Natural Products Ecosystem Helps Disrupt Mature Food Company Dominance

A remarkable dynamic has unfolded in the food and beverage industry where small, disruptive brands have accounted for a disproportionate amount of overall industry growth.

This is an unusual set of circumstances wherein classic competitive strategy has failed to predict actual outcomes – large-scale, public companies with tremendous manufacturing scale, highly experienced and well-compensated executive ranks, vastly superior purchasing power, and a symbiotic relationship with the nation’s largest retailers have failed to insulate the incumbent industry leaders from the external threats posed by much smaller, modestly resourced, disruptive brands.

What are the reasons that the established, high-margin, branded food companies – with their theoretically large competitive moats and impenetrable fortress walls – have defied classic competitive strategy by failing to keep small, less well-resourced competitors at bay? And what can explain the capitulation – whereby these dominant players pay unprecedented premiums to acquire their often-diminutive and disruptive competitors?

Macro Trends

1. In the 40+ years since the original natural and organic food companies got their scrappy and entrepreneurial start (Whole Foods was founded in 1980), a quiet but steady following has grown for wholesome, nutritionally dense, and clean-label foods.

2. Meanwhile, the commercialization of genetically modified food ingredients has dominated the increasingly monocultural agricultural supply chain (notably corn and soy), making food both plentiful and inexpensive.

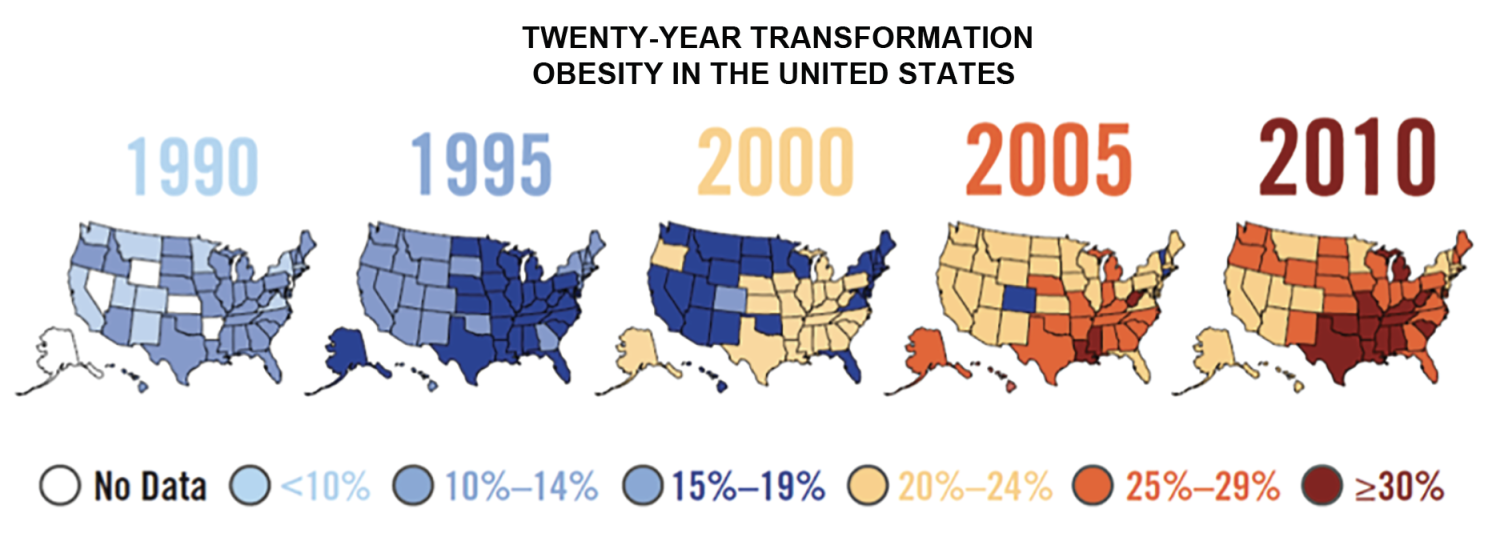

3. A somewhat simultaneous (yet gradual) public health crisis has developed as America has continued down the path of weight gain and obesity. This phenomenon has certainly reflected and highlighted our mainstream dietary choices (See CDC obesity data on page 1).

4. Rightly or wrongly, “big” has increasingly been affiliated with “bad” – be that big government, big banks, big pharma, or big food

and ag.

5. As the rate of change in technology and culture has increased, disruptive business models have dislodged incumbent predecessors—and overall corporate lifespan has decreased.

A Natural Products Ecosystem

As many of the pioneering natural and organic food companies have gradually been acquired by large companies (Celestial Seasonings, White Wave, Horizon Organic, Stonyfield Farm, Honest Tea, to name a few), many of the founding entrepreneurs have reinvested capital proceeds and hard-won experience to mentor and grow the next generation of natural and organic brands and companies. Nowhere is this dynamic more apparent than in Boulder, Colorado. A virtuous cycle has emerged – fueled by abundant equity capital, inexpensive debt, an increasingly rich talent marketplace, and a culture of collaboration.

