Forever Buff helped troubleshoot Apollo 11 as the world watched

Stewart Woodward, center, leaning over the LH2 Panel at NASA writing fuel loading times.

It was less than three hours until Apollo 11 was set to leave planet Earth, and Stew Woodward had found a leak in the line supplying liquid hydrogen fuel to the massive Saturn V rocket. The first manned mission to the moon was in jeopardy.

“We knew we couldn't launch unless we could keep topping LH2 into the rocket. In previous test countdowns, even if you thought you could solve your problem, they would say, ‘test scrubbed,’ and hundreds of engineers and techs would pack it in. All because of you. On Apollo 11, with the world watching, the test conductor came back: ‘fix it,’” Woodward said.

John Stewart Woodward, a 1960 graduate of the University of Colorado Boulder with degrees in engineering physics and business, was the lead fuels engineer working at Cape Canaveral for NASA contractor Boeing on July 16, 1969.

His career had already taken him across the country, from Boulder to stops at Atlas intercontinental ballistic missile facilities in Wyoming and Vermont before earning a job at NASA working for General Dynamics on the Atlas Centaur rocket as lead telemetry engineer.

His assignment surrounded the Surveyor program, a series of seven unmanned spacecraft sent to the surface of the moon to determine the feasibility of future manned landings. From there, he was hired by Boeing to work at NASA Launch Complex 39A, which was then under construction and would be the last stop on Earth for Apollo 11 before the moon.

“They started putting up the Vertical Assembly Building and Launch Complex 39A. We were so busy working, we had so much to do, you couldn’t afford to be excited,” said Woodward, now 83 years old. “I got more excited last year during the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 than I did during the actual event.”

On that morning in 1969, there was no room to enjoy the moment. Woodward had a job to do. The leak needed to be solved. They shut down the fueling system, and he dispatched an emergency team to the launch platform. The problem appeared to be on the 200 level of the support tower adjacent to the rocket.

As the team troubleshot the fuel system, the tower elevator whizzed by, carrying Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins to the 320 level, where the trio of astronauts boarded the command module to await launch.

No pressure.

The problem was determined to be a topping valve. It needed to be tightened, but ice had frozen around all of the bolts. Liquid hydrogen is kept at -253 degrees Celsius (-423 degrees Fahrenheit), and the leak had caused condensation to form and freeze into several inches of ice, encasing the valve.

“They were afraid to chip at the ice with hammers. A spark might ignite any residual hydrogen gas in the area. What were we to do?” Woodward said.

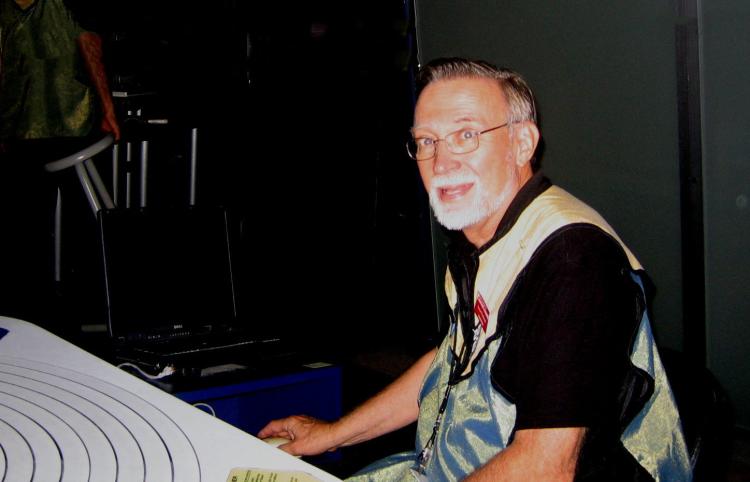

Stewart Woodward volunteering at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science teaching astronomy and aerospace.

The emergency crew fuels engineer had an idea. There was an emergency shower on the 200 level, so the engineers took off their safety helmets and formed a bucket brigade to pour water on the ice and melt it.

“After about 10 minutes, they had melted the ice and used the wrench to tighten the bolts. We opened the main valve, and there was no leak,” Woodward said. “An hour later we launched. Although most of the public thinks it was computers, high technology and well-planned procedures that got mankind to the moon, you have to give a lot of credit to old-fashioned human ingenuity.”

The Apollo 11 launch was but one highlight of Woodward’s professional career, which included later stints in leadership positions at manufacturing and engineering firms in Colorado, before eventually retiring from Martin Marietta as a propulsion engineer. Now 83, he is an avid outdoorsman and is busy in the community.

Woodward spent the past 16 years as a weekly volunteer at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, discussing satellites and manned spaceflight with attendees. He also holds an IKON Ski Season Pass and organizes multiple annual ski and hiking trips for the Flatirons Ski Club. While much of those efforts have been temporarily sidelined by the coronavirus, he is eager to get back outside.

“I’m slowing down as a skier, although I’ve never been fast,” Woodward said. “But I refuse to admit that 83 means elderly.”