The Sam Cary Bar Association: Colorado’s Vanguard for Black Attorneys

Author: Hon. Gary Jackson ’70

In the spring of 1971, seven young attorneys met in a Denver office and embarked on a singular mission: to advance equal opportunities for Black lawyers and judges.

It is almost commonplace today to see Black prosecutors carrying the torch of democracy and fulfilling the American principle that the rule of law should apply to all people equally. Former Vice President Kamala Harris as San Francisco District Attorney; Alvin Bragg, New York County District Attorney; Fani Willis, District Attorney of Fulton County, Georgia; and Jerry Blackwell, former Minnesota prosecutor in the George Floyd murder trial are all Black prosecutors who gained nationwide media attention in prosecuting celebrity defendants for criminal conduct.

But even in the not-so-distant past, things were so very different.

I graduated from the University of Colorado Law School (CU Law) in 1970. At that time, the nation was divided over the Vietnam War (among other issues), with student protests at Kent State, Jackson State, the University of California at Berkeley, and various other colleges and universities across the nation. The country was still reeling from the untimely deaths of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and presidential candidate Robert Kennedy. The Black Power movement was impacting all aspects of my life. In the legal arena, the death penalty had been declared unconstitutional in the case Furman v. Georgia by the US Supreme Court. The Hon. Thurgood Marshall was the Black Supreme Court justice we had revered since his selection in 1967, when Jim Cotton, Sonny Flowers, and I were admitted to CU Law. Edward Brooks of Massachusetts was the first Black US senator since the Reconstruction years. Shirley Chisholm of New York was the first Black person to run for president of the United States.

In 1970, when I was hired as a deputy Denver district attorney, I was the only Black deputy DA in the state of Colorado. There was one Latino deputy DA—Roy Martinez—but there were no Asian Americans and only four women who held the office: Anne Gorsuch, mother of current US Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch; Ann Allott, sister-in-law of Gordon Allott, a former US senator; Marilyn Wilde; and Orrelle Weeks, who later became our first Denver Juvenile Court woman judge. All four women were siloed into the non-support section of the office, collecting child support payments or practicing law in the juvenile section.

My “welcome” to the Bar of Colorado was a 1969 photograph in The Denver Post with Art Bosworth, David Fisher, and Bob Swanson. We had been hired as legal interns by Mike McKevitt, Denver District Attorney. Each of us wore a suit and tie. The only difference in our appearance was the three-inch afro on my head, the goatee on my chin, and, of course, my skin color. The photograph set off a firestorm of anonymous letters and even a negative editorial comment by a Colorado Supreme Court justice who called my appearance a disgrace to CU Law and the Denver District Attorney’s Office. My moment of celebration for the achievement of academic success initiated me immediately into the resistance that lawyers of color have faced ever since we entered the profession of law and the American Bar Association in 1925.

A gathering of District Attorney's office alumni in 1982. The photograph was taken on the steps of the old District Attorney Building on Speer Blvd and Colfax. At least 10 members of that staff became County, District, and Presiding Disciplinary judges.

Courtesy of Gary M. Jackson

Filling the Need for an Affinity Association

Sometime in the spring of 1971, Billy Lewis called a meeting at his office on 1839 York Street, inviting six other Black attorneys. Lewis, a graduate of Denver’s Manual High School and the first Black scholarship basketball player for the University of Colorado in 1956, was a graduate of Howard University, the historic Black law school in Washington, DC. He had an integrated law firm with Black partners Morris Cole and Phil Jones and white partners Natalie and Hank Ellwood. The other six lawyers who attended the meeting were King Trimble, Raymond Dean Jones, Daniel Muse, Norm Early, Phil Jones, and me.

There were a total of fifteen Black lawyers in the state of Colorado at the time, two of whom were judges. Hon. James C. Flanigan, Denver district judge, was appointed as the first Black judge in 1957 on the Denver Municipal Court bench. Ten long years after Jackie Robinson broke the color line for Blacks in baseball in 1947, Judge Gilbert Alexander was the other Black judge in Colorado.

