Uncovering What Was Always There: Black History at Colorado Law

As some institutions retreat from efforts to lift marginalized voices, it is more essential than ever that we continue the work of recovering our past. This project is about pursuing a whole understanding of our institution’s past, making this essential part of our shared historic tapestry visible. Recognizing the contributions of our Black students and alumni enriches our institution and illuminates the path forward in our ongoing pursuit of excellence. We do this work because we can, and because we must.

While this project focuses on the University of Colorado Law School, it reflects a broader reality: the histories of Black students, faculty, and staff have too often remained hidden at law schools across the country.

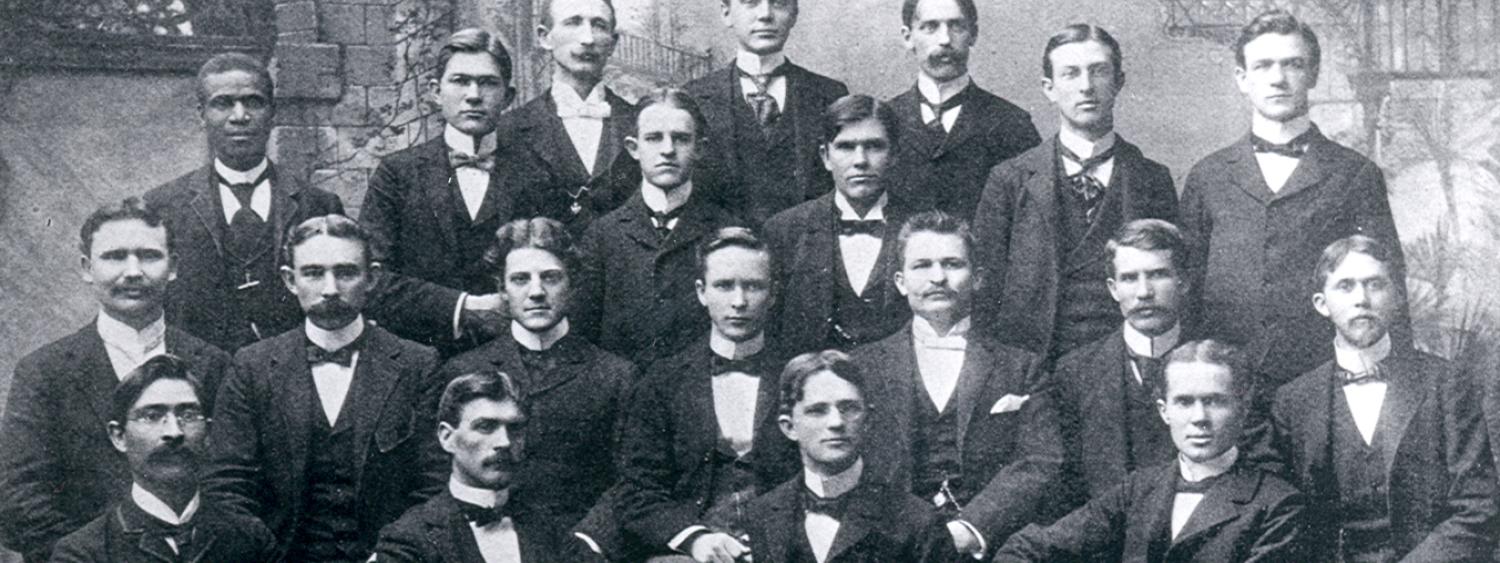

This research restores these individuals to the narrative of Colorado Law after, for some, more than a century of erasure. Franklin LaVeale Anderson (ex. 1899), Colorado Law’s first Black student in 1899—whose image, long mislabeled, hung in a dark corner of the library—is now remembered as a successful Boulder businessman and landowner. Franklin Henry Bryant (1907), the law school’s first known Black graduate, appears only briefly in a 1909 yearbook but emerges through research as a poet with training in both medicine and law. Adele “Della” Parker (ex. 1914), the first Black woman law student, known only through newspaper clippings and yearbooks, was a gifted orator and dedicated educator. And alumni from the 1940s—Arthur Erthal Green (1945) and Isaac Edward Moore Jr. (1949)—are recognized for their significant contributions to civil rights advocacy in Colorado and California. These stories are not footnotes; they are foundations.

