5 burning questions about ChatGPT, answered by humans

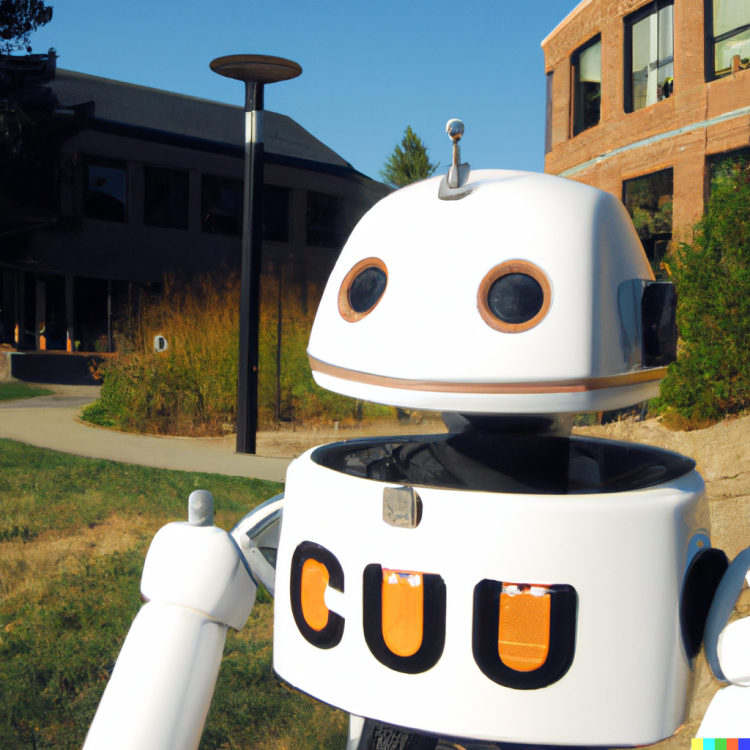

This robotic buffalo statue on the CU Boulder campus doesn't exist. The image was generated using DALL-E 2, an artificial intelligence platform launched by OpenAI in 2022.

This sentence was not written by ChatGPT. Later on in this story, you’ll find a paragraph drafted by the popular artificial intelligence platform (it’s up to you to decide which paragraph). But, for now, what you read is all human.

OpenAI, a San Francisco-based laboratory, released ChatGPT in November 2022. Fleshy humans took note: The advanced chat bot could seemingly do it all—with a simple prompt via text, it could generate unique tweets, poetry, term papers on Freudian psychology and even, as one CU Boulder professor discovered, a children’s books about an unhappy cockatoo.

Some critics have raised the alarm that students could use ChatGPT to crib entire essays or college applications. Others worry such AI platforms might put certain professionals, such as K-12 teachers or university science writers, out of work.

Concerns or no, ChatGPT seemed to carry a message: The age of artificial intelligence is here.

“We are at an inflection point for this kind of AI,” said Casey Fiesler, associate professor in the Department of Information Science at CU Boulder. “It feels to me like the very early days of widespread adoption of the internet in terms of how impactful this could, eventually, be for everyday life.”

CU Boulder Today spoke with Fiesler and three more technology experts on campus: Daniel Acuña, associate professor in the Department of Computer Science; Peter Foltz, research professor in the Institute of Cognitive Science; and Kai Larsen, associate professor in the Leeds School of Business. They touched on what the future holds for ChatGPT and what it might mean for people.

From left to right: Daniel Acuña, Casey Fiesler, Peter Foltz and Kai Larsen

Wait. Sorry. What is ChatGPT?

ChatGPT is based on OpenAI’s Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3). It belongs to a class of tools called large language models, which human programmers train using huge amounts of text. Put simply, ChatGPT is really, really well read, said Larsen, who’s written a book about AI in business.

“Let’s say you take a human being from around 700 B.C., roughly around when Homer was alive,” Larsen said. “You have him read books and scrolls 24/7 for 2,700 years. That’s about how much information was put into this thing.”

