Uncovering a landmark segregation case

Railroad tracks bifurcating town of Alamosa, CO. Photo courtesy of History Colorado.

Educational historian helps unearth Colorado case as one of the earliest Mexican-American challenges to U.S. school segregation

Judge Martín Gonzales remembers when “the academics,” as he calls them, came poking around the Alamosa County Courthouse seeking records of a 1914 case challenging school segregation for Mexican-American children.

Gonzales and other locals from the south-central Colorado county had never heard of the case. However, Professor Gonzalo Guzmán, from Macalester College, had stumbled upon a short article from a 1914 Wyoming newspaper indicating important history had taken place in the San Luis Valley, where Mexican Americans have deep roots, and he partnered with CU Boulder Professor Rubén Donato to help unearth the case.

“Frankly, given how old it was, I was surprised we found the file,” said Gonzales, the retired district judge of Colorado’s 12th Judicial District. “The case appears to be one of the earliest Mexican American challenges to school segregation in the United States—if not the earliest.”

As a seasoned educational historian who has studied Mexican Americans’ struggle for justice in education, Donato was surprised to discover that the Francisco Maestas et al v. George Shone et al case was litigated decades before other influential cases documenting Mexican Americans’ fight against segregation in the 1930s and ‘40s.

“In contrast to the longstanding idea that education in America was the great equalizer, schools functioned differently for Mexican Americans,” Donato said. “However, Mexican immigrants, Mexican Americans, and Hispanos/as—those with deep roots to southern Colorado and northern New Mexico—resisted school segregation and were not passive victims who accepted their educational fates.”

Rubén Donato. Photo courtesy of Rubén Donato.

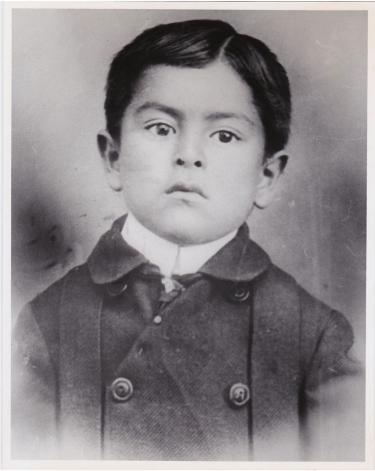

Miguel Maestas. Photo courtesy of Ronald W. Maestas.

Donato, Guzmán and CU Denver’s Jarrod Hanson studied court records and newspaper accounts to document how Mexican-American children’s racial background and linguistic needs were contested in the Maestas case and how it was received.

