Behind the Masks: Revealing heroes in COVID-19 research

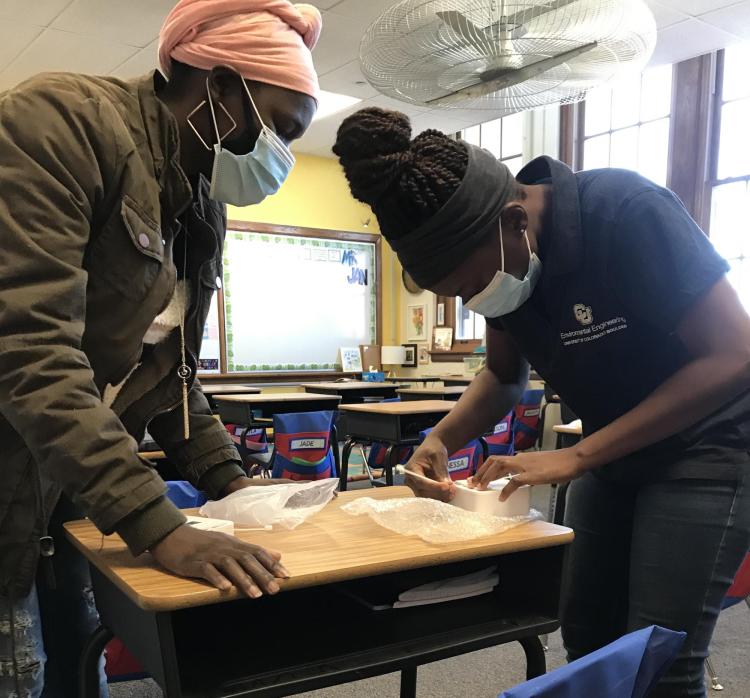

In June of this year, the University of Colorado Boulder highlighted the work that Mark Hernandez, professor in the Environmental Engineering Program at CU Boulder, and Odessa Gomez, a senior researcher in Hernandez’ group, have been doing to measure air ventilation and filtration in Denver public schools. They weren't alone in their efforts.

The lab's field technicians were all students from populations historically excluded from engineering, and who have their own dreams and ambitions for its future.

"This was no small feat for these young people, who fearlessly went into Denver metro public schools, masks and gloves on, day after day, during the heart of the pandemic," Hernandez said.

Here are the stories of four of those technicans, Halle Sago, Sylvia Akol, Jeronimo Palacios Luna and Ximena Duenas Ibarra, and what they're working for.

Halle Sago: To make walls without mold

Working in Mark's lab and doing field technician work broadened Sago's perspectives on how the built environment affects the health of students. "It's great research that I'm very appreciative to be a part of," she said.

Sago is Native American. Her mom's side of the family is Zuni Pueblo, her dad's side is Mescalero Apache, and she has wanted to pursue architecture from a young age. Though she grew up in Boulder, she frequently traveled back to her families' reservations and saw the disparities in access to quality housing.

"It hit me beginning in middle school that this is not normal. They should not have mold, or holes in the roof, and they should have access to the resources that they need for a healthy environment."

That desire became Sago's pathway to college, and everything, including the air quality research with Hernandez' team, has helped her learn more about the systems that go into building those healthy environments.

The research with Hernandez' team was a refreshing change, she said. In the program she said there were few people of color, especially instructors. She enjoyed working with folks from similar backgrounds to her own, especially people who were so positive and hard-working.

Challenges were swiftly worked through, and though there was a wide range of ages and experience levels, the group felt like a community, she said.

"While we were driving to the schools to do research, we would talk about our family and friends," Sago said.

Reflecting on her family, Sago said that through college, she has realized she never wants to take family time for granted.

"Family is a core I have, hand-in-hand with my communities. Sharing a meal and engaging in conversation is something I hold very deeply. It will always be important to me," she said.

Halle Sago (CU Boulder, EnvDes, '20); Sylvia Akol (CU Boulder, Environmental Engineering Sophomore); Ryan Carroll (CU Boulder, EnvDes, '20)

Sylvia Akol: To take a seat at the table

Environmental engineering is something Sylvia Akol has more than academic passion for.

Growing up in Kabata, a village in the Kumi District of Uganda, her village experienced significant droughts as a result of insufficient infrastructure. Though there was a nearby lake, there weren't pipes to bring water.

"There were a bunch of Europeans who came and wrote papers, but there was no solution," she said, until around two years ago when Kumi was finally able to bring clean, piped water to the village.

Akol realized that environmental engineering was an access point to providing quality, clean water everywhere, and she knew that her presence at the table where decisions are being made was essential.

"I'm confronting systemic racism… It's the only way I can be able to be part of the decisions that are made when people who look like me are not present. If I'm there, I can represent," Akol said.

Shortly after she transferred from Front Range Community College to Metro State University, she heard about Hernandez' research and became involved. The research was rewarding, Akol said, in part because of the diversity of the students the research team was serving.

“COVID really affected the Black community, the Latino community and other minority communities, and it was great to know that we were contributing part of the solution," Akol said.

