Students tap into CU Boulder ecosystem to design water-purification system

When mechanical engineering senior John Figueirinhas visits his grandparents overseas, he is careful not to drink the water from the tap. In fact, depending on the region and year, statistics show that 30-70% of Americans who travel abroad experience gastrointestinal issues due to pathogens in the water.

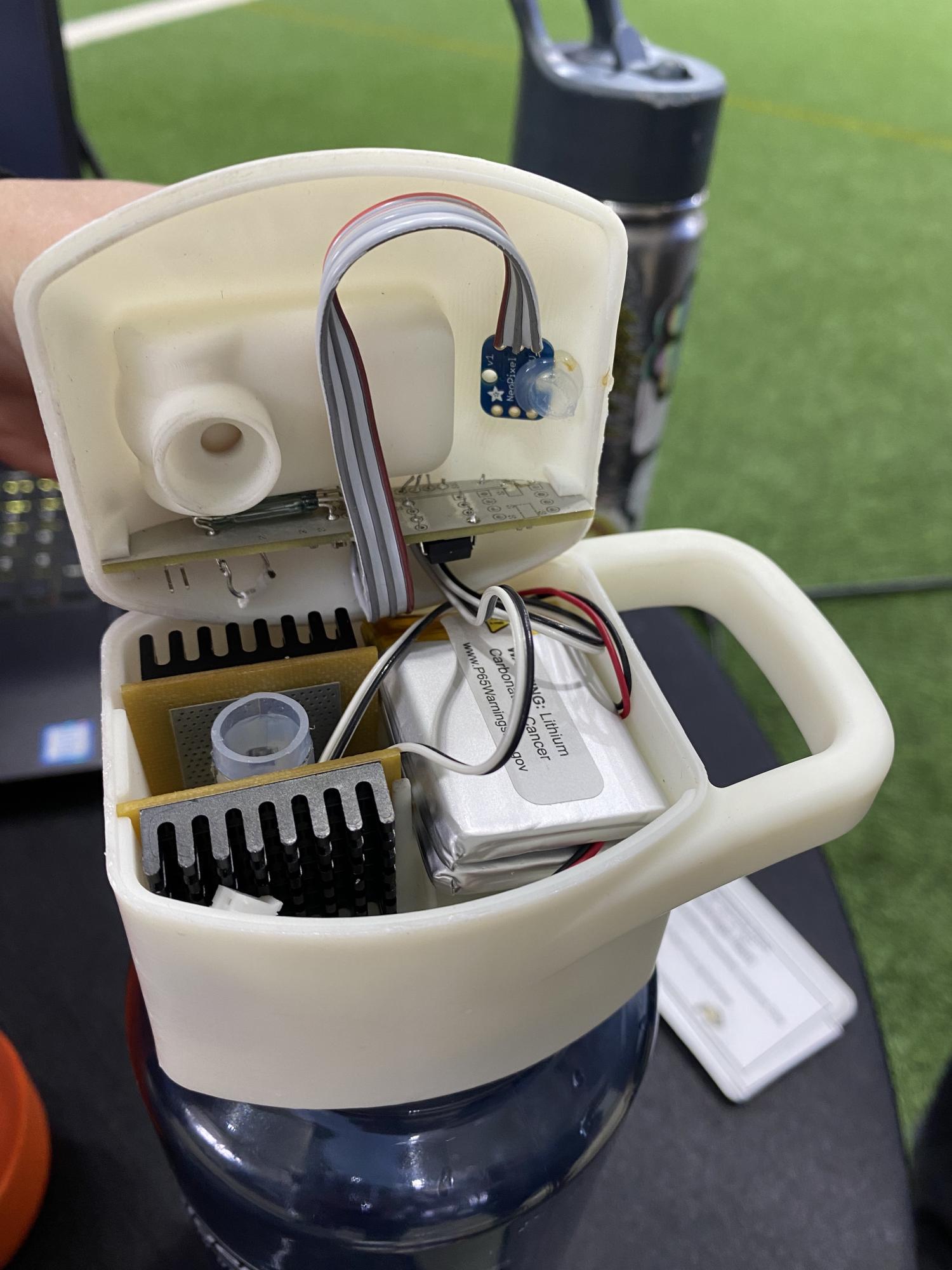

To help address this issue, a group of mechanical engineering seniors at the University of Colorado Boulder have designed a water-purification system called Puresip, which is housed inside a bottlecap and shines ultraviolet radiation through a straw to purify the water as the user drinks.

The team of students from the Paul M. Rady Department of Mechanical Engineering designed and built the prototype for their capstone senior design project.

“A key feature of our product is its adaptability,” said Project Manager Mackenzie Lamoureux. “Instead of designing a water bottle, we designed a bottlecap that can be used with most name brand water bottles like Nalgene or Hydroflask.”

One of the core challenges for the Puresip team was managing to house all the electrical circuitry, batteries and UV lights within a relatively compact design.

“We chose to go with lithium-ion polymer batteries because they’re rechargeable and have a long battery life,” said Figueirinhas, who is the logistics manager on the team. “But they’re also smaller and more compact than their counterparts.”

Figueirinhas also needed to ensure that the batteries provided the same amount of voltage and current to all the electrical components inside of the circuit, regardless of the charge, so that it would continue purifying the water at a consistent level.

To do that, Figueirinhas consulted with Jonah Spicher and Lauren Darling at the Integrated Teaching and Learning Laboratory (ITLL) Electronics Center. Together, they were able to determine what combination of voltage regulators had the correct voltage, current and size for the overall design.

A user can drink from Puresip, which turns on and begins purifying the water only when the spout of the bottlecap is flipped open, for a total of 40 minutes before the batteries need to be recharged. Assuming a user drinks at a certain pace, the team calculated that amount of time to equal 30 liters of water, or 60 disposable plastic water bottles.

“We hope that our product can help reduce plastic pollution,” said Lamoureux, “and more particularly help eliminate the need for single use plastic bottles.”

Another resource for the team was the Linden Research Group, which focuses on research related to advanced treatment technologies for water and wastewater reuse applications.

“It difficult to do a water-based project because there’s a lot of equipment you need that isn’t readily available to us,” said Testing Engineer Ella McQuaid, “so we were very thankful to the Linden Research Group for sharing their laboratory equipment and expertise with us.”

- Mackenzie Lamoureux

- Carlos Yosten

- Ella McQuaid

- Marie Resman

- Jack Isenhart

- Jack Figueirinhas

There are rigorous procedures for characterizing and testing UV LEDs when they are used for water purification. This included McQuaid testing their irradiation pattern, which characterizes the distribution of the UV light and whether it’s emitting evenly in a circle or skewed in a certain direction. She also carried out collimated beam testing, which measures the level of inactivation of bacteria when UV light is shined on a sample for a certain amount of time.

A big consideration for McQuaid and the team was making sure that the design would continue to kill 99.9% of the bacteria regardless of how fast a user would drink through the straw.

“The next phase of testing will incorporate reflective barriers in the straw,” said McQuaid, “so the irradiance gets bounced back and forth through the bacteria sample a few more times, which should increase the dose the water is getting as it gets sucked up into the straw.”

The team pitched their product Puresip at the New Venture Challenge (NVC), a cross-campus program and competition that gives aspiring entrepreneurs a chance to build a startup through events, programming, community support, mentorship and funding.

Puresip competed in the climate-focused section of the event and came in third place, with a $1,000 cash prize that help fund their project and the process of patenting Puresip, if the team decides to go in that direction after graduation.

“We got very lucky with our team,” McQuaid said. “And we got to realize a lot of what goes on at this campus by working on a project like this.”