Anti-Racism and Intersectionality Caucus Presents Findings in First Newsletter

As part of its work to address the need for anti-racism and intersectionality within the law school and the legal profession, the University of Colorado Law School’s Anti-Racism and Intersectionality Caucus has released its first newsletter to the law school community. Professor Deborah Cantrell developed the caucus in fall 2020 to create an ongoing space for 1Ls to converse about, experience, and practice anti-racism and intersectionality. Approximately 20 1Ls participated this academic year.

To learn more, please contact Deborah Cantrell.

The Anti-Racism Papers: Starting at Home Court

1st Edition | Spring 2021

By the Antiracism and Intersectionality Caucus

The 1L Antiracism and Intersectionality Caucus was founded as an opportunity to explore antiracism and intersectionality within the law school and legal community. Students come to this learning space to discuss racial justice and the ways in which it permeates the legal profession. In solidarity with students of color, we have fought for POC to be involved in important administrative decisions, confronted microaggressions in and out of the classroom, and advocated against participation-based grades, which often put POC at a disadvantage. While diversity and representation are important, our main goal is to dismantle white supremacy within our law school community by interrogating cultural norms and systemic inequities.

Race and ethnicity have played a foundational role in the power relations that play out in society. Luis Urrieta, Jr. & George W. Noblit, Eds., Cultural Constructions of Identity, 17 (2018). In public school settings, these power relations and underlying biases have been shown to create hostile academic environments characterized by racial microaggressions. Zeus Leonardo, Race Frameworks: A Multidimensional Theory of Racism and Education, 126 (2013). Furthermore, several students of color in the Colorado Law community have experienced race-fueled hostility in their legal education experiences. The following illustration is an example of a microaggression similar to those experienced within the Colorado Law community:

Meet Naima. She is a Moroccan-American 1L at CU Law. She is bicultural and multilingual, and she speaks Arabic among other languages. One day during a small-group peer discussion in her torts class, she brought up a connection between a concept and a term in Arabic, and her white classmate Bradley blurted out, “but we’re speaking English right now” in response to her contribution. After hearing this, Naima was less motivated to participate with her group. When returning to the main class discussion, she was subconsciously less interested in engaging with the class. As a result, she missed the substance of the remainder of the lecture, and she started dreading small-group discussions throughout the rest of the semester. Unfortunately, Naima continued to experience microaggressions within the law school setting, including one of her fellow 1Ls patronizing her over what they perceived to be the best Moroccan restaurant in Boulder. The constant tension with classmates led to added anxiety, which negatively impacted Naima’s study habits and academic performance.

Bradley (from Naima’s torts class) might have had the good intention of keeping the conversation focused on the question. He might even consider himself a good guy, even a “woke” guy. But this TIME opinion piece brings up an important perspective regarding racism against POC in the United States: “I fear, though, that the outcome is predictable: white silence, and black pain, perhaps forever, often rooted in good white people’s blindness to how they are (unwitting) agents of white supremacy, too.” Savala Trepczynzski, Black and Brown People Have Been Protesting for Centuries. It's White People Who Are Responsible for What Happens Next, TIME (2020). As Trepczynski notes, a critical mass of white people must engage in anti-racism work in order to undo generations worth of damage. Id. If white students like Bradley start to practice anti-racism at home court, i.e., within the law school community, this will be a good step in the right direction.

