"Don't get discouraged" - Jared Leidich - Ep. 9

[soundcloud width="100%" height="166" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" allow="autoplay" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/425780733%3Fsecret_token%3Ds-hkBew&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=true&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true"][/soundcloud]

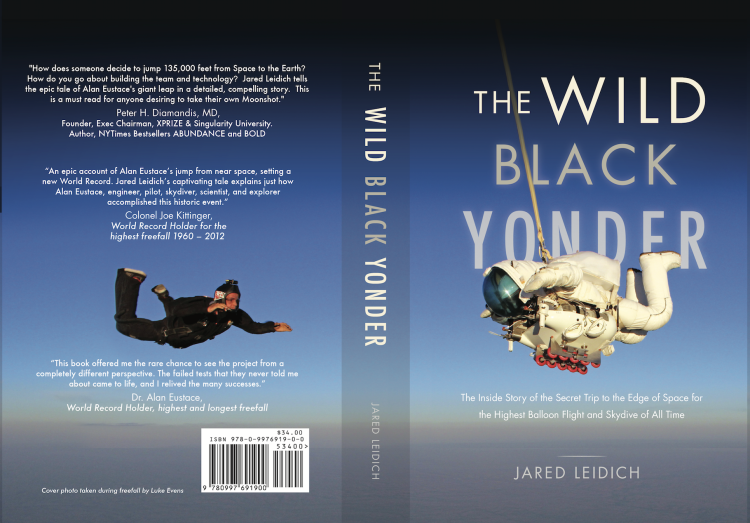

Jared Leidich is a 2009 mechanical engineering graduate from the College of Engineering and Applied Science at CU Boulder. He led the design of the life support pack and parachute system for a spacesuit that carried Google executive Alan Eustace to the stratosphere three times in 2014. He wrote a book about the experience called The Wild Black Yonder, and is now the aerodynamic systems lead at World View Enterprises.

Photos courtesy of Jared Leidich.

TRANSCRIPT

Announcer

And now, from the University of Colorado in Boulder, the College of Engineering and Applied Science presents On CUE. Here's your host, Kellen Short.

Kellen Short

Our guest today is Jared Leidich. Jared’s a 2009 mechanical engineering graduate from CU Boulder. He led the design of the life support pack and parachute system for a spacesuit that carried Google executive Alan Eustace to the stratosphere three times in 2014. The final voyage was the highest balloon flight and skydive of all time. He wrote a book about the experience called The Wild Black Yonder and is now the aerodynamic systems lead at World View Enterprises.

So Jared, welcome back to CU Boulder.

Jared Leidich

Thank you. Great to be here.

Short

I want to start by asking you about that famous stratosphere jump. It was the highest altitude ever reached by a human by balloon. What motivated you to get involved with such an exciting but risky project, especially as a young engineer?

Leidich

Right. So some of my main motivations to get involved with this particular project were one, that it was part of the human spaceflight sphere. I had spent most of my career up to that point working on things that involved humans in space. And the second was Alan Eustace himself, he seemed like a very – uh, that’s the guy who jumped – he was very passionate he was very passionate in the same avenues that I was very passionate in and especially that he wanted to do something to progress science and he wanted that information to be available to the world after it was done. And he wanted to do something in a completely new way, which gave the opportunity for a really exciting experience of inventing something brand new and going through lots of trial and error and lots of sort of invention. And one of the big pieces, I had just come off of a few years of working in a NASA process environment. And I did work on a few projects that, really characteristically of modern NASA projects, didn't ever fly or get finished, and doing something for an individual that had a lot of drive and the funding to do this made me think that it was -- actually had a good chance of actually going to the sky.

Photos courtesy of Jared Leidich.

Short

That’s fantastic. And in the book you describe a lot of the technical questions that you have to answer, creating this spacesuit and making sure that it could sustain life. It was the heating system and it was the extreme cold, the proper oxygen system, the parachute system. Is there any one thing that you can pinpoint as the biggest challenge of this project?

