5 lessons on improving US education—from high schools that beat the odds

Members of Revere High School's Newcomers Academy hold up a banner celebrating the school's recognition as a School of Opportunity in 2016. Then Prinicipal Lourenço Garcia stands at left. (Credit: RHSl)

Lourenço Garcia remembers spending his long drives home after work in 2010 regretting his life choices.

Garcia had just stepped into a new job as principal of Revere High School in Revere, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. The school was struggling: Nearly half of the roughly 1,900 students were missing 10 or more days of school each year, and suspension rates had hit 7.5%. Garcia and his team, including the school district’s superintendent, were trying to introduce a series of efforts to improve Revere High’s culture, climate and leadership. Those changes included starting a “Newcomers Academy” to support children who had recently emigrated to the United States and a "Freshman Academy" to support middle schoolers transititioning to high school.

Many of the school’s teachers were on board, but Garcia’s team also faced pushback from some educators who were wary of running the school differently than it had been run for decades.

“Ensuring that educators bought into my transformational vision was difficult. As I drove home, I would say to myself, ‘Oh, my god. What have you done?’” Garcia said. “I should have stayed where I was.”

Garcia's stories of school leadership and reform are featured in the new book, Schools of Opportunity: 10 Research-Based Models of Equity in Action. Edited by a trio of CU Boulder researchers, the book walks the halls of nine U.S. high schools that flourished despite the odds—overcoming tough challenges to offer students from a wide range of backgrounds rich and even joyful educational experiences.

Authors hail from CU Boulder and seven other universities alongside nine school leaders.

The effort stems from Schools of Opportunity, a project led by the National Education Policy Center (NEPC) at CU Boulder’s School of Education. For decades, state governments and other entities have judged the success of public schools based largely on a single factor: test scores. From 2015 to 2019, however, the Schools of Opportunity program took a different approach. The project, which is now on hiatus, recognized 52 U.S. public high schools across the country that met a series of 10 alternative criteria—criteria that, according to years of research, can help foster equity in and out of school classrooms.

“These schools show us the diverse ways that public education can be done well,” said Adam York, co-editor of the new book and a research associate in the NEPC. “They each look and feel different, but they all create a welcoming school climate, a space that encourages belonging and positive relationships between staff and students.”