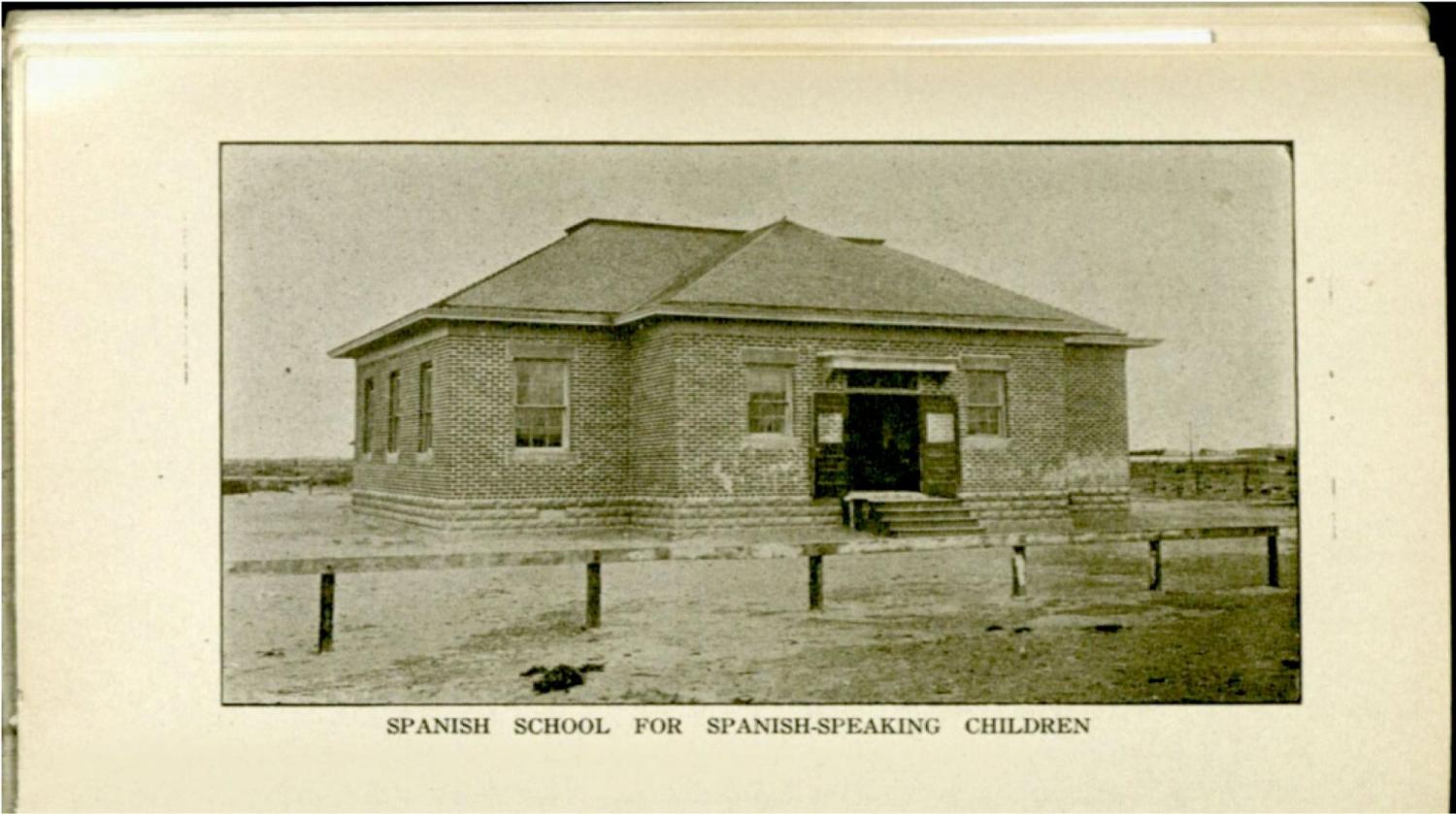

In the case, Francisco Maestas’ son, Miguel, was denied admission to the white school that was closest to their home and ordered to attend the district’s “Mexican school” across the railroad tracks. The Hispano/a community organized, boycotted and hired a Denver attorney. They maintained their children were denied admission because they were racially distinct as Mexicans, and the Colorado constitution prohibited classifying public-school children based on color and race.

The defendants—school board members and the superintendent— argued Mexican-American children were Caucasians, therefore not segregated by race, but it was appropriate to segregate non-English-speaking students in a separate school. However, officials were sending all Mexican-American children to the separate school, regardless of their English-language abilities.

Judge Charles Holbrook ruled in favor of Maestas, finding officials could not prevent English-speaking Mexican- American children from attending schools of their choice.

“Mexican Americans knew school segregation was wrong, they resisted and they contested the practice in the court,” Donato said. The case “affirms that Mexican Americans have been challenging school segregation for over a century. It was unique, complex and hotly contested at the time.”

Donato and co-authors have published journal articles and a book, The Other American Dilemma: Schools, Mexicans, and the Nature of Jim Crow (2021), about the case. Donato, Judge Gonzales, who’s now a friend, and other community leaders successfully lobbied the Colorado state legislature to formally recognize the case and the project he considers “one of the proudest moments” of his professional career.

Gonzales is a 5th generation Hispano to the San Luis Valley and successor to Judge Holbrook, and he believes this unearthed case remains important today. “Sadly, most people of the United States learn a history that does not mention or understand our Hispano heritage in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado,” he said.

“The Maestas case underscores how important education is to us, and the willingness of my gente (my people) to organize against great adversity to achieve equal education. It shows our hope, inspiration and certainty that we Hispanos are meaningful to this ever more complex society.”

A sculpture to memorialize the case at the Alamosa County Courthouse, shown here with artist Reynaldo Rivera. Photo courtesy of Reynaldo Rivera and Hope Rivera.

The “Mexican School” where Mexican-American children were routinely sent. Photo courtesy of Gonzalo Guzmán and Jarrod Hanson.

Principal investigator

Rubén Donato

Funding

The Spencer Foundation

Collaboration + support

Gonzalo Guzmán, Macalester College; Jarrod Hanson, University of Colorado Denver; Maestas Commemoration Committee

Learn more about this topic:

Overlooked for more than 100 years