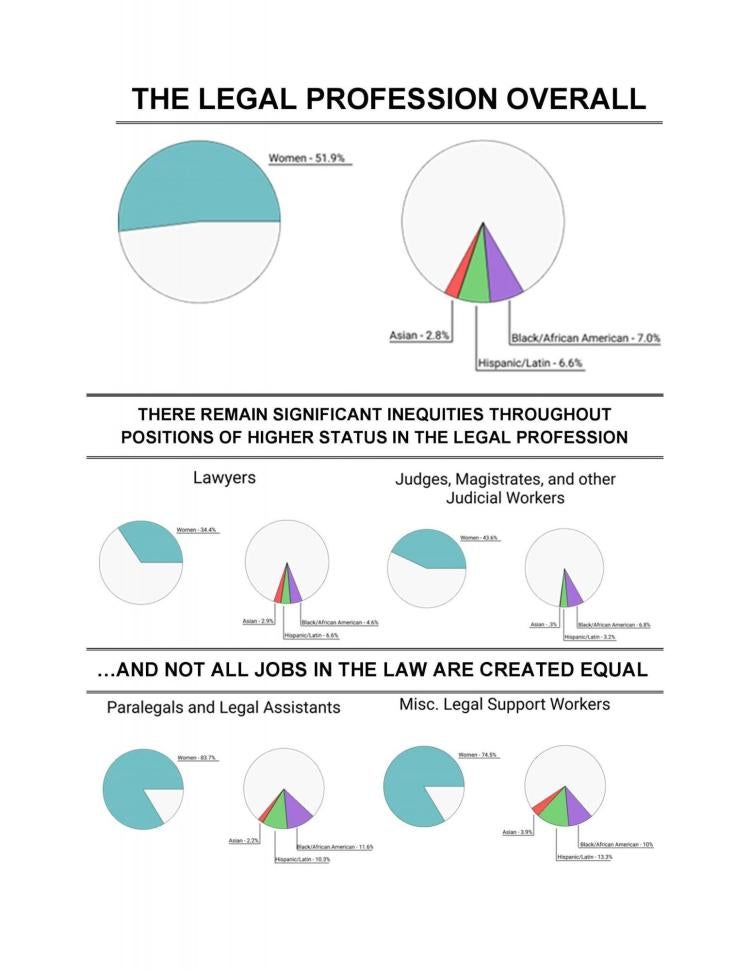

Seeing issues within the law school, the Caucus additionally sought out data regarding the treatment of lawyers of color in the broader legal community. A 2020 ABA report indicated that women of color, although comprising 14% of all associates in the country, represented less than 3.5% of partners. Furthermore, ABA data from 2008 found that women, African Americans, and Latinos were disproportionately overrepresented as legal assistance and legal support staff:

The community of lawyers in Colorado* is similarly dominated by men and lacks diversity. About 44% of those surveyed were women, while the majority - 53.5% - were men. Furthermore, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity is proportionally similar to that of the overall legal profession. Only about 14% of those surveyed identified in some way as a person of color, while the vast majority - almost 88% - identified as white.

Additionally, the Caucus examined similar statistics for Colorado Law. Out of the 185 students in the class of 2023, 49% of 1Ls are women - which is fortunately about on par with women in the legal profession overall and women in the population generally. 36% of the 1L class identify as students of color, which is about twice the overall percentage of POC in the broader legal profession.

* Based on a 2018 survey of over 8,000 active Colorado attorneys.

With these issues in mind, the Caucus came up with four ways to be anti-racist, starting in our home court:

- Consider Inequity in Your Own Career Aspirations: If you’re going into politics or nonprofit work or community organizing, ask yourself why? Are you part of the community you’re helping? If not, did that community ask you to help? When you help, are you taking up space by talking over marginalized peoples’ experiences? Or are you willing to listen? Reflect, and strive to uplift diverse voices.

- Voice Your Concerns: As we apply for summer job and internship opportunities, several students have noted that university-offered fellowships focused on social justice, diversity, and civil rights are insufficiently funded. As a result, students without enough financial means are effectively precluded from pursuing opportunities in these important areas. If you think this is an issue, consider voicing your support for increasing funding toward these fellowships to Dean S. James Anaya or Dean Whiting Dimock.

- Stay Informed: Engage with social justice and anti-racism advocacy groups on social media. Following former officer Derek Chauvin’s conviction for killing George Floyd with excessive force last spring, you can increase your awareness of anti-racism efforts by following social justice groups like Black Lives Matter, the ACLU, or the NAACP on your favorite social media platform. And, in light of the March 16th shooting in Georgia, which took the lives of eight people, including six Asian-American women, follow #StopAAPIHate and #StopAsianHate to expand your understanding of the rise in violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

- Stand Up For Your Classmates: If you have concerns about inequity in one of your classes, talk to your professors, the Dean or a trusted student group (such as the Antiracism Caucus, or the Council on Racial Justice and Equity) to address these issues. For extra support, bring a trusted professor or peer group to start conversations about these problems.

Sincerely,

The Antiracism and Intersectionality Caucus, Class of 2023