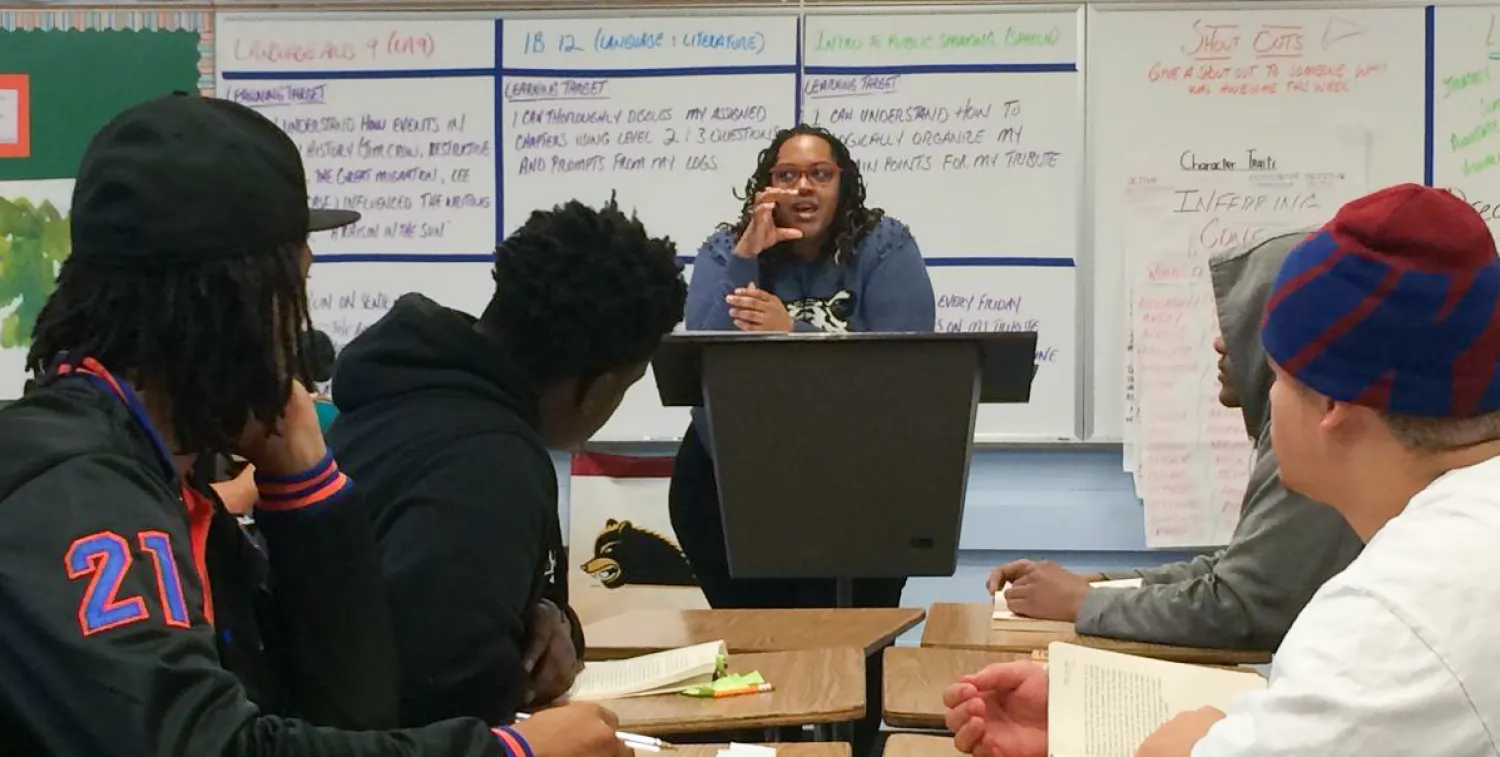

Class is in session at Seattle's Ranier Beach High School. (Credit: RBHS)

Change is possible

The book tells a different story than the increasingly apocalyptic tone of news stories about public education in the United States.

Take Rainier Beach High School. In 2010, the Seattle school was on the brink of closing, with graduation rates at just 46%.

Recognizing schools

From 2015 to 2019, the Schools of Opportunity program selected schools that met a series of 10 criteria, none of which included test scores:

- Broaden and enrich learning opportunities

- Create and maintain a healthy school culture

- Provide more and better learning time

- Use multiple measures to assess student learning

- Support teachers as professionals

- Provide rich, supportive opportunities for students with special needs

- Provide students with additional needed services and supports

- Enact a challenging and supported culturally relevant curriculum

- Build on the strengths of language minority students

- Sustain equitable and meaningful parent and community engagement

Then a new principal named Dwane Chappelle and his team began working to make decisions alongside people from the school’s community. They included a group of mostly-Black parents who billed themselves as “not your mother’s PTA.” The school recruited new staff with input from these community members and launched an International Baccalaureate (IB) program at Rainier Beach.

The deep involvement of the school’s community paid off. By 2018, the school’s graduation rate had hit 89%. It hasn’t dropped below 90% since.

“The schools show us how creative use of time, existing resources, and community partnerships help make change possible,” said Linda Molner Kelley, co-editor of the new book and former director of teacher education and outreach and engagement at CU Boulder.

But it takes a lot of work

Garcia, now assistant superintendent of Equity and Inclusion at Revere Public Schools, knows that better than anyone.

