Lightning strikes kick off a game of electron pinball in space

When lightning strikes, the electrons come pouring down.

In a new study, researchers at CU Boulder led by an undergraduate student have discovered a new link between weather on Earth and weather in space. The group used satellite data to show that lightning storms on our planet can knock especially high-energy, or “extra-hot,” electrons out of the inner radiation belt—a region of space filled with charged particles that surrounds Earth like an inner tube.

The team’s results could help satellites and even astronauts avoid dangerous radiation in space. This is one kind of downpour you don’t want to get caught in, said lead author Max Feinland.

“These particles are the scary ones or what some people call ‘killer electrons,’” said Feinland, who received his bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering sciences at CU Boulder in spring 2024. “They can penetrate metal on satellites, hit circuit boards and can be carcinogenic if they hit a person in space.”

The study appeared Oct. 8 in the journal Nature Communications.

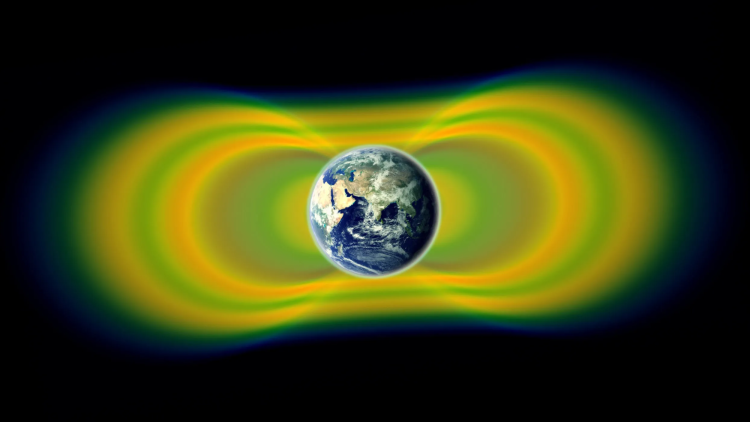

The findings cast an eye toward the radiation belts, which are generated by Earth’s magnetic field. Lauren Blum, a co-author of the paper and assistant professor in the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder, explained that two of these regions encircle our planet: While they move a lot over time, the inner belt tends to begin more than 600 miles above the surface, and the outer belt starts nearly 12,000 miles from Earth. These pool floaties in space trap charged particles streaming toward our planet from the sun, forming a sort of barrier between Earth’s atmosphere and the rest of the solar system.

But they’re not exactly airtight. Scientists, for example, have long known that high-energy electrons can fall toward Earth from the outer radiation belt. Blum and her colleagues, however, are the first to spot a similar rain coming from the inner belt.

Earth and space, in other words, may not be as separate as they look.

“Space weather is really driven both from above and below,” Blum said.

Bolt from the blue

It’s a testament to the power of lightning.

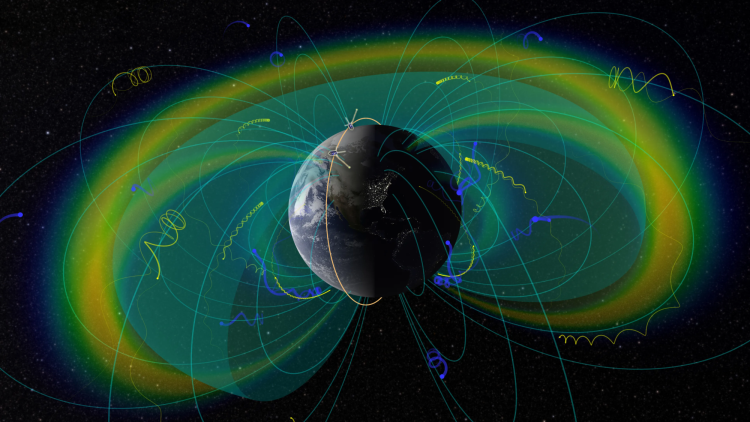

When a lightning bolt flashes in the sky on Earth, that burst of energy may also send radio waves spiraling deep into space. If those waves smack into electrons in the radiation belts, they can jostle them free—a bit like shaking your umbrella to knock the water off. In some cases, such “lightning-induced electron precipitation” can even influence the chemistry of Earth’s atmosphere.

To date, researchers had only collected direct measurements of lower energy, or “colder,” electrons falling from the inner radiation belt.

“Typically, the inner belt is thought to be kind of boring,” Blum said. “It’s stable. It’s always there.”

Her team’s new discovery came about almost by accident. Feinland was analyzing data from NASA’s now-decommissioned Solar, Anomalous, and Magnetospheric Particle Explorer (SAMPEX) satellite when he saw something odd: clumps of what seemed to be high-energy electrons moving through the inner belt.

“I showed Lauren some of my events, and she said, ‘That’s not where these are supposed to be,’” Feinland said. “Some literature suggests that there aren’t any high-energy electrons in the inner belt at all.”

The team decided to dig deeper.

In all, Feinland counted 45 surges of high-energy electrons in the inner belt from 1996 to 2006. He compared those events to records of lightning strikes in North America. Sure enough, some of the spikes in electrons seemed to happen less than a second after lightning strikes on the ground.

Electron pinball

Here’s what the team thinks is happening: Following a lightning strike, radio waves from Earth kick off a kind of manic pinball game in space. They knock into electrons in the inner belt, which then begin to bounce between Earth’s northern and southern hemispheres—going back and forth in just 0.2 seconds.

And each time the electrons bounce, some of them fall out of the belt and into our atmosphere.

“You have a big blob of electrons that bounces, and then returns and bounces again,” Blum said. “You’ll see this initial signal, and it will decay away.”

Blum isn’t sure how often such events happen. They may occur mostly during periods of high solar activity when the sun spits out a lot of high-energy electrons, stocking the inner belt with these particles.

The researchers want to understand these events better so that they can predict when they may be likely to occur, potentially helping to keep people and electronics in orbit safe.

Feinland, for his part, is grateful for the chance to study these magnificent storms.

“I didn't even realize how much I liked research until I got to do this project,” he said.

Other co-authors of the new study included Robert Marshall, associate professor in the Ann and H.J. Smead Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences at CU Boulder, Longzhi Gan of Boston University, Mykhaylo Shumko of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and Mark Looper of The Aerospace Corporation.