At that meeting, we decided to create a bar association focusing on the needs of Black attorneys and the issues of our Black community. The organization would be a local one but in the mold of the National Bar Association (NBA), the nation’s oldest and largest national network of predominantly Black attorneys and judges. The NBA was established in 1925 at the convention of the Iowa Colored Bar Association. On August 1, the NBA incorporated in Des Moines, Iowa, as the “Negro Bar Association” after several Black lawyers were denied membership in the American Bar Association. When the number of African American lawyers barely exceeded 1,000 nationwide, the NBA tried to establish “free legal clinics in all cities with a colored population of 5,000 or more.” Its members supported litigation that achieved a US Supreme Court ruling that defendants in criminal cases had to be provided with legal counsel. Members of the NBA were leaders of the pro-bono movement at a time when they could least afford to provide legal services for free. When the Supreme Court outlawed school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education, the NBA was only nineteen years old.

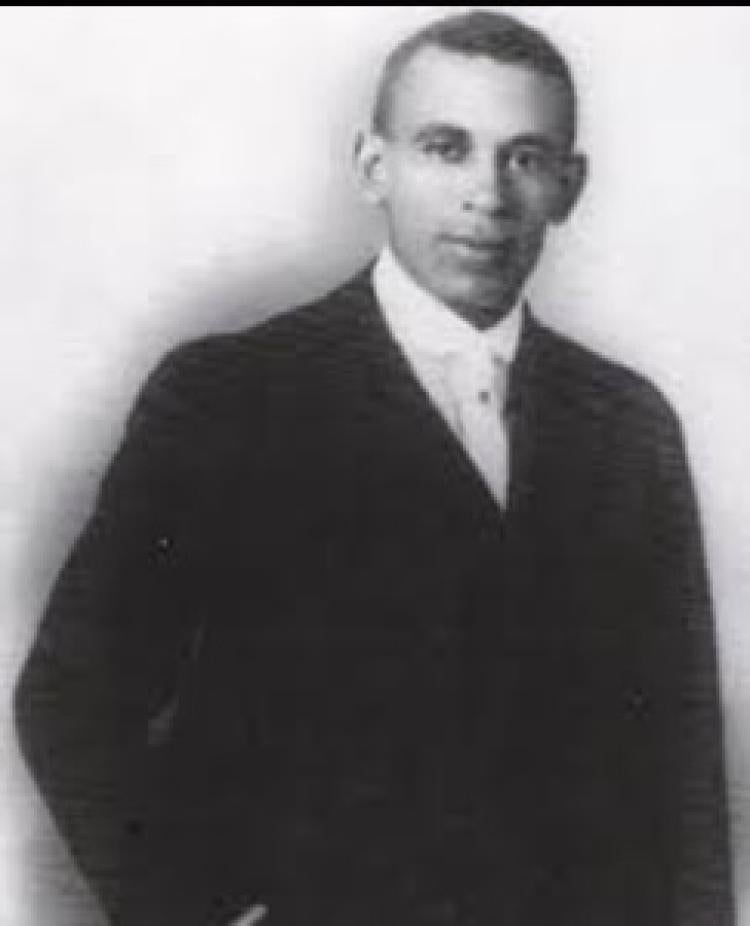

In Colorado, we named our organization the Sam Cary Bar Association (SCBA) after one of Colorado’s first prominent Black lawyers: Samuel Eddy Cary, who had a solo practice in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood. Born in 1886 in Providence, Kentucky, Cary was the first Black graduate of Washburn University School of Law in Topeka, Kansas. Admitted to the Colorado Bar in October 1919, he was known for his outstanding trial abilities and for defending the rights of Black, Brown, and poor people. At the time, he was the only Black attorney practicing law in Colorado. On September 30, 1926, Sam Cary had to endure the harshest jolt of his life and career when he was disbarred by the all-white Colorado Bar Association. Exactly nine years later, on October 1, 1935, he was reinstated to the Colorado Bar; he continued practicing law until June of 1945, when he passed away as a result of throat cancer.

In 1971, the founding members of the SCBA researched the late Sam Cary’s background, including the reason for his disbarment. Founders spoke with former Colorado Chief Justice O. Otto Moore, who advised us that the disbarment was both racially and politically motivated at a time when members of the Ku Klux Klan held positions of power in state and local government, as well as in the judiciary. Thus, the SCBA took Cary’s name and became Colorado’s first minority bar association, or what is now known as a specialty or affinity bar association. We were all under thirty-five years of age, activists, community organizers, and fearless in terms of what we wanted to accomplish: equal opportunities for Black lawyers and judges. With no Black partners in the commercial law firms along Denver’s Seventeenth Street, no Black professors at the law schools, and only two Black judges and one Black deputy district attorney in all of Colorado, it was a profession in which many voices were not being heard and the economic rewards were all directed toward white men.

