A new timeline of Earth’s cataclysmic past

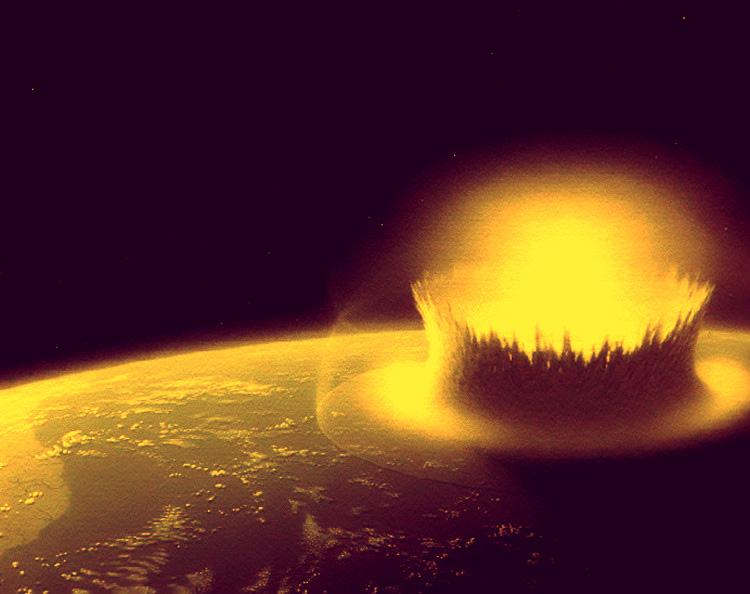

Banner image: An artist's depiction of an early Earth bombarded by asteroids. (Credit: NASA)

Welcome to the early solar system. Just after the planets formed more than 4.5 billion years ago, our cosmic neighborhood was a chaotic place. Waves of comets, asteroids and even proto-planets streamed toward the inner solar system, with some crashing into Earth on their way. These impacts were so violent that they melted the rocks at the planet’s surface.

Now, a team led by CU Boulder geologist Stephen Mojzsis has laid out a new timeline for this violent period in our planet’s history.

In a study published today, the researchers homed in on a phenomenon called “giant planet migration.” That’s the name for a stage in the evolution of the solar system in which the largest planets, for reasons that are still unclear, began to move away from the sun.

Drawing on records from asteroids and other sources, the group estimated that this solar system-altering event occurred 4.48 billion years ago—much earlier than some scientists had previously proposed.

The findings, Mojzsis said, could provide scientists with valuable clues around when life might have first emerged on Earth.

“We know that giant planet migration must have taken place in order to explain the current orbital structure of the outer solar system,” said Mojzsis, a professor in the Department of Geological Sciences. “But until this study, nobody knew when it happened.”

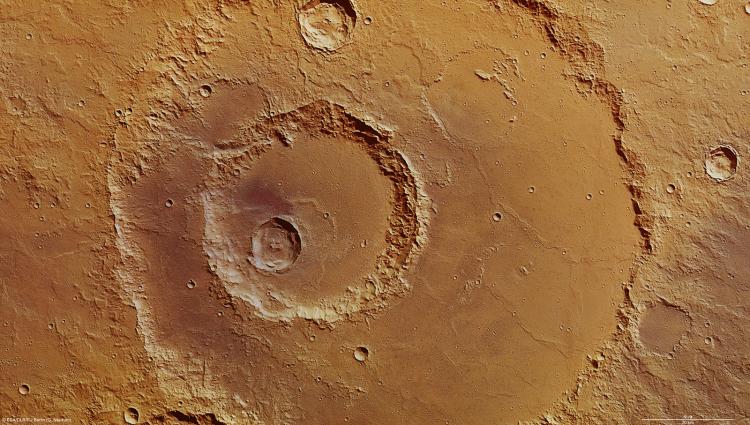

Imbrium Basin

It’s a debate that, at least in part, has its origins in the Apollo space program.

When astronauts landed on the near side of the moon in the late 1960s and early 1970s, they collected a lot of rocks. But those geologic samples were also puzzling: Many seemed to be only 3.9 billion years old, hundreds of millions of years younger than the moon itself.

To explain the seemingly anachronistic rock ages, some researchers suggested that our moon—and Earth—were slammed by a surge of comets and asteroids around that time. They called this spike in impacts, appropriately, the “late lunar cataclysm.”

There was just one problem with the theory, Mojzsis added. When scientists inspected the patterns of craters on the moon, Mars and Mercury they couldn’t find any evidence for such a surge.

“It turns out that the part of the moon we landed on is very unusual,” Mojzsis said. “It is strongly affected by one big impact, the Imbrium Basin, that is about 3.9 billion years old and affects nearly everything we sampled.”

To get around that bias, the researchers decided to step away from the inner solar system. Instead, they compiled the ages from an exhaustive database of meteorites that had crash landed on Earth.

“The surfaces of the inner planets have been extensively reworked both by impacts and indigenous events until about 4 billion years ago,” said study coauthor Ramon Brasser of the Earth-Life Science Institute in Tokyo. “The same is not true for the asteroids. Their record goes back much further.”

The team discovered that, no matter how much they searched, they couldn’t find a single asteroid or chunk of planetary rock that recorded a cataclysmic bombardment event younger than about 4.5 billion years old.

“The 3.9-billion-year ages that dominated the lunar samples were nowhere to be seen in the meteorites,” Brasser said.

For the team, that presented only one possibility: The solar system must have experienced a major bombardment just before that cut-off date. Very large impacts, Mojzsis said, can melt rocks and variably reset their radioactive ages, a bit like shaking an etch-a-sketch.

Planets on the move

And the cause of all that carnage? Mojzsis and his colleagues believe that it comes down to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

He explained that these goliath planets likely formed much closer together than they are today. Using computer simulations, however, his group demonstrated that those bodies started to creep toward their present locations about 4.48 billion years ago.

In the process, they scattered the debris in their wake, sending some of it hurtling toward Earth and its then-young moon.

The bombardment history of the solar system “began with the comets that came screaming into the inner solar system. As they did, they reset the age of the crusts of the Earth, Moon and Mars,” Mojzsis said. “The next wave were planetesimals left over from the formation of the inner planets. The last group to arrive were the asteroids, which continue to leak toward us today.”

The findings, he added, open up a new window for when life may have evolved on Earth. Based on the team’s results, our planet may have been calm enough to support living organisms as early as 4.4 billion years ago. The oldest known fossil shapes today are just 3.5 billion years old.

“The only way to sterilize the Earth completely is to melt the crust all at once,” Mojzsis said. “We’ve shown that this hasn’t happened since giant planet migration commenced.”

Other co-authors on the study include Nigel Kelly, formerly of CU Boulder; Oleg Abramov at the Planetary Science Institute; and Stephanie Werner at the University of Oslo.

The Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) is one of Japan’s ambitious World Premiere International research centers, whose aim is to achieve progress in broadly inter-disciplinary scientific areas by inspiring the world’s greatest minds to come to Japan and collaborate on the most challenging scientific problems. ELSI’s primary aim is to address the origin and co-evolution of the Earth and life.