When prompted, ChatGPT will draw on that learning, plus extensive training sessions with real humans, to draft its responses. You can ask it: “Should I apply to the Leeds School of Business?” or, “Tell me a limerick about Ralphie the buffalo,” and it will reply with surprisingly cogent answers—all in a matter of seconds.

ChatGPT has some competition, too: Google announced earlier this month that it would soon release its own, similar tool, which the company has dubbed “Bard.”

None of these models are especially new, Foltz noted. In the 1990s, for example, he and his colleagues developed a tool called the Intelligent Essay Assessor that could read and grade student essays—with about the same skill as a college professor. He and his colleagues sold the software to the educational publishing company Pearson in 2004.

“ChatGPT is one of the first cases where such a tool has been released in a way that people everywhere can see it and play with it,” Foltz said.

Q&A with ChatGPT

To learn more about ChatGPT, CU Boulder Today went right to the source: ChatGPT. We asked the platform about the future of AI in education, reproducing its responses verbatim. All questions were prefaced with a request to “please keep your response to a few sentences.”

CUBT: Some people are concerned that ChatGPT will put certain professionals, such as teachers or journalists, out of work. What do you think?

ChatGPT: Artificial intelligence and machine learning have the potential to automate certain tasks, potentially leading to job displacement. However, these technologies can also create new job opportunities, increase productivity, and provide support to professionals in their work. It is important for society to approach the integration of these technologies thoughtfully, balancing the potential benefits with the need to ensure that the transition is smooth for affected workers.

CUBT: Please answer the same question, but like a super sarcastic teenager.

ChatGPT: Oh sure, because a machine that can only provide limited and pre-written responses is totally going to replace human professionals who have years of education and experience. I mean, who needs critical thinking and emotional intelligence when you’ve got ChatGPT, amiright? eye roll

CUBT: Can you describe the future of AI in education in the style of a romance novel?

ChatGPT: Oh, the future of AI in education is a love story for the ages. With every step forward in technology, the passion between man and machine grows stronger. AI will sweep education off its feet, caressing it with the gentle touch of data-driven insights and empowering it with the gift of personalized learning experiences. The two will become intertwined, hearts beating as one, working together to create a brighter, more efficient future. And who knows, perhaps one day they will even conceive the next generation of education together.

CUBT: How can teachers prevent students from committing plagiarism using AI tools? Pretend you are a pirate.

ChatGPT: Arrr matey! To keep students from swiping content and presenting it as their own booty, teachers can use AI tools to check for any signs of plundering. By running the student’s work through these scallywag-sniffing machines, educators can catch any instances of copied loot and make sure the students are writing their own pieces, fair and square. So hoist the Jolly Roger, it’s time to set sail on a voyage to clean up the seas of academic dishonesty!

CUBT: Those are all my questions. Sko Buffs!

ChatGPT: Go Buffs!

CUBT: Partial credit.

I don’t care for limericks. What else can ChatGPT do?

Loads. ChatGPT is adept at writing and editing basic computer code in different programming languages. Fiesler, who studies technology and ethics and has posted several videos about ChatGPT on her popular TikTok channel, tried something else: She asked the platform to write her a statement of purpose for applying to CU Boulder’s doctoral program in information science.

“I said, as part of this statement, include how your research relates to Dr. Casey Fiesler’s,” she said. “The answer was really good.”

Larsen, meanwhile, leaned into the whimsical. He used ChatGPT and DALL-E 2, a similar program for generating images, to create a children’s book about his beloved pet called Dewey the Unhappy Cockatoo.

ChatGPT is still available for free. But OpenAI and its competitors will inevitably find a way to monetize every interaction with its models, Larsen said. He thinks large language models will excel at some of the most boring tasks of all: writing routine office emails.

“At its core, it's a communications model,” Larsen said. “Anytime human beings are communicating with each other, we're going to see opportunities for using artificial intelligence tools to help them communicate faster.”

Why are people freaking out?

Because that’s what humans do. Admittedly, experts have raised a number of concerns about ChatGPT and its implications for the economy, schools and more.

