Kate Goldfarb's Collaborative Marshall Fire Narratives Featured in CU Magazine

In the article, Professor Kate Goldfarb discusses the collaboration between CU Boulder and the Louisville Historical Museum and their efforts to preserve narratives from the devastating Marshall Fire.

Around 11 a.m. on Dec. 30, 2021, a wildfire ignited in dry grass near Marshall Road and Colo. 93 in Boulder County—and several months later, inspired a novel collaboration between the University of Colorado Boulder and a local history museum.

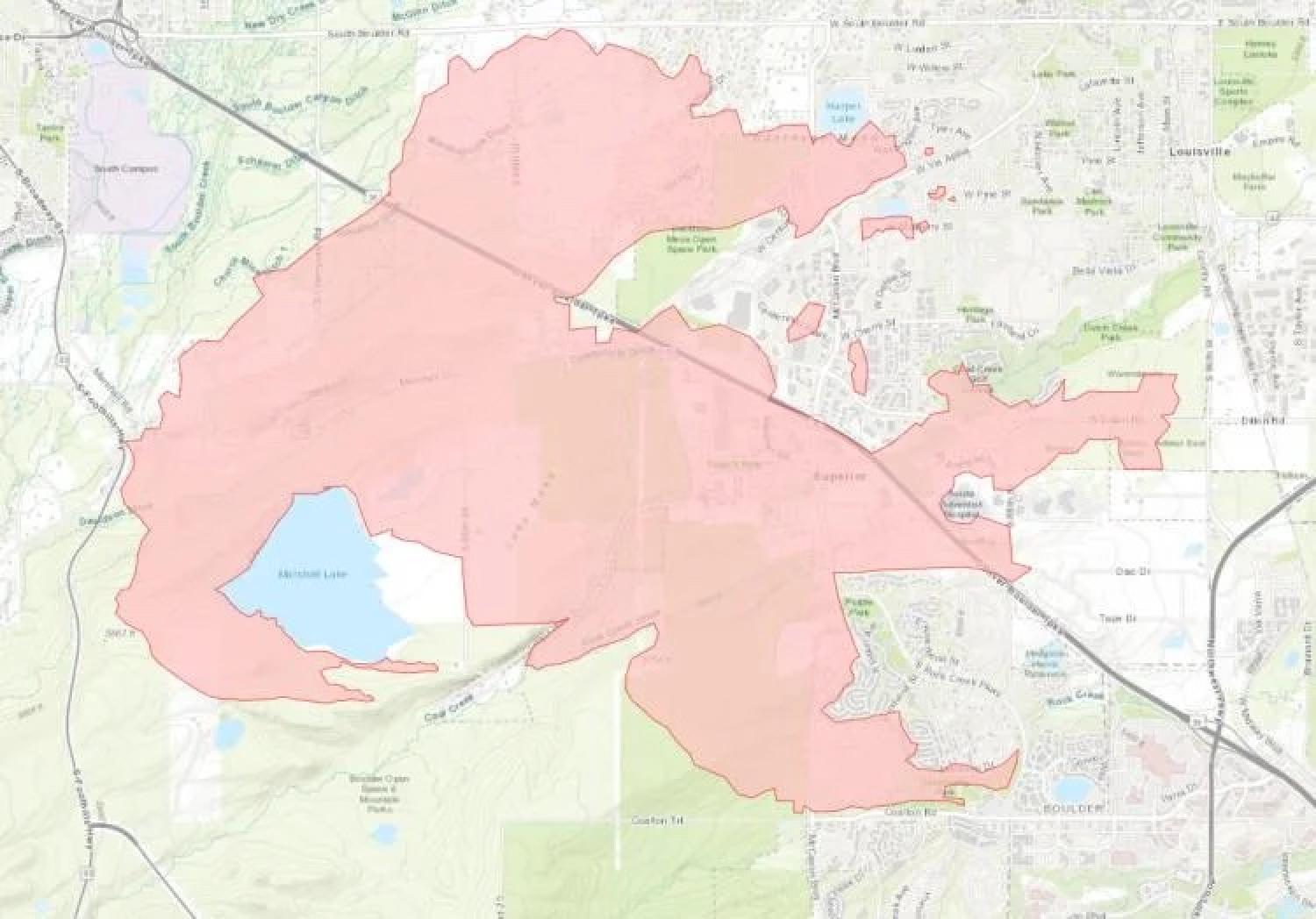

Driven by winds gusting up to 115 mph—more than 150% faster than “hurricane force” winds, according to the National Weather Service—the fire blew up almost immediately, sending choking clouds of smoke in a vast, eastward plume.

Forty minutes after firefighters first arrived, thousands of residents in Superior, Louisville, Broomfield and nearby areas were ordered to evacuate. By the time a snowstorm had doused the blaze some 36 hours later, it had roared through more than 6,000 acres, destroyed more than 1,000 structures, mostly homes, killed two and cost more than a half a billion dollars to fight, making it the most destructive fire in Colorado history.

In the wake of the disaster, devastated staff at the Louisville Historical Museum, some of whom had been forced to evacuate, wondered how they might help a shocked and reeling community understand and recover from the trauma.

“We are museum people, we have an oral-history program, and the answer was, one way we can help the community is with stories,” says Jason Hogstad, volunteer services museum associate.

Honoring the museum’s mission to share and preserve the stories and lives that “make up the heart and character of Louisville,” the staff created the Marshall Fire Story Project to facilitate ways for people affected by the fire in any way to share their experiences for the historical record. In February, the museum held the first on-site workshop and launched an online platform to gather residents’ stories.

Not long after, something unexpected happened: students at the University of Colorado Boulder stumbled upon the Marshall Fire project while seeking information about air quality in the wake of the fire for Assistant Professor Kate Goldfarb’s advanced practicing anthropology course.

“I’m developing a research project about community experiences of air quality, ‘Knowing Air,’” says Goldfarb, a Boulder native who returned to her hometown to teach at CU Boulder in 2015. “With the Marshall Fire, air quality and potential health impacts of dust and burned materials were an immediate concern.”

The students contacted Hogstad and the museum and asked if they could collaborate in some way. The museum shared some data, but the students were eager for a more hands-on experience, particularly speaking with those affected by the fire, which also impacted the CU Boulder community, with one former regent losing their home of four decades.

“It was the students who really piloted this effort,” Goldfarb says. “I trusted them and was impressed by their high regard for Jason and the Story Project.”

Goldfarb contacted Hogstad (whom she’d never met) to ask if he’d be interested in putting together a proposal for a $5,000 CU Boulder Community Outreach and Engagement Grant to support the project with student help.

Even though the request for proposals had an eight-day turn-around, the museum enthusiastically jumped in. The grant was awarded in June. One of Goldfarb’s practicing anthropology students, anthropology and linguistics major Emily Reynolds, will continue work on the project, along with incoming anthropology master’s student Lucas Rozell. The students will assist in “whatever needs to be done, transcription, video processing, mobile story-collecting” or anything else, Goldfarb says.

“The project’s purpose is threefold,” according to the grant application: “To create a community archive useable by community and academic researchers, provide a space for affected individuals to share their story (a critical part of processing trauma), and offer the entire community a place to have their voice heard and added to the historical record. By the end of the project, we hope to have all audio and video stories processed and ready for use by researchers.

The project will also capture hundreds of GoFundMe campaigns created in response to the fire.

Read the entire article here: CU Magazine