As leading incumbent food and beverage companies continue to look externally for growth and disruptive innovations, this dynamic has deepened and accelerated. With resources resulting from successful exits at handsome valuations, many natural and organic brand champions and company leaders have formed their own angel investor networks, venture capital firms, and private equity funds. In Boulder, a few examples include Sunrise Strategic Partners, BIGR, Boulder Food Group, CAVU Venture Partners, Sonoma Brands, Powerplant Ventures (several of these are shown on the investor landscape graphic on page 16).

This has occurred as established incumbents formed their own corporate venture capital groups to fund participation in this entrepreneurial ecosystem. A highly successful initial public offering by Annie’s Homegrown in 2012, followed by their acquisition in 2014 by General Mills, set a new high-water mark for valuations and enthusiasm in the natural and organic sector. (General Mills paid $825M for Annie’s – then with about $200M in sales and only modest profitability).

Innumerable high-growth natural and organic brands have subsequently enjoyed financially lucrative sales to incumbent consumer product company leaders, further fueling investment in disruptive start-up brands.

Growth vs. Profitability

A rather pronounced polarity first emerged in the food and beverage space in 2012-2013. About one year after General Mills acquired the high-growth Annie’s Homegrown company, the Brazilian private equity group 3G Capital teamed up with Berkshire Hathaway to acquire the H.J. Heinz Corporation. In 2015, they added Kraft foods in a mega-merger to create Kraft-Heinz, which became a public company. 3G laid-off more than 7,000 employees in the combined companies – including many senior executives – and closed many factories. This cost cutting enabled a significant near-term boost in earnings-per-share. Wall Street loved their early results and richly valued the company, and by extension, their approach of radical cost-cutting. As Kraft-Heinz became a darling of Wall Street, their public company peers quickly emulated the priority of cost-cutting – and in many cases emulated 3G’s utilization of zero-based budgeting (ZBB).

While many functions suffered in this radical cost-cutting, none suffered more than longer-term initiatives in research and development and in marketing. At the same time, layers of senior management throughout the industry were also cut. Over time, the virtues of short-term cost-cutting proved very damaging in the long term as growth in core categories was either negative or neutral. And the innovation engines (R&D and Marketing) had been decimated in the process.

On the other end of this polarity spectrum, venture capital and private equity investors prized high growth at virtually any cost in an increasingly winner-take-all paradigm.

As impressive acquisition valuations continued to dot the food and beverage landscape, more and more investment capital flowed into the sector in search

of high-growth products and brands. The acquisition logic was rather simple: Brand X has demonstrated great consumer appeal and high growth despite marginal profitability. When we plug this into our supply chain and manufacturing capacity, we can fix the margin structure and profitability.

While this logic proved to be only occasionally true, ample rewards for investors and entrepreneurs have sustained the virtuous cycle supporting disruptive challenger brands and an ever more robust ecosystem of investment capital, entrepreneurial consumer insight, operational expertise, and the ability to scale companies beyond the proof-of-concept stage.

In some cases and sectors, the growth-at-any-cost paradigm has led to unwarranted investment. Many spectacular failures in the meal kit space proved that costly customer acquisition and larger volumes cannot fix underlying economic flaws. While not as spectacular as examples such as WeWork and Casper, the growth-at-any-cost model is generally giving way to a more disciplined proof of concept and economic viability approach.

Global Pandemic: Consequences and Implications

The tremendous shock to both U.S. and global economies has been as extreme as it has been sudden. Consumer staples, while unsexy, have performed exceptionally well in our current stay-at-home environment as caloric consumption in the United States is largely inelastic. While recent history has shown that the foodservice market (away-from-home consumption) is equal in size to total grocery sales (for in-home consumption), the current circumstances naturally confer a significant advantage, for the time being, to grocery sales. As well, legacy brands have bounced and regained some market share during the crisis, benefiting from established supply chains, excess manufacturing capacity, and the out-of-stock situation that many disruptor brands have experienced.

The restaurant sector faces existential challenges as long as distancing norms keep the economy partially shuttered, but food and beverage as a whole are guaranteed to grow at least at the rate of population growth. While outsized growth will continue to be rewarded in the marketplace, healthy growth requirements only slightly exceed population growth

(1-2%). For now, at least, the growth-at-any-cost model will be displaced by a highly disciplined cost and cash management perspective.

What is also likely to endure is the lush investment ecosystem enjoyed by the natural products industry where there has never been a better time for disruptive entrepreneurs to access the resources, talent, mentoring, and the cooperative networking needed to win.

John Grubb is Managing Partner at Summit Venture Management. He may be reached at john@summitventuremanagement.com.

Please contact me directly at 303-492-1147 with any comments or questions.

-Richard Wobbekind