CUriosity: A 50-year-old Soviet spacecraft will soon crash to Earth. Why, and where will it land?

In CUriosity, experts across the CU Boulder campus answer pressing questions about humans, our planet and the universe beyond.

This week, space weather experts Charles Constant, Marcin Pilinski and Shaylah Mutschler answer: “A 50-year-old Soviet spacecraft will soon crash to Earth. Why, and where will it land?”

An aurora seen from the International Space Station reveals the influence of the sun on Earth's atmosphere. (Credit: NASA/JSC/ESRS)

Later this week, a piece of Cold War space history is expected to return to Earth—although where it will land remains unclear.

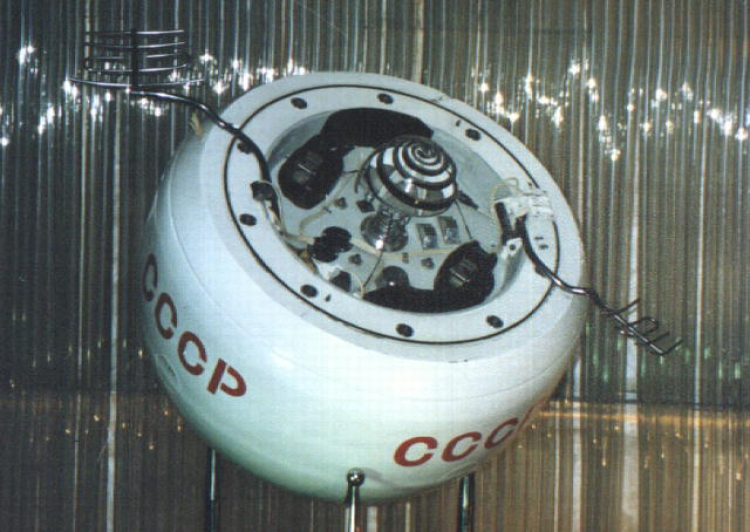

Scientists estimate that Kosmos 482, a Soviet spacecraft that launched from Earth in 1972 with plans to land on Venus, will reenter Earth’s atmosphere sometime this weekend. The spacecraft, which was fortified to withstand the extreme conditions at the surface of Venus, will likely reach Earth’s surface intact.

Don’t panic: The odds that this relic will land in a populated area are very low, said Marcin Pilinski, a research scientist at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The Kosmos 482 Venus lander. (Credit: NASA)

“It’s an infinitesimally small number,” Pilinski said. “It will very likely land in the ocean.”

He’s keeping a close eye. Pilinski is part of a team of scientists that has tracked Kosmos 482 as it orbited Earth. They include Shaylah Mutschler, director of the space weather division for the company Space Environment Technologies, and Charles Constant, a doctoral student at University College London.

The researchers say that the case of Kosmos 482 shows why it’s so important for scientists to get a handle on the space environment around Earth—understanding how spacecraft orbit the planet, interact with its wispy upper atmosphere and, in some cases, fall back down.

It’s a story five decades in the making: Kosmos 482 set out for Venus in March 1972, but, due to an unknown error with its rockets, never made it far. Today, it orbits the planet in what scientists call an “eccentric” orbit, similar in shape to a stretched-out rubber band. Because of Cold War secrecy, the researchers aren’t sure how big the spacecraft is. But estimates suggest it’s more than meter (almost 3.5 feet) wide and weighs about 495 kilograms (1,090 pounds).

“It was supposed to escape the sphere of influence of Earth,” said Mutschler, who earned her doctorate in aerospace engineering sciences from CU Boulder in 2022. “It didn’t quite do enough to get out.”

And it’s been slowing down ever since. Mutschler explained that, as Kosmos 482 orbited Earth, it sliced through the upper parts of the atmosphere, experiencing drag much like an airplane flying against the wind. Scientists like her even track tiny changes in the way the spacecraft moves past Earth to improve their simulations, or models, of the conditions in that region of space.

But predicting where the spacecraft will crash is more difficult. In part, that’s because this environment, known as low-Earth orbit, can change a lot. During events called solar storms, for example, the sun releases intense bursts of energy that can cause our planet’s atmosphere to inflate like a balloon. Weather near Earth’s surface can also send disturbances upwards, creating waves and ripples in low-Earth orbit. Pilinski is part of a group at CU Boulder called the Space Weather Technology Research and Education Center (SWx TREC). The center seeks to study the weather in space to better protect satellites in orbit around Earth.

“People who monitor asteroids to see if they will potentially impact Earth actually have an easier job,” Pilinski said. “Those objects would enter at a really steep angle. They’re not skimming part of the atmosphere for days or weeks like this spacecraft.”

Constant noted that understanding space weather is critical as companies across the globe launch more satellites into orbit.

“One collision could spell disaster for everyone else,” he said. “You’d get this cloud of debris flying around, causing other potential collisions—what we call a ‘Kessler event.’”

As for Kosmos 482, Mutschler said the researchers may be able to narrow down their estimates of where the spacecraft will crash about a day ahead of time.

“About a day out, we should know with a reasonable amount of certainty whether there’s going to be a solar storm affecting Earth,” Mutschler said, “or if the atmospheric conditions are going to continue to be quiet.”