Ongoing CU research explores impacts, solutions after Marshall Fire

On Dec. 30, 2021, a quick-moving, grass-fueled wildfire in suburban Boulder County became the costliest wildfire in Colorado history. It burned 6,000 acres, destroyed more than 1,000 homes and damaged thousands of others.

Hundreds of CU Boulder students, faculty and staff were among the thousands who fled parts of unincorporated Boulder County and the towns of Louisville and Superior that day—and the fire damaged or destroyed more than 150 homes of CU Boulder community members.

The Marshall Fire also spurred researchers—many of them personally affected by the fire—to pivot and apply their expertise to the aftermath. One year later, dozens of ongoing research projects continue to explore the science behind what happened that day, the widespread impacts on people, pets and the environment and how we can mitigate future catastrophes amid a changing climate.

Researchers Julie Korak and Cresten Mansfeldt collect surface water samples on the Coal Creek waterway.

Here's a glimpse at what they’ve learned so far, and what’s in the works.

Assessing invisible damage

For homeowners and renters in the path of the flames who did not lose their homes, a sense of relief following the fire was quickly followed by one of dread. Was it safe to go home to buildings affected by heat and smoke or covered in ash and soot?

“This brought up many questions: What chemicals are people exposed to, how safe is it to be back home and how should the homes be cleaned?” said Joost de Gouw, professor of chemistry and a Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) fellow. “Boulder County is home to the largest concentration of air quality scientists probably in the world, and many of them had directly or indirectly been affected. So it was only natural that this community sprang into action.”

De Gouw has since led a research team of engineers, social scientists and chemists across campus, and collaborated with scientists from CU Boulder, CIRES and NOAA to examine this invisible damage by measuring the quality of indoor air in affected homes and buildings.

The researchers found that shortly after the Marshall Fire, many pollutants remained at high levels inside fire-affected homes. But by early February, levels had decreased and were similar to those inside homes that weren’t affected. The researchers also tested ways in which residents could protect themselves from harmful chemicals in their damaged homes. They found that portable air filters with activated carbon provide excellent—but temporary—mitigation of indoor pollutants. The team has also reviewed the results of professional remediation efforts inside affected homes, which residents report have had varying degrees of success.

De Gouw and his fellow scientists are currently poring over their data to look for evidence of lingering pollutants that might have been derived from plastics, car tires, furniture, carpets, roofing material and other materials that burned in the fire. They’ve communicated their initial findings to Boulder County Public Health and to the general public through community meetings and social media, and will publish a portion of their official results in 2023.

Earth, water and fire

The soil and water on people’s property, in playgrounds and in public parks has also been a subject of concern since the Marshall Fire tore through these towns. Not only did homes and vehicles burn, but so did items like fabric, plastics, electronics and batteries. Their destruction likely created chemical compounds that then found their way into local soil and water systems.

Noah Fierer, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and Eve-Lyn Hinckley, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, started collecting soil samples as part of the Marshall Fire soils project, quantifying the potential for soil contamination after the fire. Almost one year later, the researchers, both CIRES fellows, are now finishing up their analyses. They are in the process of contacting homeowners with results from their individual properties and will publish their findings in the coming year.

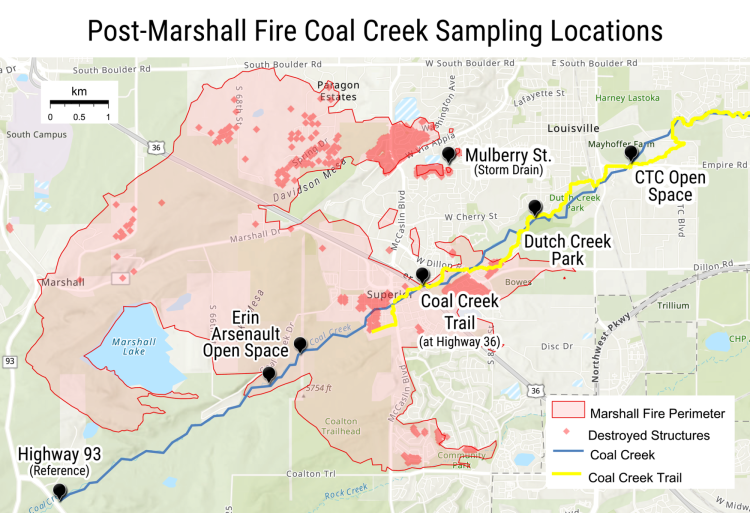

Julie Korak and Cresten Mansfeldt, assistant professors of environmental engineering, partnered with colleagues across campus, local community organizations and municipalities to collect surface water samples from the Coal Creek waterway shortly after the fire. Operating out of the back of their cars, Korak and Mansfeldt started sampling on Jan. 2, 2022, with the help of student volunteers. The work has since expanded to monitor the response of bugs and algae that live in these waters, and involve more CU Boulder faculty and students, as well as high school students.

Collaboration with local municipal governments and watershed groups like the Keep it Clean Partnership has also led to the development and release of a dashboard detailing all of the results from the campaign, which the team will update through 2023.

“From the first selection of sites to the prioritization and interpretation of monitored targets, the CU Boulder team has benefited and relied on the expertise, care and community pride of Boulder County,” said Mansfeldt.

A map depicting the locations of the surface water samples collected from the Coal Creek waterway shortly after the Marshall Fire.

