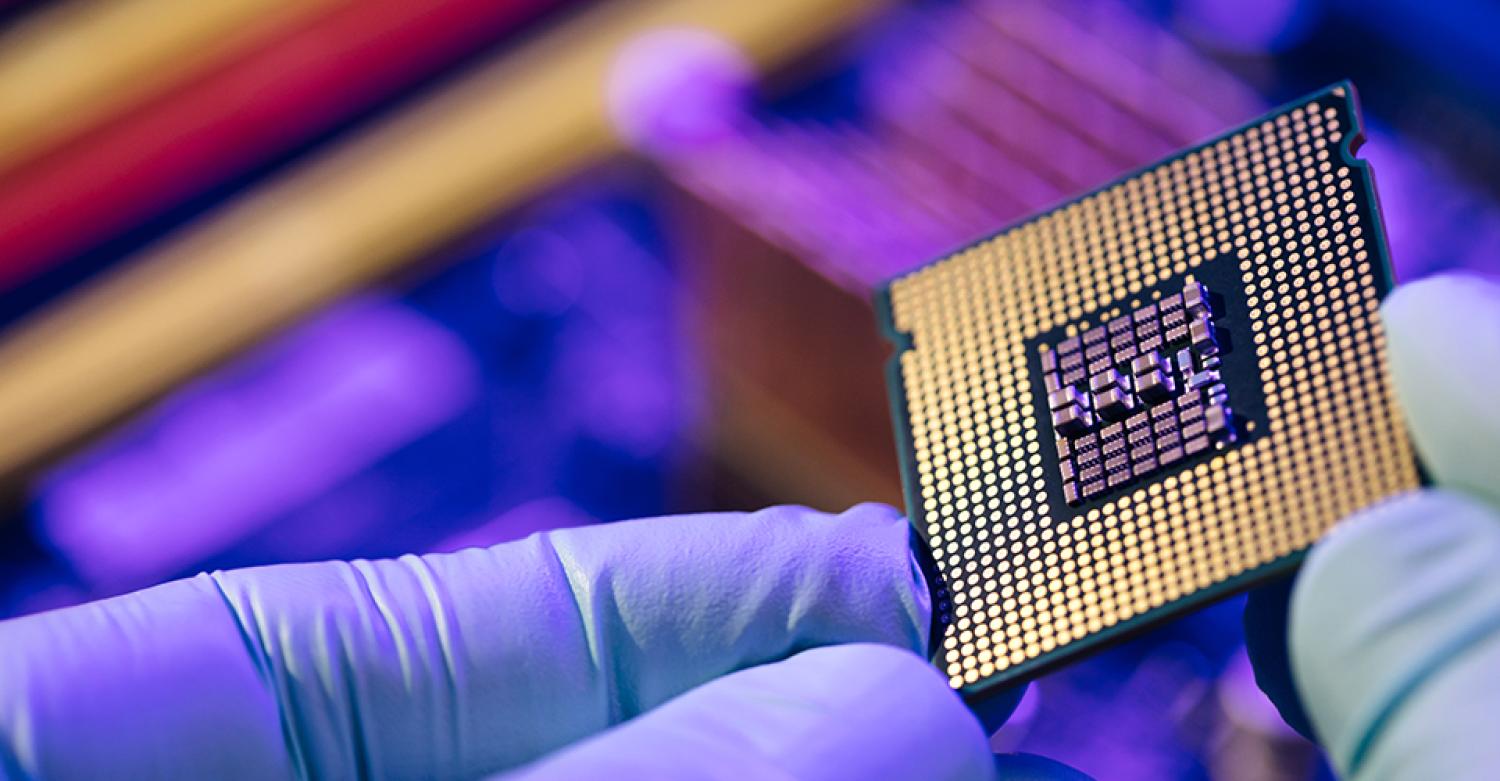

A worker examines a semiconductor chip before installing it. Federal incentives designed to spur U.S. chip manufacturing are expected to go into law this week, as companies grapple with chip shortages—and resulting cost overruns—due to the supply-chain crisis.

A $52 billion federal package to incentivize U.S. production of semiconductor chips has energized the high-tech sector, but operations experts aren’t convinced it will be the end to dramatic shortages that have created pain points throughout the supply chain.

Gurumurthi Ravishankar, faculty director of the supply chain master’s program at the Leeds School of Business, said the idea of reshoring—or moving manufacturing operations back to the United States from abroad—has gained appeal in plenty of industries, not only semiconductors.

“That kind of investment in the U.S. is not something that will happen quickly, or without significant consideration,” Ravishankar said. “It makes for good press to say you’re moving manufacturing back to the U.S., but it’s not easy to accomplish. You can’t abandon the investments and partnerships you’ve made around the world, and even when you do make an announcement, you’re still five or six years away from creating products.”

The so-called CHIPS and Science Act is designed to shore up the United States’ ability to produce semiconductors while challenging China’s dominance in this space. It would create more than $20 billion in investment tax credits for chipmakers, along with more than $10 billion for research and development. President Joe Biden is scheduled to sign the legislation into law early this week.

Domestically manufactured semiconductor chips represent about 10 percent of the global market, down from 38 percent in 1990, mostly because of the lower costs of imported chips. But the supply-chain crisis ushered in by the pandemic, as well as a worsening geopolitical climate, is changing the calculus for companies, who must consider the potential for supply disruption alongside the cheaper costs of creating chips overseas.

“That’s the premium companies have to factor in when it comes to considering a factory in the U.S.,” Ravishankar said—especially as the price for a new semiconductor fabrication plant can easily top $10 billion.

The good news, though, is that semiconductors aren’t going away anytime soon. When Biden urged oil companies to increase refinery production, the industry had a natural counter—the country is moving away from fossil fuel consumption, so why spend billions of dollars bringing new facilities online that would be short lived?

“The prerequisite for investing in a factory is knowing there is demand for a pipeline of products that will be produced there for many years to come,” Ravishankar said. “Unlike oil, semiconductor demand is steadily growing, there is no global push to get rid of them and the market is incredibly competitive.”