Samuel Eddy Cary was the first Black man to graduate from Washburn Law School in Kansas. He moved to Colorado and began practicing law here in 1919.

Courtesy of Gary M. Jackson

The Vanguard

The Sam Cary Bar Association became the vanguard organization in advancing the need for more lawyers of color and women attorneys in the state of Colorado. It was our mutual belief that forming a Black bar association was necessary for a multitude of reasons. We came together to create a bar to expand our influence—not through separation but through our need for inclusiveness and equity in the legal profession. Each of us became a leader within the legal profession. SCBA played a significant role in expanding the representation of diverse lawyers to key appointments of judgeships, committees, and associations. Importantly, four of the seven founders went on to become city, state, and federal prosecutors at various times in their careers.

Leaders of SCBA were not only local leaders but rose to national acclaim. Wiley Y. Daniel was our tenth SCBA president in 1981. He accelerated to high public profile as Colorado’s first Black federal court judge in 1995, selected by President Bill Clinton. Before his appointment to the bench, he served as the first and only Black president of the Colorado Bar Association from 1992 to 1993. Born in 1946 in Louisville, Kentucky, Daniel earned his undergraduate and law degrees from Howard University. After practicing law for seven years in Detroit, he moved to Colorado in 1977. He immediately became an active member of the SCBA. Appointed chief judge of the US District of Colorado in 2008, Judge Daniel was the president of the Federal Judges Association from May 2009 to April 2011. In 2013 he was appointed as a special mediator for the City of Detroit’s bankruptcy—the largest municipal bankruptcy at that time, involving approximately 18 billion dollars of debt. Judge Daniel, along with a panel of mediators, helped negotiate a settlement with creditors and with city employees regarding their pensions. According to the Associated Press, the settlement led to about 7 billion dollars of debt being restructured or wiped out, and to other financial relief set aside to improve city services.

Another significant case of Judge Daniel’s was Roy Smith v. Gilpin County, Colorado. This civil rights case involved extraordinary allegations of racially motivated crimes against Roy Smith, an African American man, including torture while hanging from a beam in his house, being shot at, and being assaulted with a vehicle. Among other charges, the case alleged that the Sheriff’s Department failed to investigate Smith’s complaints of ongoing racial harassment and failed to protect him based on racial animus. As The Denver Post reported on December 24, 1996, Judge Daniel stated in a hearing that the case had “the most appalling and reprehensible record I’ve ever seen.” He found that the defendants were not entitled in qualified immunity, stating that Smith “demonstrated not only a pattern of deliberate indifference on the part of the individual officers and the Sheriff’s Department, but also presented direct evidence of racial slurs that was[sic] sanctioned by the Sheriff’s Department.” Settled before trial, the case was featured in an episode of 20/20 with Barbara Walters and was the subject of a documentary screened at the Denver Film Society.

Former presidents of the Sam Cary Bar Association, from left to right, Wally Worthan, Hubert Farbes, Earle Jones, Linda Wade Hurd, William Harold Flowers, Jr., Hon. Ray Dean Jones, Hon. Gary M. Jackson and Hon. Wiley Y. Daniel.

Courtesy of Gary M. Jackson

Lastly, Judge Daniel was an extraordinary leader for the Sam Cary Bar Association. He served as chair of the Sam Cary Convention Committee in hosting the sixty-first Annual Convention of the National Bar Association in July 1986. With more than 1,500 Black lawyers and judges coming to Denver, his leadership put the SCBA on the map of the best Black bar associations in the country. Daniel passed away in May 2019.

Hon. Gregory Kellam Scott was appointed a Colorado Supreme Court justice in 1993 by Governor Roy Romer. Graduating from Rutgers in 1970, Scott earned his law degree with honors at Indiana University Law School. He started his career with the US Securities and Exchange Commission in Denver. Scott moved on to teach law at the University of Denver Law School for more than a decade. On the Colorado Supreme Court, he participated in more than 1,000 cases. Scott authored the opinion in Hill v. Thomas, a landmark case that concluded in early 2000 in which the Supreme Court upheld legislation that allowed a buffer zone around anyone entering or exiting healthcare facilities to avoid violence by picketers. During his time on the bench, Scott issued a concurring opinion in the 1994 decision of Evans v. Romer, in which the court blocked the enforcement of Amendment 2, a 1992 constitutional amendment prohibiting government protections for gays and lesbians. “Amendment 2 effectively denies the right to petition or participate in the political process by voiding…redress from discrimination,” Scott wrote. “[L]ike the right to vote which assumes the right to have one’s vote counted, the right peaceably to assemble and petition is meaningless if by law, government is powerless to act.” Scott resigned from the Supreme Court in 2000 and died on April 1, 2021.

