Researchers fight COVID-19 with new air filtration in Denver Public Schools

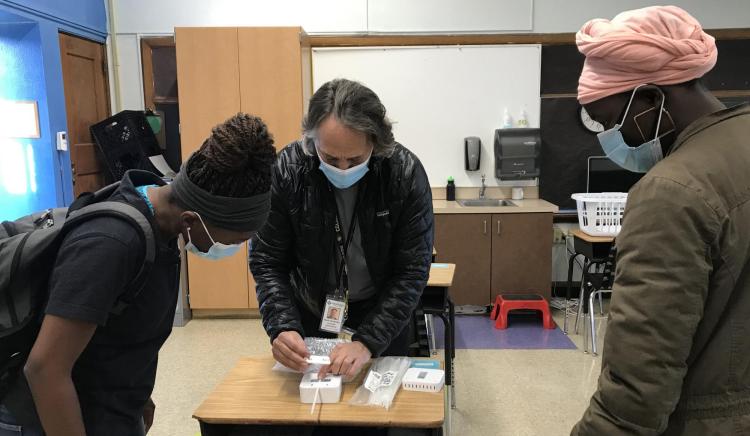

Professor Mark Hernandez demonstrates the installation process for the classroom air quality remote sensors to field technicians Christiane Nitcheu and Sylvia Akol, a CU Boulder environmental engineering student. Photos courtesy Anna Segur.

Results from study on high-efficiency air filters in classrooms look promising

When students in more than 20 Denver Public Schools return to classrooms for the spring semester, they’ll be coming back to cleaner indoor air, thanks in part to work being done by University of Colorado Boulder environmental engineering researchers.

Since the summer, Professor Mark Hernandez and his team have been working in the district’s classrooms to install a new generation of high-efficiency air filters, hundreds of which were provided by Carrier’s Healthy Buildings Program for research.

Hernandez said they’ve been working to quantify how much the high-efficiency filters reduce airborne particle exposure in classrooms, especially when it comes to the COVID-19 virus. The filters use a novel cylindrical design that takes in air from all directions, making them higher flow than their older counterparts for the same footprint.

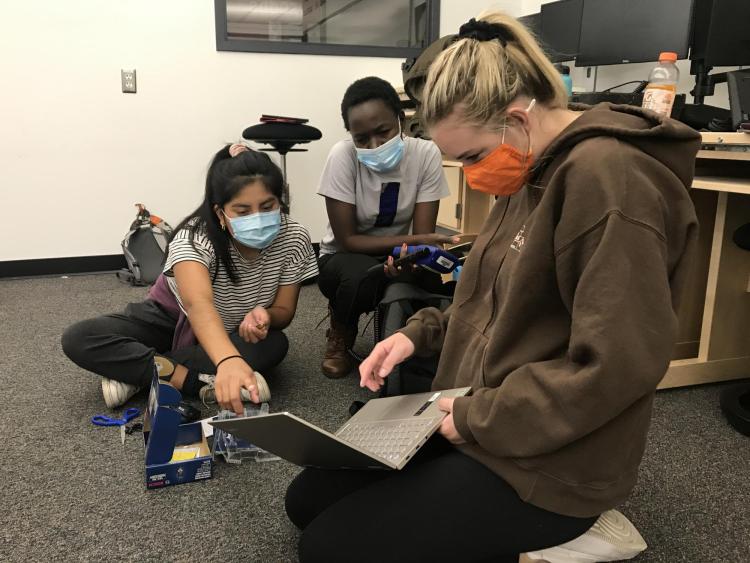

CU Boulder students Halle Sago, Ryan Carroll and Sylvia Akol discuss data input for built environment surveys in Denver high school classrooms.

“There have been a lot of assumptions and modeling efforts out there, which is fine. But the fact of the matter is, in the field with children in the classroom, we have got to verify it,” he said. “The biggest part of this research effort is verifying performance under actual field conditions.”

In addition to Carrier, Intel and Colorado’s Ryan Innovation Group provided philanthropic support for the work.

Hernandez research group has been surveying ventilation rates in schools for many years. He said rates ranged from “terrible” to “as good as a hospital,” which proved to be a valuable starting point.

“We began by focusing on the older infrastructure, as well as those areas with increased asthma occurrence. Now we're trying to bring effective ventilation rates up and get equity across the district’s buildings,” he said. “We're trying to level the playing field with respect to educational environment where the kids spend most of their time. So that's been a really good thing.”

After they measured the ventilation rates, Hernandez’s team took baseline readings of particulate matter – including pollen, mold, bacteria and viruses – suspended in the air of unoccupied classrooms. Then, they used student volunteers and air blowers to simulate the effects occupants have on the shedding and resuspension of airborne particles in classrooms throughout the day.

Once they kicked up the particulate matter, they let the new high-efficiency filters go to work before taking another set of measurements. While Hernandez said they’re still analyzing data, the results so far are promising.

“The preliminary data suggests that filtered indoor air, with regard to re-suspended particle exposures, is commensurate with the outdoors on a good air quality day,” he said, adding that they plan to continue monitoring in partnership with DPS.

This new generation of high-efficiency filters is also remarkably quiet, so as to not interfere with teaching and normal classroom activities, he added. Taken together, that creates an affordable, efficient way for schools to help manage the health of their classroom air, even after COVID-19 is no longer an issue.

“This has important implications for future air quality challenges associated with the intense urbanization of the Denver metro area, as well as increasing wildfire threats,” Hernandez said.

Mike Eaton, the interim deputy chief operating officer for Denver Public Schools, said the project has been extremely helpful in helping the district determine how to allocate funding for additional mitigation.