AR Drum Circle research envisions enjoyable remote jamming experiences despite latency

Long before the pandemic sent people scrambling into isolation, musicians have longed to jam virtually with others across the globe. Now researchers from CU Boulder’s ATLAS Institute’sACME Lab and Ericsson Research are developing ways for musicians to play together remotely through the AR Drum Circle project.

The difficulty with online jamming has always been latency, the tiny delay that occurs when data is transmitted from one point to the next, says Torin Hopkins, an ATLAS PhD student who leads the ATLAS team. Video conferencing participants don’t detect the delay because they generally take turns when speaking, but any lag greater than 20 milliseconds makes synchronous singing or performing unworkable, he says.

“There’s no room for delay in musical collaborations,” says Hopkins, adding that the virtual choir videos popular during the pandemic were mixed in post production. “Yet real-time music-making with zero lag and a consistent video stream currently doesn’t exist.”

In the AR Drum Circle project, ATLAS researchers and Ericsson project collaborators are exploring ways in which remote drumming experiences can be made more enjoyable despite the latency, says Colin Soguero, the project’s app developer and an undergraduate student studying Creative Technology & Design.

“Latency is one of the biggest issues with remote collaboration, and it can be very frustrating for musicians who rely so heavily on precise coordination,” he says.

Jamming with Avatars

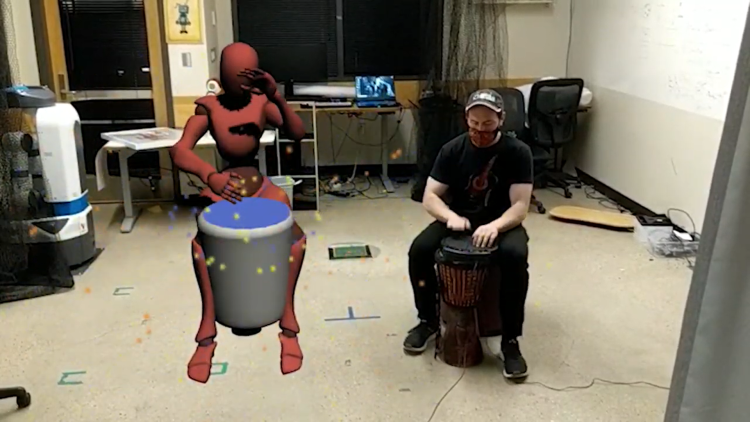

Some of AR Drum Circle’s research focuses on avatars, computer-generated figures that in this case replicate the actions of real drummers participating remotely in drum circles. The avatars appear in another musician’s surroundings using augmented reality (AR), a technology that superimposes a computer-generated image on a user's view of the real world.

Using the AR Drum Circle application, Musician A prints a QR code and places it to position Musician B’s avatar in the augmented reality view. Musician A’s Android cell phone runs the application, and displays B’s avatar where the coded picture was placed. Musician B does the same. When either musician strikes a drum pad connected to their computers, the computers send that information through the internet, the corresponding avatar drummer then strikes its drum, and a drum beat is heard in both locations. The technology employs a Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) controller, which, when one drummer strikes their drum pad, sends information to their computer, which then sends the data over the internet to the other drummers’ locations.

While live video of the drumming partners might be best, using avatars mediates the perception of the latency and—potentially—provides visual and audio information for a more satisfying musical exchange, Hopkins says. It takes just small bits of data to trigger an avatar's hand to move, whereas rendering videos requires large amounts of data to transmit every pixel of the moving images.

Adding to this, the core idea of this project is not merely collaboration, but how to minimize or leverage the effects of the inevitable latency and jitter (the deviation from true periodicity of a presumably periodic signal) in order to make collaborations that are highly sensitive to timing more successful or fun, says Mark Gross, professor of computer science, ATLAS director and a member of the project’s advisory team.

“Latency cannot be avoided, but its effects can be mitigated by being clever in portraying avatars and by anticipating future actions,” Gross says.