A third leader of SCBA who gained national prominence was Norman Strickland Early Jr. Norm Early attended American University and then obtained his Juris Doctorate at the University of Illinois at Champaign. He came to Colorado in 1970 on a Reginald Heber Smith Community Lawyer Fellowship and worked for the Legal Aid Society of Metropolitan Denver. In 1972 District Attorney Dale Tooley hired Early as a deputy district attorney; he served in the position until 1983, when Governor Richard Lamm appointed him as head of the Denver District Attorney’s Office, a post he held until 1993.

Early became known nationally as a fierce advocate for the rights of victims, and he worked hard to create the most diverse district attorney’s office in the state. He helped establish and lead organizations such as the National Organization for Victim Assistance, for which he served as president. The Colorado Organization for Victim Assistance named its highest honor the “Norm Early Exemplary Leadership Award.” A champion of crime victim’s rights, Early was also co-founder of two premier organizations dedicated to ensuring the success of Black lawyers. He created an organization to unite and advance Black prosecutors in 1983—the National Black Prosecutors Association—with 100 individuals gathered at its first meeting in Chicago, and was elected its first president. In 1971 Early was one of the seven co-founders of the Sam Cary Bar Association. Norm Early passed away on May 5, 2022.

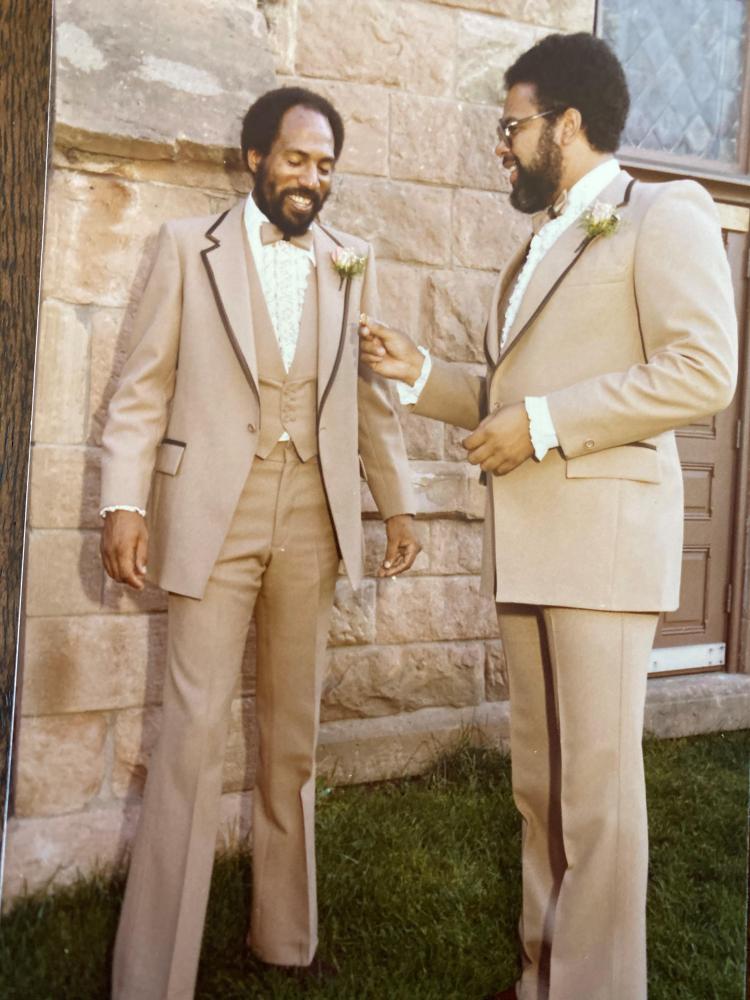

William Harold “Sonny” Flowers, Jr. and Gary M. Jackson in 1991.

Courtesy of Gary M. Jackson

Following in SCBA’s Footsteps

Other specialty bars have followed the lead of the Sam Cary Bar Association. The Colorado Hispanic Bar Association was formed in 1977 with six original incorporators. Today, there are more than 500 Latinx and Hispanic American lawyers—the largest group of attorneys of color in Colorado. The association’s ongoing mission has been to serve Colorado and promote justice by advancing Hispanic interests and issues in the legal profession while seeking equal protection for the Hispanic community before the law.