Quickly converging research

The speed, coordination and sensitivity of much of this scientific response is in large part due to CONVERGE, a National Science Foundation funded collaboration established in 2018 to identify, train and support disaster researchers. Led by sociology Professor Lori Peek, this invisible infrastructure connecting the disaster research community is housed at the longstanding CU Boulder-based Natural Hazards Center, which Peek also directs.

After the Marshall Fire, CONVERGE quickly mobilized to organize several virtual forums with researchers, emergency responders, journalists, community members and representatives from municipal governments. These forums—the first of which had more than 400 registrants—jump-started the process of identifying pressing research needs, potential redundancies and ways to appropriately connect with affected communities in the immediate aftermath of the fire.

The first virtual forum also led to the establishment of the Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey, which involves dozens of researchers working together to reduce the research burden on affected communities while learning from their experiences.

“In my 20 years of being a researcher, I have never seen this kind of coordinated research effort,” Peek said.

Elise Buisson records data on grassland plants in France with a colleague

By connecting researchers to knowledge and data, CONVERGE draws on lessons that disaster researchers have learned from earthquakes, hurricanes, tornados and other calamities over decades and allows them to quickly apply those lessons in new and different ways, she said. This is critical for research in the wake of wildfires. The impact of these disasters on people is rapidly increasing, and because of climate change, the Marshall Fire may only be the start of more suburban fires this century.

“This is not something we’re done dealing with,” Peek said. “The convergence mindset and orientation to research is crucial because it asks us to consider: What are we going to do to solve that problem?”

Managing grasslands

The Marshall Fire ranks in the top 15 most destructive wildfire events in the western United States—only one of two grassland fires in that list. As the Front Range is dominated by grasslands, researchers are seeking address these ecosystems to reduce future fire catastrophes.

“Grassland fire mitigation is a new challenge for Colorado. Unfortunately, we can’t just take what we do in forests and apply that practice in grasslands,” said Katharine Suding, professor of distinction in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR).

Suding is working with the city of Boulder and Boulder County to develop ways to reduce grassland fire risk without sacrificing important benefits of grasslands, including biodiversity and soil carbon storage.

One option is virtual fencing, in which computers draw virtual fence lines, and cattle wear a GPS collar that keeps them within those invisible lines. The method targets grazing toward high-risk areas alongside neighborhoods and high fuel spots, such as ditches with overgrown grasses. As grasslands have evolved with grazing, said Suding, this approach should reduce fuels above ground but still spur growth belowground and maintain biodiversity.

Other projects include “landscape rewetting,” in which water is retained within grasslands to keep the vegetation greener and soils wetter for longer.

Engineering a better neighborhood

The drone used by CU engineers and researchers to create a detailed map of the Marshall Fire destruction.

The color of burned concrete can show researchers how hot the fire got. Photo courtesy of Brad Wham.

The effort is part of an initiative funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) called Geotechnical Extreme Events Reconnaissance (GEER), which deploys researchers to disaster sites around the world. The researchers released a report halfway through 2022 detailing their preliminary findings from the weeks and months immediately following the fire, and are continuing to analyze the data.

Other CU Boulder engineering faculty and graduate students are also in the middle of various projects, collecting data and conducting preliminary analyses on the complexities of decision-making when rebuilding post-fire.

Matthew Morris, teaching professor and fellow in the Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering, lost his house in Superior in the fire and has helped manage its design and reconstruction in the Sagamore neighborhood.

He describes this year as “an absolute grind for so many people, in so many ways.” But, he added, “people are finally getting some hope now that homes are being built in every neighborhood.”

Local stories in sharper focus

The Marshall Fire tragedy offered up an opportunity for seven journalism students in the College of Media, Communication and Information (CMCI) to hone their skills and serve the community by reporting on the aftermath of the fire.

In an immersive, newsroom-style journalism course created by teaching assistant professor of journalism Hillary Rosner and Boulder Reporting Lab publisher Stacy Feldman, the students teamed up with KUNC investigative reporter Robyn Vincent to report on experiences of survivors, the scope of loss and displacement and barriers in the recovery process.

Rosner—also a science journalist and assistant director of the Center for Environmental Journalism at CU Boulder—noted in one of the stories in the series that this reporting has brought the impacts of the Marshall Fire into sharper focus.

“Their work reflected how the Marshall Fire had functioned for the past year as a sort of living lab for the vast research community that exists in Boulder. The graduate-level journalism course aimed to explore the health impacts of the fire through the lens of this research,” wrote Rosner.

Recording community stories

In Boulder County, another team of researchers is striving to document a different kind of data before it disappears entirely: our stories.

In early 2022, the Louisville Historical Museum launched the Marshall Fire Story Project to collect and preserve stories of how the fire impacted the lives of people across the county. Kathryn Goldfarb, assistant professor of anthropology at CU Boulder, supports the effort alongside Jason Hogstad, volunteer coordinator and historian at the museum. The team now includes CU Boulder students Emily Reynolds and Lucas Rozell.

For months, the group has listened to stories about evacuating homes, lost pets and personal artwork that can never be recovered—but also the support residents received from their communities.

“We have a bag of stuff we bring with us to story sessions that includes release forms and a box of tissues,” Goldfarb said.

The Marshall Fire Story Project is funded by the Office of Outreach and Engagement at CU Boulder and is supported by the Center for Documentary and Ethnographic Media.

So far, the team is on track to record audio and video stories from around 35 people. The museum will archive the stories for use by community members, policy makers and researchers. Many survivors of the fire will spend years rebuilding their homes and lives, Hogstad said.

“Grief takes a long time,” he said. “This moment has marked these places and people forever.”