Sending the drum pad information over the internet to a receiving computer is “incredibly complex,” Hopkins adds. The data travels a long journey and encounters many checkpoints along the way, and small packets of information travel much faster across the network than video with sound. Because the avatar's motion needs to be realistic, complex information is kept on the receiving device and only “start animation” messages are sent over the internet.

Enjoying the experience

Just watching and hearing an avatar strike a drum doesn’t provide adequate information for remote drummers to synchronize, says Ellen Do, professor of computer science with ATLAS, who also participates in several drum circles. Drummers often use gestures, such as head motions and eye contact, to indicate part changes, turn taking and solos, she says. They also use striking force to control volume and hand position to control the timbre; they need to recognize the patterns of the rhythms (e.g., focusing on the down beats, space in-between the beats, the speed, embellishments, harmony, etc.) to play with others, she says.

A large part of the team’s research focuses on determining which of those gestures and expressive features might help remote drummers feel immersed in the collaborative musical experience and experience the enjoyment of feeling connected with each other, she says.

Hopkins, who plays guitar, piano, ukulele, bass, and drums, as well as sings, has missed jamming with other musicians during the pandemic.

“Meeting new people, sharing new ideas and the audiences– those are the things that I really, really miss,” Hopkins says. “Part of the project is figuring out how to incorporate that. Every time I hit the drum, is that enough to make you feel like I’m listening to you? That you feel connected, and that we feel in-sync with each other?”

Connecting in an isolated world

Over time the researchers plan to expand the study to include different types of musical jams, such as including more drummers, musicians playing different instruments, and even dancers that would interact with drummers, as might happen in a physically co-located drum circle, says Do.

Soguero adds that the researchers are also exploring looping, which allows a player to record a drum beat and play it back later, as well as pseudo-haptics, visual effects created in a virtual environment that trick the brain to believe that it’s receiving information about touch and feel.

Regardless of the pandemic, connecting with people who are geographically distant allows for rich, connected, experiences with others who have a variety of talents, come from different cultures and have different perspectives, Hopkins says.

Lessons learned from the AR Drum Circle study about human-human communication, or human-agent communication (with an avatar, agent or robot) could also possibly inform other computer-supported collaborative work scenarios, such as remotely collaborating in medical procedures or auto-repairs, Do says.

“Our research raises the question, ‘Why collaborative musical experiences?’ ” says Hopkins. “Are we doing it to enjoy the company of others or because we enjoy music? How much can you strip away from either experience before you realize they are so intimately connected that designing for collaboration or musical expression alone feels disingenuous?

“Therefore, when designing the AR Drum Circle application, we focus on player-centered design strategies. Maximizing play, given the constraints of the mediating technology (augmented reality) and activity (drum circles), enables the players to feel a sense of contribution in a musical collective, giving us a much needed sense of connection in an isolated world.”

AR Drum Circle's ATLAS Team: Torin Hopkins, ATLAS PhD student, is the project manager; Darren Sholes, ATLAS PhD student, is the technical lead/network engineer; Peter Gyory, ATLAS PhD student, was the former technical lead; Hooman Hedayati, PhD student in computer science, is the project's network engineer and advisor for human-robot (avatar) interaction; and Colin Soguero, an undergraduate student studying Creative Technology & Design, is the app developer. The advisory team consists of Mark D. Gross, ATLAS director and professor of computer science; Ellen Do, ATLAS and computer science professor; Amy Banic, associate professor of computer science at the University of Wyoming and visiting ATLAS professor; and Dan Szafir, ATLAS and computer science assistant professor.

Ericsson Research Project Collaborators: Amir Gomroki, head for 5G, North America; Héctor Caltenco, senior researcher; Per-Erik Brodin, research engineer; Ali El Essaili, senior research engineer; Chris Phillips, master researcher; Alvin Jude Hari Haran, senior researcher; Per Karlsson, director, media technology research at Ericsson and head of Ericsson Research in Silicon Valley; Gunilla Berndtsson, senior researcher at Ericsson Research, Media Technologies.

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7PhJRmLt1w&feature=youtu.be]