The AI platform, for example, is a gifted liar. Acuña explained, in its guts, ChatGPT works like the autofill feature in Google search. If you give it a few words, it will come up with possibilities for the words most likely to come next, then generate text based on those predictions.

“ChatGPT predicts the next word with some randomness factored in,” Acuña said. “It does it very, very well.”

That means, however, large language models will sometimes generate text or computer code that looks correct on the surface but is actually completely wrong—in some cases, inventing facts out of thin air, what AI researchers call “hallucinations.”

Google’s Bard did just that during a public, and potentially costly, demo Feb. 6: The platform claimed that NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope had taken the first-ever images of a planet outside Earth’s solar system. (The honor actually belongs to the Very Large Telescope in Chile, which snapped an image of an exoplanet in 2004, nearly two decades before James Webb launched.)

What keeps Larsen up, however, aren’t those sorts of computerized lies, but something, perhaps, much more relatable.

“It will make it easier to communicate fast, which kind of scares me,” Larsen said. “Communication should be insightful and valuable or make us feel better. But it should not be more frequent. I don't know about you, but I get enough emails.”

Will my children be taught by robots?

Fiesler has spent a lot of time thinking about what ChatGPT might mean for her own college classes. She acknowledged that students could, potentially, use it to cheat—writing term papers in less than a minute.

But she believes that plagiarism is the wrong thing to focus on.

“I am more concerned about making sure the students who deserve an A get an A than making sure the students who don't deserve an A don't get an A,” Fiesler said.

Instead, she wants to know how ChatGPT can help her students learn. For an assignment, undergrads might, for instance, be asked to use AI to generate the first draft of an essay, then critique it: What did ChatGPT get right? What did it get wrong? Where did its arguments fall short?

Foltz added that, one day, AI tools might serve as 24/7 tutors for students of all ages. A platform like ChatGPT could give high school students instant feedback on their five-paragraph essays or help middle schoolers with their algebra homework.

These AI partners might not be as skilled as flesh-and-blood people, but they could help fill a gap for the many who can’t afford human tutors, Foltz said. He is executive director of a $20-million National Science Foundation institute, which explores how AI can transform classrooms—and in ways that seek to reduce the inequalities in education, not make them worse.

DALL-E 2 generated this image from the prompt "photo of a friendly robot with 'CU' on its chest visiting the University of Colorado Boulder campus."

Is this the beginning of the machine revolution?

“My view is that this is a ‘don’t panic’ moment,” Foltz said.

ChatGPT will almost certainly lead to job losses in some professions, Larsen added. The Associated Press, for example, has used AI software to write stories about minor league baseball games since 2016.

“The question we have to figure out is how many more new jobs is it going to lead to,” Larsen said.

All four experts agreed that in the ensuing decades, it will become more important than ever for people to learn about what AI can do—and what it can’t.

Despite the potential benefits, some people may have concerns about ChatGPT due to a natural distrust of AI. This distrust stems from the fear of machines becoming too powerful and surpassing human abilities, leading to job loss and other negative consequences. For example, the public was initially frightened by IBM's Deep Blue, a computer designed to beat the best human chess players. However, as Acuña pointed out, just because a computer excels at one task, such as chess, it doesn't mean it can perform other tasks just as well.

“People extrapolated the success of Deep Blue to other human activities. But Deep Blue was better than humans at playing chess,” Acuña said. “At that time, that didn’t mean that a computer could also play poker as well as the best players in the world.”

Found it yet?

As for the paragraph written by ChatGPT: It’s the one above about humanity’s natural distrust of AI beginning with, “Despite the potential benefits …”

Who did it better, the machine or organic organism, is up for debate. Reached for comment, ChatGPT itself responded:

“The future is likely to be a collaboration between humans and AI, rather than one overtaking the other.”

CU Boulder Today regularly publishes Q&As with our faculty members weighing in on news topics through the lens of their scholarly expertise and research/creative work. The responses here reflect the knowledge and interpretations of the expert and should not be considered the university position on the issue. All publication content is subject to edits for clarity, brevity and university style guidelines.