Franklin LaVeale Anderson (ex. 1899), Colorado Law's first Black student, pictured on far left.

A Barber Goes to Law School: 1892 – 1899

“Owing to a considerable demand for a Law School in the Rocky Mountain region,” the University of Colorado Board of Regents opened a law school at CU in 1892. Neither the university nor the law school had a racial or ethnic discrimination policy, which enabled Franklin LaVeale Anderson to enroll in 1896 as Colorado Law’s first Black student. His story and those of several other early Black law students who attended Colorado Law can be found at colorado.edu/law/BlackHistory.

More than a century later, Anderson’s law school career still inspires students and alumni. Reflecting on 130 years of the law school’s history, Ryan Haygood '01 spoke of Anderson’s image in the 1899 class photo:

"I cannot imagine what Mr. Anderson endured, the hostility he confronted, or the racism he battled, and I drew inspiration from Mr. Anderson’s 1899 class photo every day as I walked past it in the law school... I’d like to think we [Haygood, Lisa Calderón '01, and Joi Williams '01] were then—and are now, 20 years into my practice as a lawyer—walking in his footsteps. Mr. Anderson has been an example to me both of what is possible and what is required of us now. And for inspiring us to use our law degrees to fight for it.”

The Poet and the Rhetorician: 1900 – 1940

During the early 20th century, the nearby city of Denver was seen as a profitable place for Black attorneys to establish their practices. This likely attracted Colorado Law’s first Black graduate, Franklin Henry Bryant (1907)—a poet educated in medicine and law and the first and youngest Black attorney to argue a case (Graeb v. Board of Medical Examiners) before the Colorado Supreme Court—and the first Black female student, Adele "Della" Parker (ex 1914), to enroll.

After Parker’s departure, records show no other Black students attending Colorado Law for more than 30 years. Several factors might have accounted for this, including the First World War. However, the political landscape in Boulder likely had a larger impact. Though Colorado laws prohibited denying access to “public accommodations” due to race by 1908, de facto Jim Crow segregation persisted. In the late 1910s and early 1920s, the city bought or seized the homes of Black residents, demolishing them to make a public park.

Shortly after, the Ku Klux Klan gained political and cultural power before national scandals lost the Klan influence nationally and in Boulder. Then, from 1929 to 1939, the Great Depression left nearly half of Black working-age adults unemployed by 1932, leaving many without the fiscal resources for graduate education. New Deal policies had varied impacts for Black Americans.

Separate and Unequal: 1940 – 1959

The 1940s and 1950s brought a significant shift in law school enrollment nationally and in Boulder. During World War II, Colorado Law lost many of its faculty and students to conscription.

After the war, several civil rights cases against predominantly white law schools and the ensuing backlash from white communities deterred Black applicants from enrolling in law schools from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. This occurred even as the Association of American Law Schools implemented antidiscrimination objectives, the American Bar Association formally allowed Black lawyers to become members, and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled segregation in educational institutions unconstitutional.

In Boulder, Black residents faced discrimination in many settings, including at CU, where Black students faced a lack of housing and social and recreational opportunities; with some noting that the white students “act[ed] superior.” Black students were confined to live in boarding houses at the town’s edge and were barred from most of Boulder’s shops, stores and restaurants in town.

White students refused to share housing with their Black classmates, and the university asked Black and other marginalized students to "live with their people.” One Black Colorado Law student, Isaac Edward Moore '49, was effectively forced off campus and faced housing discrimination in the town of Boulder; Moore ended up sleeping in a coal shed while attending law school.

Colorado Law likely admitted five Black students during the 1940s and 1950s: Arthur Erthal Green '45, who founded the New Frontier Democratic Club in California; Isaac Edward Moore, Jr. '49, who later became a Colorado representative; Clarence Edward Blair '56, who served as the city attorney for Compton, California; and two unidentified men in 1946 and 1948.

