Ants in Colorado are on the move due to climate change

On a hot summer day in 2022, Anna Paraskevopoulos found herself trekking through forests and shrubs in Gregory Canyon near Boulder, flipping over rocks and logs to look for any signs of ants.

About six decades before that, a team of entomologists had walked on the same trails to record the local ant species, but what Paraskevopoulos saw was very different. Over the past 60 years, climate change has forced certain ant species, unable to tolerate higher temperatures, out of their original habitats in Gregory Canyon.

The resulting biodiversity change could potentially alter local ecosystems, according to Paraskevopoulos, a doctoral student in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at CU Boulder. Her research findings appear April 9 in the journal Ecology.

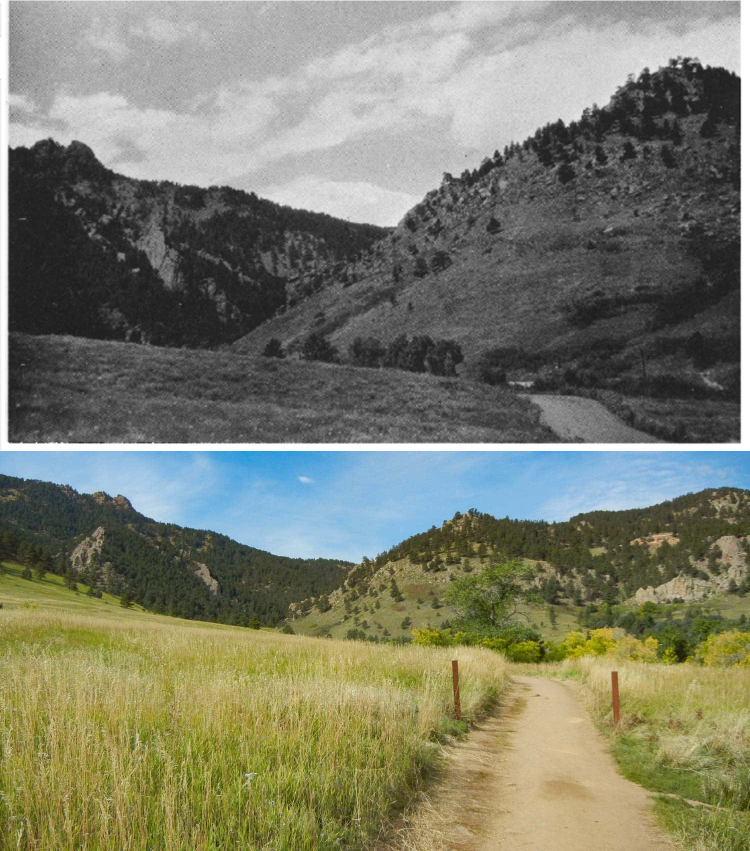

Top: CU Boulder entomologist Robert Gregg and his student John Browne surveyed the ant populations in Gregory Canyon in 1957 and 1958 (Credit: Gregg and Browne/CU Boulder). Bottom: Anna Paraskevopoulos visited the same survey site 60 years later and found significant changes in the ant community. (Credit: Anna Paraskevopoulos/CU Boulder)

Like all insects, ants are ectothermic, meaning their body temperature, metabolism and other bodily functions depend on the environment’s temperature. As a result, ants are sensitive to temperature fluctuations, making them a good marker to study the impact climate change has on ecosystems.

More than six decades ago, CU Boulder entomologist Robert Gregg and his student John Browne surveyed the ant populations in Gregory Canyon. After reading their study, Paraskevopoulos and her team set off to investigate whether the ant community had changed since. The researchers sampled the same survey sites on roughly the same dates between 2021 and 2022 as Browne and Gregg did in 1957 and 1958. The team collected hundreds of ant samples from different parts of Gregory Canyon, each with its own unique environment. For example, the canyon’s north-facing slope is a forest with cool temperatures, dominated by pine and fir trees. The south-facing slope is primarily shrubland, while streams and ditches shape the canyon bottom area.

While the city of Boulder has expanded greatly since the original study, Gregory Canyon has remained a natural environment and largely unaffected by land-use change.

“This gave us an opportunity to study the isolated impacts of climate change. In many other studies, the effect of land use and climate change are often entangled,” Paraskevopoulos said.

While she and her team discovered some ant species that were not recorded previously in the canyon, several other ant species had expanded their habitats and dominated the sites.

The team found while the total number of ant species in Gregory Canyon increased from what was recorded in their 1969 paper, several species had expanded their habitats to a broader region and now dominated the sites. At the same time, some other ants Browne and Gregg observed had become less widespread or were even undetected.

“Across the different environments and habitats in the canyon, we're seeing the composition of ant species becoming more similar,” said Julian Resasco, the paper’s senior author and an assistant professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

The team said 12 ant species have become hard to find compared with six decades ago. Ant species that foraged across a broader range of temperatures are now more widespread, while species that foraged across a narrower range of temperatures have become rare, potentially because they are more sensitive to temperature changes, or are facing increased competition from other ant species that managed to expand their habitats.

Ants the team observed in Gregory Canyon (Credit: Anna Paraskevopoulos/CU Boulder)

An ‘insect apocalypse’

Despite their tiny size, ants are essential ecosystem engineers. They supply soil with air through making tunnels and chambers underground, and accelerate the decomposition of dead plants and animals. Different ant species may play unique roles in the ecosystem, such as dispersing certain types of seeds or preying on specific bugs.

“If the ecosystem has only a single type of ant, it could mean that the animal is only contributing to ecosystem functioning in one way, potentially reducing ecosystem stability,” Paraskevopoulos said.

It remains unclear how changes in ant populations in Gregory Canyon have affected the local ecosystem. But when a species disappears, it affects other organisms that rely on them for food, pollination or pest control, Paraskevopoulos said.

The finding illustrates that changes in ant biodiversity could be happening all around the world in both urban and wild spaces as a result of climate change. Globally, insect populations and diversity are rapidly declining, and the study adds another piece of evidence to what many scientists call an ongoing “insect apocalypse.”

An analysis across 16 studies has shown insect populations declined by 45% in the last four decades. In North America, the monarch butterfly population fell by 90% in the last 20 years. In Colorado, one in five native bumblebees is at risk.

“In response to climate change, species are changing the ranges where they're occurring. Some of them are spreading and becoming winners, while others are crashing and becoming losers. This work helps us understand how those communities reshuffle, which could have implications on how ecosystems function,” Resasco said.