Leidich

So, I think when looking at what the biggest challenges of a project like this are… there are really two fundamental problems that we entered the project without knowing a real solution to: one was how you contain all of this heavy, voluminous life support equipment in one suit and the suit was unique in that it was suspended underneath a balloon with no other support equipment. So all of his life support was attached to him, so that was almost a packaging problem. Every time anything like this had been attempted in the past there was this gondola or capsule that held hundreds and in most cases thousands of pounds of equipment, and we had to shove that all into one spacesuit.

The other was the descent system, the descent portion of this. At the time we started, the project came with some pretty terrifying odds that of the four people who had attempted stratospheric skydives in the past, two of them died during their jumps, and a lot of the problems that led to those situations hadn't really fully been solved, so that the parachute system and particularly how you stabilize a person so that they won't spin and can get a stabilized parachute above them before they start to fall were, those are two of the big problems that stand out and occupied a lot of our time through the whole project.

Short

How long did you spend on the project?

Leidich

It was about three years of me working on it. Alan started thinking about the project about a year before he came and talked to Paragon and that was the point when I really got involved. I think that it was early 2010 that Alan really started thinking about this problem, early 2011 is when he talked to Taber MacCallum at Paragon and Paragon kind of got involved. In February-March 2011 is when I got involved, and the jump was October of 2014.

Short

That’s incredible. And I know that you talked about the terrifying odds of a project like this and I know that you served even as a test subject kind of for the suit in some early trials. Anything go wrong there?

Leidich

Yes. So I was, just by coincidence, was roughly the same physical size and shape as Alan. You go through a space suit measuring process of 54 measurements, and all of my measurements, they measured several people and all my measurements happened to be within the allowable band so that I could use the suit. Early in the project the first time we ever pressurized that exact suit, so essentially a procedural failure where a valve got turned off while I was in the suit and none of us, including me, really understood the direct ramifications of turning off the particular valve that was turned off, and the head of the suit was quickly evacuated and I was left suffocating inside the suit. A second outcome of that was that the mechanism that holds the helmet down was now in a vacuum and the helmet was kind of stuck down, so I don't remember a lot of the last pieces of it but there was a struggle of about four people to get the helmet off the suit -- again, nobody really knew what was going on at the time it was happening -- but the helmet was suctioned onto the suit because of that evacuated head region. So that was a scary event from early in the project and through that and lots of drop testing and skydiving, yeah, we did that. All of the major players in that program took a lot of personal risk and, yeah, something that comes with a program like that, something we were constantly in struggle with was risk to Allen and risk to ourselves. We had conversations, you know, mostly almost daily about whether the risks we were taking were acceptable and when to back off and take longer and to push harder.

Short

That’s terrifying. Did anything surprise you though through the process? I mean, was there anything that was easier than you expected?

Leidich

I don't think anything was easier we expected. The original proposal was supposed to take 10 months, and we ended up taking about three years. Just about everything, if not everything, was harder and took longer than we thought it was going to. And I found this to be a theme with projects that are on the cutting edge, that nobody would start them if they had any idea how hard they actually were going to be. And so everybody kind of tells themselves this nice story about how it's going to be quick and easy and then it's going to be glorious. And then when it doesn't happen that way, you're already so deep and so invested that you keep going even though you probably wouldn't have started it if you could go back in time.

Short

That makes sense. I think the one thing that would drive me if I were working on a project like this is that it has that definite 'cool factor.' But talk to me a little bit: what's the scientific value of a jump like this?

