Post-Roe, contraception could be next

Access to contraception in the United States is increasingly under threat, say CU researchers, as some lawmakers interpret the 2022 Dobbs decision as a license to restrict birth control, and a growing effort to stigmatize contraception takes hold on social media.

“We have talked a lot about abortion post-Dobbs, but we don’t talk too much about contraception,” said demographer Amanda Stevenson, assistant professor of sociology at CU Boulder, during a lecture at Science Writers 2023 on Saturday. “The restrictions on contraception have been accelerating in a very similar way to how abortion restrictions accelerated in the past.”

The Boulder and Anschutz campuses co-hosted the national conference of the National Association of Science Writers and the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing. It was attended by more than 600 science journalists, writers and communicators. About 130 science writers attended Saturday’s talk.

There are prominent influencers out there now saying that contraception is harmful to your body, that it makes you attract the wrong kind of man, that it is even deadly.”

—Amanda Stevenson

During the 90-minute panel titled “Abortion and contraception in the post-Dobbs era,” Stevenson and Kate Coleman-Minahan, assistant professor of nursing at CU Anschutz, presented their latest research on how the June 2022 Dobbs decision, which revoked the constitutional right to abortion in the U.S., has impacted policies and lives—and what could come next.

Because abortion is exponentially safer than childbirth, more pregnant people will die as a result of the decision, Stevenson said, and a disproportional number will be women of color.

Her own research estimates that a total abortion ban nationwide would increase maternal mortality by 21% overall and 33% among Blacks. And that’s not counting the roughly 1,000 additional people who would nearly die annually from things like postpartum hemorrhage or preeclampsia.

Youth on the front lines

Young people are already being hit particularly hard by restrictions on abortion, noted Coleman-Minahan.

Many must travel to obtain an abortion, finding themselves in states where the practice is legal, but they must obtain parental consent when they get there.

Colorado, for instance, requires people under age 18 to involve their parents before terminating a pregnancy. Their only other option is to seek approval from a judge via a process called judicial bypass. Up to 13% of the time, they are still denied.

Colorado saw an 89% increase in abortions (about 6,000 procedures) in the first six months of 2023, according to a new report by the Guttmacher Institute.

Between 2020 and 2022, there was a 45% increase in the number of abortions obtained by Colorado young people, and a 110% increase in the number of abortions obtained by young people from out of state, according to new unpublished research presented by Stevenson and Minahan.

The researchers estimate that in 2022, between 20 and 80 Colorado young people were forced to undergo judicial bypass, as were 12 to 25 young people from surrounding states.

“What we know from our research is that these parental involvement laws directly harm young people,” said Coleman-Minahan. “If a young person fears that if they tell their parent they may emotionally or physically abuse them or abandon them, we have evidence to show that they are accurate. Those things do happen.”

Such laws, she said, also reinforce the idea that abortion is morally wrong and dangerous and that young people can’t be trusted.

Stigmatizing contraception

Just as young people and vulnerable communities have been the first to be hit hard by abortion restrictions, they will likely also be the first to be impacted by attacks on contraception, Stevenson said.

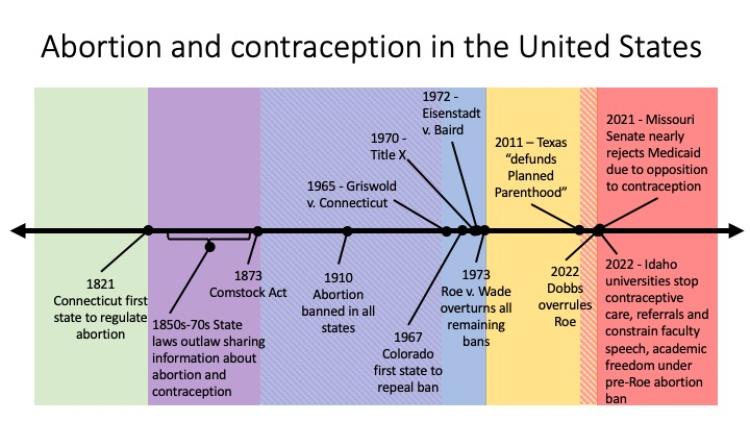

She noted that as far back as the 1850s to 1870s, state laws stigmatized both abortion and contraception as obscene, and outlawed sharing information about them. By 1973, with the passage of Roe v. Wade, such bans had been lifted.

“We are seeing abortion and contraception restricted and stigmatized in tandem again now,” Stevenson said.

“Abortion and contraecption in the United States” timeline. Courtesy of Amanda Stevenson.

For instance, public universities in Idaho have reportedly told staffers not to tell students how to access emergency contraception, because they could be charged with a felony. In 2021, Missouri Republicans tried to ban common forms of birth control from being paid for by the state’s Medicaid program. And some governors and religious organizations have endorsed the idea that some intrauterine devices (IUDs) cause abortions, said Stevenson.

The speakers also expressed concerns about misinformation and stigmatization on social media channels, including TikTok.

“There are prominent influencers out there now saying that contraception is harmful to your body, that it makes you attract the wrong kind of man, that it is even deadly,” said Stevenson.

Meanwhile, an increasingly prominent “pronatalist” (pro-population growth) view that an impending population decline would be disastrous to society also has them worried.

Stevenson pointed to a recent New York Times article declaring that “The world’s population may peak in your lifetime. What happens next?”

“If the idea that low fertility is catastrophic enters the mainstream, we could easily lose the consensus that access to family planning is a social good,” said Stevenson. “This could endanger political support for domestic and international family planning funding and could further embolden legislative efforts to ban specific contraceptive methods.”

Avoiding false balance

During the Q&A, attendees lined up down both aisles to ask whether the Dobbs decision could also impact other forms of reproductive care, like tubal ligations and assistive reproduction (the answer is yes). They also asked what writers like them should be doing.

The answer: Steer clear of the “false balance,” which plagued climate change coverage for so long, and stick to the science.

“It’s important to be very clear when people are talking about their own opinions or moral beliefs versus when they’re talking about science,” said Coleman-Minahan. “Fact check. Just because someone says something is true doesn’t make it balanced.”