NASA’s Orion spacecraft now (finally) heading for the moon. What comes next?

Banner image: NASA's Space Launch System (SLS) rocket sits on a pad days before it carried the Orion spacecraft into space on Nov. 15. Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky

In the early morning hours local time, after months of delays, the most powerful rocket ever built lifted off from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Scientists Jack Burns and Paul Hayne were among the many people across the country who watched the Nov. 15 launch of the Artemis 1 mission, either in-person or through NASA's livestream. The launch marks first stage of an ambitious space program that could one day establish a permanent human presence on the moon.

Burns is a professor in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS) at CU Boulder and leads a NASA-funded center on campus called the Network for Exploration and Space Science. Hayne is an assistant professor in APS and the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) and principal investigator for the Lunar Compact Infrared Imaging System (L-CIRiS). This scientific instrument will touch down on the moon in a few years as part of the Artemis Program.

They spoke about the historic launch and how Artemis will look different than the Apollo Program.

How did you feel watching the rocket launch?

Burns: It was wonderful. I had a chance to go out to Cape Canaveral in June. I was there when they rolled the rocket out for the dress rehearsal of Artemis I, and I was able to get fairly close. It’s a massive vehicle. It’s wonderful to, after all these years of waiting, see our next human-rated space vehicles going to the moon.

Hayne: Seeing a rocket launch, for me, borders on a spiritual experience. That’s not because I'm a scientist or an astronomer. It’s because of the visceral experience of the sight and the sound of something that powerful first lifting off Earth's surface, and then disappearing into space.

What is different between the new Artemis era and the Apollo era of the 1960s and 1970s?

Burns: During Apollo, the reason we went to the moon really didn't have much to do with science or exploration. It was a goal set by President Kennedy to beat the Russians.

This time around, it’s not about beating the Russians. This is about putting footsteps into the solar system to be permanent explorers—not only on the moon, but asteroids, Mars and, eventually, beyond. This is a first step in what we hope will be a sustainable space program. That word sustainable is very important.

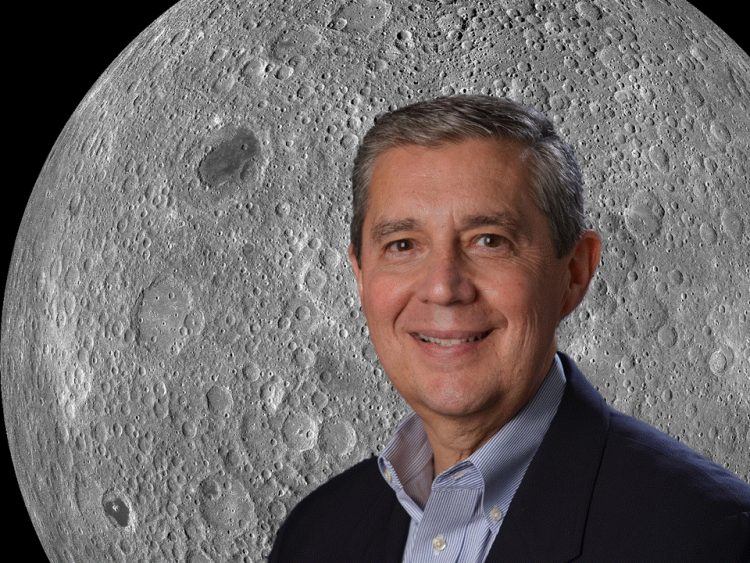

Jack Burns

Paul Hayne

Hayne: There’s still so much we don't know after Apollo. The Apollo landing sites were concentrated on the near side of the moon in very specific locations that were easy to access and communicate with from Earth. That doesn't represent the whole surface of the moon. During the Artemis missions, we’re going to parts of the moon that have never been explored before, and especially the lunar poles.

Why are the poles so important?

Hayne: We often refer to the moon as the solar system’s garbage collector. These areas near the poles sweep up everything in our near-space environment—the same things that are also hitting Earth all the time. There are deep, dark shadows that are so cold that ice and other materials can be trapped in those shadows for billions of years. I want to know what has been collected there.

What can we learn from traveling back to the moon that we didn’t learn from Apollo or decades of robotic missions?

Burns: One of the things I'm excited about as an astronomer is that we're going to be putting radio telescopes on the moon, particularly on the far side.

We’ve seen recently how the James Webb Space Telescope is sticking a toe into the waters of what's called the Cosmic Dawn. That's when some of the first stars and galaxies in existence came into being. Those objects are so faint that even this powerful telescope can only see them so well. With our radio telescopes, on the other hand, we'll be sampling the gas that's around these first stars and galaxies and even further back in time.

How are you involved in this new era of space exploration?

Hayne: I'm involved with a few different missions that are part of the Artemis Program, one of which is going to the lunar south pole. We're going to take infrared pictures of the lunar surface for the very first time to look for places where water might be trapped by those cold temperatures. That will inform where we can send astronauts and robotic rovers to look for and extract the water.

Burns: My students, as one example, are working on building rovers and advancing a field called telerobotics. Telerobotics will allow us to remotely operate a new generation of rovers on the moon that will help astronauts to be much more effective when they're exploring. These mechanical devices will be used to build infrastructure on the moon.

What will be the lasting legacy of the Artemis Program for humanity?

Hayne: Space exploration is something that transcends national borders. It transcends divisions of race and class and identity. We, as a human species, can think of space exploration as an important aspect of our collective identity as the only space-faring species on Earth, and the stewards of this planet.

Burns: Artemis is the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology. The goal for Artemis 3, which will take place in the mid-part of this decade, is to bring the first woman and the first person of color to the moon.

We want to inspire the next generation. We want kids to look up at what NASA is doing and say, “These astronauts look like me. I can do this. I can be part of the space program.”

If the slogan for Apollo was ‘one giant leap for man,’ what’s the slogan of Artemis going to be?

Burns: We’re beyond the “one small step.” Now, we’re into the giant leap. This time we have the technology. We have industry. We have multiple governments that are involved. Now, we're doing this for the long haul. Finally, we will become a space-faring civilization.

CU Boulder Today regularly publishes Q&As with our faculty members weighing in on news topics through the lens of their scholarly expertise and research/creative work. The responses here reflect the knowledge and interpretations of the expert and should not be considered the university position on the issue. All publication content is subject to edits for clarity, brevity and university style guidelines.