Leidich

Yeah, so, the stratosphere in general is a relatively unexplored space. So spacecrafts go through the stratosphere but they're in it for a very short amount of time when they're transiting to low earth orbit or wherever they're going. Re-entering vehicles come back through the stratosphere. Aside from that, there's very little in the stratosphere, and that gives it some serious potential as a place to do a lot of things, and some of the big ones are: understanding its properties for things like weather and how that part of the atmosphere is filtering things and affecting things below it. And majorly as is a space that has room to expand so is the troposphere at the lower altitudes are getting filled with airplanes and drones and whatever else are getting filled with, orbit is getting full, there's this kind of an empty band that is for, to some degree, just an open space that's not full yet. So we can do things like communicating and Earth observation and all the stuff that you do from satellites and bringing people there and using people to explore how the human body interacts with this space. And you can do it without a whole lot of competing for space and regulation because right now it truly is mostly empty aside from a few weather balloons that go through it. And companies like the company I currently work for and a couple others putting stratospheric balloons up there. There's not a lot going on. There's only, you know, less than a handful of people that have ever spent more than a couple seconds there.

Short

And you wrote your book sort of in secret based on the notes that you were keeping through this process. How was it received by other members of the team?

Leidich

Yeah, it was pretty -- it was pretty scary to show people that this existed. And I had no idea how that was going to go. Through this process, me and this group of people, we lived together in hotels and weird desert towns for, you know, huge amounts of time. We had gotten extremely close, and then I'm going to drop this bomb on them of like, hey, I've been watching you and writing down what I see for the last little while and now I'm going to publish a book about it. So it was scary. But when it happened, it was incredibly well-received and everybody was nothing but excited that their project was getting documented. I think there was a -- I had a fear and I think a lot of people had this fear that it was, that it was going to get lost. And it was cool and has this cool factor, but it was kind of a blip in the media world and may have. You know I think all of us were worried it was going, it would fall into oblivion with a bunch of other things that were kind of, you know, one-shot wonders and we, I, really wanted to make sure that when people wanted to do things like this in the future and if people wanted to learn the same lessons that we were, that we learned, they had a way to do that. I think a lot of our team felt the same way.

Short

You said it's gotten confused sometimes with the Red Bull stratosphere jump that happened within a few years.

Leidich

Right. So we were kind of going on in parallel to Red Bull Stratos, and Red Bull Stratos had started when we started but they had not done any jumps when we started and it wasn't crystal clear they were going to do any jumps. There were several teams trying things like this and several projects that had kind of come up and died out, so Alan didn't really let it deter him that Stratos was going on, and he viewed his jump as fundamentally different. His real innovation was getting rid of the capsule and getting rid of the gondola and really focusing on the suit. He likes to make an analogy to scuba diving and the innovations of Jacques Cousteau saying this, you know, like, screw this submarine, I'm just going to go down there with an oxygen tank, and how much that freed explorers to see that space. He wasn't deterred by the fact that Red Bull Stratos existed, about two years into the project, a year before we did our final jump, Red Bull Stratos did their jump and it was this huge media event. And so now there's this unfortunate, the names are really similar. And that was this really big media event. Our project was secret and we didn't tell anybody about it until the day that Alan jumped and those, the mixture of those things made it such that it's really easy to confuse the two. For the most part I think if I say I was part of StratX, the world’s highest skydive, they’re like 'Oh, the Red Bull thing, that was really cool I watched that on YouTube.'

Short

Well, all the more reason to write this book, then, to really tell the untold story.

Leidich

Certainly.

Short

So I want to go back a little bit to your CU Boulder days and ask you first how you decided to get into engineering, and how did you pick CU?

Leidich

Yeah, so, I have been kind of obsessed with space since I was very young. I, toward the end of high school, interned at Lockheed Martin on the Orbital Space Plane Project, and that just got me more into space. I have three older sisters, two of which were CU engineers. My family has lots of engineers, so we’re a very engineering-focused family. I did tons of tinkering when I was a kid. I had three older sisters, and my dad got really excited about tearing cars apart and whatever else with me. So I was pretty set on engineering and my sisters loved it here. It's close. It worked. So, yeah, it was kind of a no-brainer.

Short

That's great. You describe yourself as 'not academically exceptional' yet you worked some incredible projects at CU. I know you had installed cookstoves in Rwanda with Engineers Without Borders. You flew twice on NASA's microgravity planes. Your senior project was the judges' pick at the design expo. What was the most meaningful thing you accomplished as a student?