Pushing for Change: 1960 – 1979

During the 1960s, very few Black students attended CU. The sole Black faculty member, English professor Charles Nilon, estimated that 50–60 Black students in total attended CU during the early 1960s. Records indicate Patrick H. Butler '61, an attorney for Eli Lilly and Company for 25 years, and Penfield Wallace Tate II '68, Boulder’s first and only Black mayor, graduated from Colorado Law.

After the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., CU Boulder implemented its first affirmative action program, the Educational Opportunity Programs (EOP). Multiple versions of the EOP's origins exist and should be considered, including narratives that center Black law students Tate and W. Harold “Sonny” Flowers, Jr. '71. In 1970, graduates included the Hon. Gary Jackson '70, a retired senior judge for Denver County Court, and James "Jim" Cotton '70, who went on to work for IBM’s legal department.

Following them were Flowers, a Boulder attorney who established CU Boulder’s Black Alumni Association and endowed a scholarship for students of color; Alfred Tate '71, who founded the civil rights firm Tate & Renner; Clayton Adams '71, who was the vice president of community engagement for State Farm; Carol Lievers '72, who served for 24 years as first assistant attorney general for the state of Colorado; and Theodore "Ted" Woods '73, one of CU‘s first Black athletes who went on to work as a corporate attorney for U.S. West Communications.

During the first half of the 1970s, Colorado Law’s administration made efforts to recruit students from diverse backgrounds. Jackson recalls “going on recruitment trips ... trying to encourage diverse students, students of color, to come to Colorado.”

Black law students worked to establish a community, founding a chapter of the Black Law Students Association (BLSA) at Colorado Law. An early member of the BLSA, Lievers said the purpose was “bring[ing] our legal training to bear upon some of the problems, legal and nonlegal, in the Black community.” In the mid-1970s, Colorado Law faced pressure from students and the Sam Cary Bar Association to diversify its faculty. Colorado Law hired its first woman professor, Marianne "Mimi" Wesson, in 1976 and its first permanent Black professor, David Hill, in 1977.

From 1972 through 1979, Colorado Law graduated more than 20 Black students, including Frederick Charleston '72, who had a notable career as an attorney for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission; the Hon. Larry Naves '74, a former district court judge for Colorado’s 2nd Judicial District; Hon. Robert "Beau" Patterson '74, the first Black appointee to serve as presiding judge of the Denver County Court; Wallace "Wally" Wortham '74, former Denver city attorney; and Charles L. Casteel '75, senior of counsel for Davis Graham. These alumni and others contributed to an increasingly representative law school, where 12-13% of the students were students of color by 1978.

Pictured, left to right: Hon. Larry Naves '74, W. Harold "Sonny" Flowers Jr. '71, James Cotton '70, Penfield Tate II '68, David Hill, Hon. Gary Jackson '70, and Tate Alfred '71.

Making Strides: 1980 – 1999

From 1980 to 1985, Dean Betsy Levin—the first woman dean of Colorado Law—attracted “nationally prominent practitioners” to teach and lecture at the law school. Enrollment of students of color in CU’s graduate programs, including the law school, grew by 65% in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Several notable Black alumni attended and graduated during this prestigious period in Colorado Law’s history, including the Hon. Claudia Jordan '80, the first Black legal analyst at the Colorado Legislative Council and the first Black woman judge in the Rocky Mountain region; Velveta Golightly-Howell '81, who served as the director of the Office of Civil Rights at the Environmental Protection Agency; Henry Cooper III '87, a prosecutor in the Denver District Attorney’s Office; and the Hon. William D. Robbins '87, a judge in Colorado’s 2nd Judicial District.

Dean Gene Nichol highlighted the law school’s racial diversity during the early 1990s: 25% of students were students of color. In 1996, Colorado Law hired its first permanent Black woman faculty member, Juliet Gilbert, to teach the immigration law clinic. Almost 40 Black students graduated from Colorado Law during the 1990s, including Shirley Wilson Durham '92, a public defender; Vance Knapp '94, a partner at FisherPhillips; and Yvette Lewis-Molock '98, assistant general counsel for Xcel Energy.