After a lot of long conversations, his team put a group of proposed changes at Revere High to a vote among teachers in 2011. Changes included making class sessions longer so that students could really dig into subjects like algebra and world history. The proposals passed by the thinnest of margins. But within five years of Garcia’s arrival at the school, chronic absenteeism had dropped by almost half while graduation rates climbed by more than 10%.

“It took a lot of talking with people to make sure they understood the value of these transformations,” Garcia said.

His work was also featured in the books Five Practices for Improving the Success of Latino Students and The Human Side of Changing Education.

All students need opportunities to learn

One of the hallmark philosophies of the Schools of Opportunity program was also among its most bold. During its five years of recognizing high schools, the project specifically excluded schools that substantially tracked their students—placing kids into different levels of classes based on their perceived abilities or presumed future life paths, a common practice in many U.S. high schools.

“A school’s best opportunities to learn should not be stratified and rationed,” said Kevin Welner, one of the editors of the new book, director of the NEPC and professor in the School of Education at CU Boulder.

Students of color and other minoritized groups are also much more likely to be placed in lower-track classes, according to research by Welner and others.

“The kids who are placed in low classes typically do not receive the same interesting, rich learning opportunities that students in other classes receive,” Molner Kelley said. “Sadly, they tend to stay in those classes. It’s like a death sentence.”

In the book, Welner and his colleagues tell the story of an institution that tried a different approach called “universal acceleration.” In the late 1990s, South Side High School on New York’s Long Island began removing its lowest-tracked classes, while opening up more advanced classes, such as IB and Advanced Placement (AP) courses, to any student who wanted to join in.

Some parents and educators worried the changes might harm the school’s already high-achieving students. But those fears turned out to be unfounded: By many measures, those high-achievers did even better in the new context, while many of the gaps between them and other students shrank.

Schools need to rethink discipline

For generations, U.S. schools have wielded one tool more than others to address student discipline: suspensions. Schools even use suspensions to punish students who skip class.

Research, however, shows that sending kids home isn’t an effective deterrent against behavioral problems. Schools also tend to suspend students of color much more often than their white peers, said Molner Kelley, who taught English and other subjects in Denver for 11 years.

“The bottom line is that kids need to be in school whenever possible,” she said.

Garcia and his team took that to heart in their own reforms at Revere High. Teachers began training in disciplinary practices inspired by a concept called “restorative justice.” If students get into a scuffle, for example, it can be productive from them to sit in a circle with a teacher and several of their peers to talk over what happened.

In a matter of years, suspension rates fell from 7.5% to 1.4%—all without sacrificing basic safety at the school.

A choir practices at Nebraska's Lincoln High School. (Credit: LHS)

“Restorative justice practice is predicated on the fact that human behavior can be restored,” Garcia said. “You can’t just fault the child when they’re not complying. You have to dig deeper into the factors that are leading to that particular behavior.”

Embracing your local community is key

Mark Larson, a devout fan of Cornhuskers football, grew up in a small town in central Nebraska. He noted that Lincoln High School, where he has worked for 18 years, first as an English teacher and then as an assistant principal and principal, doesn’t look like many people’s stereotype of the Midwest.

A large portion of Larson’s students come from refugee families who have recently settled in the city of Lincoln. Many have had only a few years of formal schooling, and collectively, they speak more than 30 languages at home, including Spanish, Arabic, Swahili and K’iche’, an Indigenous language of Guatemala. While some schools might see these backgrounds as a deficit, Lincoln High has leaned into its diversity.

Among other examples, since 2016 the school has held an annual bilingual career fair, which connects students and their families to employers that value workers who speak multiple languages. The administration also embraces a wide variety of student organizations, including the Joven Noble Latino Leaders Club and the Zomi/Karenni Club for students of Thai and Burmese heritage—alongside groups for skateboarding and cribbage enthusiasts.

It’s not an accident, Larson said, that the school’s mascot are the Links, as in links in a chain.

“Every school in every community has assets that can be leveraged to create an amazing learning environment,” Larson said. “It just takes time to understand what they are.”