When she told her family and friends about the efforts, they appreciated the care and concern the team was giving to the schools.

"It was amazing to hear how grateful they were, and to see that the kids are going to feel safer in this school where we are studying how to improve their environment,” she said

For Akol, the future is all about water. "I am resilient, strong and passionate," she said, and she will be using those strengths to bridge the infrastructure divide and provide equitable solutions everywhere.

Sylvia Akol (CU Boulder, Environmental Engineering Sophomore), Christian Sorel (Front Range Community College)

Jeronimo Palacios Luna: To reforge his path

Jeronimo Palacios Luna was excited to start working for Mark Hernandez' air-filtration research project in the spring of 2020, but at first, his family felt it was too dangerous.

"It was just barely when the pandemic was breaking out. The vaccines were uncertain; no one knew what was happening. The only thing we had were face masks," he said.

He waited until he was vaccinated, and when the team reached out to him again, Palacios was thrilled. While the job had initially meant money for college and a great research connection, he said it now held deeper meaning. During his first semester of college, all of Palacios' classes were online.

"I struggled so much. The HEPA equipment was a positive light, a piece of equipment that could help out the schools and other institutions we set them up in have a safer space to work in person," he said.

He said he also appreciated the opportunity to get out of the house and do something that felt meaningful. He was given a lot of responsibility, and with it, respect.

"We didn't have to talk that much about the work we were doing because everyone was doing it right. There wasn't really a necessity to pressure everyone or micromanage people," he said.

Having a team that was entirely people of color from diverse lived experiences was definitely fun, he said. The team often rode in the car together from Denver’s Union Station to the school they were surveying, sharing music and memes.

"You get out of your comfort zone and talk to more people. One of the first days, Sylvia told me that in Uganda, folks don't have last names. The family takes them because of globalization, but originally they didn't have last names, and I was like, ‘Oh, that's so funny because in Mexico we have three last names,’ and we were both sharing our culture and how we perceive everything," he said.

Palacios also gained more perspective on the work he was doing in school, and decided to switch majors from mechanical engineering to creative technology and design. Living in Boulder, Palacios would frequently go to Building61, the Boulder Public Library makerspace. He even presented at the 4th Annual Maker Educator Convening on "Making as a Tool of Social Justice "in San Jose, California, as a high schooler.

The pandemic broke Palacios' path, forcing him to re-examine everything he thought he knew about what he wanted to do and who he wanted to be, he said.

Now, in the light of the research he's been doing, the friends he's made, and the new opportunities ahead, he says he's reforging himself, focusing on his strengths as someone who can connect between disciplines and people.

Ximena Duenas Ibarra: To help the helpers

Ximena Duenas Ibarra is the youngest researcher on Mark Hernandez' team. Still in high school and facing her senior year, she wants to be an environmentalist to give back to the natural world, which gives so much to us.

"Think about trees. They're these real, living beings. They give to everyone, even bugs, and we're destroying them. I want to help them. I want to help the helpers," she said.

Duenas Ibarra had just gotten a job as a house cleaner when she was given the opportunity to work with Mark Hernandez' team. Duenas Ibarra decided to give it a try before deciding between the two positions and realized that she really enjoyed the research.

Everyone else on the team was older than she was, but she was held to the same standards of professionalism as everyone else. This also meant that, as a researcher, she was encouraged to ask questions and able to be herself.

"My inner Latina-ness was coming out. Usually I've had to hold it back all these years but here I was, like, ‘Wow, I can speak Spanish without having a teacher worry about what I'm saying.’ It helped me grow a lot. It shouldn't be a big deal, but it is, because you get to know yourself a little more," she said.

In a classroom, sitting and taking measurements, IDuenas Ibarra found herself wondering about many things. How did HEPA filters really work? What would happen if someone suddenly breathed a lot of carbon dioxide? She would ask another team member and often immediately get an answer.

"Sometimes people don't understand me or they don't want to answer, but this time I actually got my questions answered, which is weird. I was like, ‘Oh, I can ask questions!’" she said.

Duenas Ibarra also did her own research into the effects of carbon dioxide and found herself listening deeply to her teammates. She was relieved, she said, that she was still treated with respect, even when she was quiet. In large groups of non-Latinos, being quiet and Latina, she said people think she's dumb, but in Hernandez' team, people understood.

The work was hard, she said, requiring accuracy, accountability and consistent attention across hours of data gathering, but Duenas Ibarra was also able to see the effects of the HEPA filters. She said it was amazing how air, which flows all around us, can cause harm or help us.

At this point, Duenas Ibarra isn't sure what kind of environmentalist she wants to be, but she knows that things need to change.

"There are environmental engineers out there working to make the world safer for us, and there are people out there who don't really care, and I'm like, ‘The world is dying! We have to do something about it.’ I think that's what pushed me to be an environmentalist. We're not going to be here long if you keep doing this!" she said.

When asked what she wanted people to know about her, Duenas Ibarra was quiet before giving her answer, "I'm a Latina and yes, I did the work right," she said.