New Milestones: 2000 – 2019

Records concerning Colorado Law’s Black students from 2000 – 2015 are limited. Several esteemed Black faculty and staff joined the school during this time: Professors Ahmed White and Dayna Matthew joined the faculty in 2000 and 2003, respectively, and in 2011, the law school hired SuSaNi Harris as its first senior director for diversity and inclusive excellence. During the latter half of the 2010s, students pushed for a more representative student body, and in 2017, the law school welcomed its most diverse incoming class to date. However, Black student enrollment remained comparatively low. On average, each incoming class between 2004 and 2019 included five Black students.

Many accomplished Black attorneys and legal experts graduated during those two decades. This includes but is not limited to Janea Scott '00, who served as senior counsel in the Land and Minerals Management Division of the Department of the Interior; Lisa Calderón '01, executive director for the Denver-based nonprofit Emerge Colorado; Ryan Haygood '01, CEO of the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice; Thomas Benson Martin '03, who worked at the 9-11 Victim Compensation Fund at PriceWaterhouseCoopers; the Hon. Nikea Bland '05, a district court judge in Colorado's 2nd Judicial District; Joseph Neguse '09, a former CU regent and a U.S. representative for Colorado's 2nd congressional district and Colorado’s first Black member of Congress; Hiwot Covell '09, senior assistant attorney general at the Colorado Attorney General's Office; Jackline Nyaga '12, dean of the Riara Law School in Nairobi, Kenya; Kira Robinson '12, a vice president at Goldman Sachs; Nneka C. Obiokoye '17, a partner at Holland & Knight; and Dardoh Skinner '18, who works in trademark enforcement.

Looking Forward: 2020 and Beyond

So far, the 2020s have presented profound challenges and opportunities for Colorado Law. During an alumni roundtable in 2022 to commemorate Colorado Law’s 130th anniversary, Lindsey Floyd '21, a staff attorney at the ACLU of Colorado, noted the extraordinary impact of the Black Lives Matter movement in summer 2020 on the law school community and its commitment to racial justice: “[T]he entire fabric of the law school changed in response to the protests in 2020. We’ve created more affinity groups, like the Council for Racial Justice and Equity and the Women of Color Collective. Professors who had never had a racial justice component to their syllabus added discussions and readings about the ways in which their subjects of law were not isolated from racism,” she said.

Former Dean S. James Anaya committed himself and the law school to confronting racism and to making advancements in the representation and welcoming of Black people at the law school and within the larger legal profession.

In fall 2020, Colorado Law welcomed its most racially and ethnically diverse incoming class, which included five Black students. In 2021, Colorado Law named its first Black dean, Lolita Buckner Inniss, and that fall, welcomed eight Black students – the most in an incoming class in 14 years. Dean Inniss has heightened the excellence and diversity of the student body and filled critical instructional needs by hiring one of the largest and most accomplished cohorts of new faculty in school history. In 2023, the law school named its first Black director of the Wise Law Library, Shamika Dalton.

The Black Law Student Association continues to be active at Colorado Law, with around 20 members.

Co-president Armania Heckenmueller '27 reflected:

“The Black community at Colorado Law may be small, but it’s incredibly strong. Whether I’m close friends with someone or just recognize a familiar face, there’s a deep sense of support and solidarity. That said, in my class of nearly 190 students, there are only six Black students. With law school applications rising nationwide, I’m hopeful that future classes will reflect greater diversity and a stronger representation of Black students.”

Heckenmueller also noted a desire to strengthen relationships among Black attorneys beyond the walls of CU.

While we are proud of the progress made—from breaking racial barriers to fostering a community where everyone matters and all can thrive—we also recognize that the work is far from over. The experiences of our early Black students and alumni underscore the need for lasting efforts to ensure that all students have equitable access to opportunities, that the diversity of the student body and faculty reflects the broader society, and that every individual feels valued, supported, and included. Colorado Law remains committed to learning from its past while actively working toward a more just and inclusive future.

The author used many sources in writing this piece. To see a complete list of sources, please visit colorado.edu/law/HistorySources.

The author would like to thank Mona Lambrecht, interim director and curator of history & collections at the CU Heritage Center, and David Hays, archivist at the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries, for their assistance with this research.

We invite readers in possession of relevant historical information or narrative to partner in this vital effort. Contact the research team at law-communications@colorado.edu.