The Colorado Women’s Bar Association (CWBA) was created in 1978; its first president was Natalie Ellwood, who was employed at the Billy Lewis law firm. The Hon. Zita Weinshienk was the face of the CWBA in the 1970s. She graduated from Harvard summa cum laude in 1958, but, as a Jewish woman, she could not obtain a job with the Seventeenth Street law firms in Denver. In 1964 she became the first woman on the Denver Municipal Court; she was a Denver County Court judge from 1965 to 1971. She was appointed to the Denver District Court in 1972, and in 1979 President Jimmy Carter appointed her as the first woman on the US District Court of Colorado.

The CWBA’s mission has remained the same since its inception: to promote women in the legal profession and the interests of women generally. The founders’ vision has resulted in decades of work promoting gender equality in the legal profession, historic preservation, influencing legislation related to women and children, mentoring, granting scholarships for women law students, fighting discrimination, influencing the selection of judges, and providing training and education. Judge Weinshienk had a personal impact on my own development as a lawyer as well. Serving as her deputy district attorney in Denver County Court in 1971, I was twenty-five years old when I was assigned to her courtroom in the Denver City and County Building and was the only Black state prosecutor in Colorado. At the same time, Judge Weinshienk was the only full-time woman judge, at any level of our state and federal court systems in Colorado.

The Asian American Pacific Bar Association (APABA) was formed in 1990. Its first president, co-founder Lucy Hojo Denson, was an associate in my law firm, DiManna & Jackson, and also became president of the Women’s Bar Association in 2010. APABA is a bar association in Colorado dedicated to advancing Asian-Pacific American lawyers as leaders in the profession. It advocates for issues concerning the Asian American community and spearheads programs benefiting underserved communities, promoting civil justice, and fostering professional development, mentorship, and community.

Formed in 1993, the Colorado LGBTQ+ Bar Association (CLBA) exists to provide a sense of community and belonging for LGBTQ+ individuals in the legal field in Colorado. Through programming and other initiatives, it seeks to provide opportunities for LGBTQ+ legal professionals to interact in safe settings, build meaningful professional relationships, and enhance our members’ community and professional profiles. The CLBA has more than 350 active members and sponsors. Its first president was the Hon. Mary Celeste, a retired presiding judge from the Denver County Court. Luminaries and past presidents include the Hon. Monica Marquez of the Colorado Supreme Court’s incoming Chief Justice; the Hon. Andrew McCallan; and Jon Olofson of the Denver District Court, who has served as secretary of the Sam Cary Bar Association.

The South Asian American Bar Association (SABA) was formed in 2009. Its founder and first president, my former partner Neeti Pawar, was named to the Colorado Court of Appeals and was the first Asian American woman on an appellate court in Colorado. SABA fosters growth and advocacy of justice in the South Asian legal community, serving both the interests of the minority voices it represents and the larger community it serves through programming and community outreach.

Judge Gary M. and Regina Jackson. Judge Jackson won the Hon. Wiley Daniel Lifetime award from the Center for Legal Inclusiveness in 2020.

Courtesy of Gary M. Jackson

A Place for Specialty Associations Today

Today, with no formal barriers for diverse lawyers to become members of the American Bar Association or the Colorado Bar Association, some have questioned whether this array of affinity associations is still necessary. But I believe that the need for specialty bars is strong. Today, eighteen states have no Black state supreme court justices, and, in nineteen there are no state supreme court justices who publicly identify as a person of color.

If we reflect on the criminal prosecutions of President Donald J. Trump and of Hunter Biden, the son of former President Joe Biden, those cases raise the question of how Americans are maintaining and upholding our democratic principle that all are accountable under the rule of law. We are greatly concerned about the massacres of our children at our schools, which raise questions about the interpretation of the Second Amendment of our Constitution and its viability in a world inundated with automatic weapons. Access to the voting booth has become more restricted in some states, and people of color, women, and LGBTQ+ individuals are also underrepresented in many.

The mission of specialty bars today remains the same as always: to overcome barriers and to promote equality in the judicial system so no one, regardless of race, gender, or identity, faces discrimination under the law. Specialty bars are creating great leaders who have reached beyond their associations to make an impact on the legal profession at large, and they have a voice that needs to be heard in the major legal and constitutional questions that the people of this country must answer.

The Sam Cary Bar Association in Colorado began this movement of diverse leaders and associations, and it continues to lead the way on the path to creating a more perfect union.