Leidich

Yeah, so, I do tend to think that I'm not academically exceptional. I struggled really hard to make it through my classes and get good grades. I was not a perfect student. And I think I did really excel in the project world, and that's -- that was my conduit to the job I got. And that's where I made my closest contacts through my life now. And those projects are really what kept me going and kind of picked me back up when I would have a hard time with my classes and I, to this day, I love a good engineering project, and that's what I spent a lot of my time doing. Yeah, so, I was part of Engineers Without Borders from early in college. That connection with Engineers Without Borders led me to Dr. Evan Thomas, who was my advisor, who I worked on these NASA projects under, and then he’s really the contact that got me that job at Paragon. And then alongside that, I worked on the DANDE project and was really into like, freshman projects and senior projects and spent way too much time doing that. Not enough time doing my schoolwork, so yeah.

Short

It's turned out OK.

Leidich

Yeah, it all worked out.

Short

I'm curious if you have any advice for current students or any young people thinking about becoming engineers.

Leidich

Yeah, so I think if I look back at my college days, the things that I think worked really well for me was getting involved in that project world, and be part of as much of this cool stuff as you can. I think it's easy to miss how much opportunity there is around you every day here until you leave and you realize that you've really got to work to make an opportunity become available once you're out of school and, you know, while you're in a place like CU, there's going to be up opportunities abounding all around you and to embrace them and get involved with them. And I guess for me personally: don't get discouraged. I can't say I never failed a class, but I did take it again and I passed it and everything worked good. So I think especially those early years in engineering school can be really brutal, and stick with it.

Short

Good advice. I'm not sure how you could go back to work after completing a project of this magnitude. So what was it like after you finished and what have you been doing since?

Leidich

So, we kind of got slingshotted out of that project. I was really planning on taking a couple months off and getting my head back on my shoulders, but that didn't quite work out. Two of the founders of Paragon, the parent company that was the prime contractor for that StratX project, founded a new company called World View, and that company does a lot of similar things to what StratX did in that they’re -- it's stratospheric, balloon-based research. So they're taking the stratosphere platforms up to anywhere between like 60- and 120- or 130,000 feet and doing all sorts of research from those platforms and at the beginning, we are, our biggest project was building a manned capsule to take six to eight people to the stratosphere at a time. That capsule was called Voyager, and that started up pretty much immediately, and that original team was given this, you know, really we want you to come join us but you've got to come now. So yeah I started right into that, and that's what I've been doing since. The company has grown a huge amount. We went from 11 people in a rented room to now we’re an 85-person company. It relocated to the brand new Spaceport Tucson, so that's what I've been doing since. It's been -- continued to be -- extremely exciting.

Short

That's great. Not sure anything could top that. So glad to hear you're still involved and excited about the work. And you were also involved with the documentary 14 Minutes from Earth. What was your role in that, and how did you get involved?

Leidich

So, Alan, at the beginning of the project, he knew that it was going to be secret or that we weren't going to do a lot of external publicity for the project. And I don't know all of the details about why that was, but we knew from the beginning that this was not something that was going to be publicized. I think probably for that reason he wanted to have this video record of what was going on.

So there is this video documentary created, kind of following us along through this long project. And I got along well with the video guys, and I just ended up being a major role in the video partially because of my role in the project and, yeah, got turned into a documentary.

Short

Is it weird to watch yourself onscreen?

Leidich

Yes, it's very weird especially throughout the life of the project. You can, you can look back in time and watch yourself being extremely naive at the beginning, you know, 'We’re going to be done in a month, and it’s going to be great.'

Short

That's brilliant. Probably a few more gray hairs formed throughout that film.

Leidich

Yeah.

Short

Thank you so much for being here. This is a pleasure to talk to you and best wishes for the future.

Leidich

Yeah, thank you, it was great to be here. That was fun.

Announcer

This has been On CUE. For more information, visit colorado.edu/engineering.