Landmark study on history of horses in American West relies on Indigenous knowledge

A mare named Rina with her foal at the Sacred Way Sanctuary in Alabama, which seeks "to educate the world regarding the true history of the horse in the Americas and its relationship with the Indigenous Peoples." (Credit: Sacred Way Sanctuary)

A team of international researchers has dug into archaeological records, DNA evidence and Indigenous oral traditions to paint what might be the most exhaustive history of early horses in North America to date. The group’s findings show that these beasts of burden may have spread throughout the American West much faster and earlier than many European accounts have suggested.

The researchers, including several scientists from CU Boulder, published their findings today in the journal Science.

To tell the stories of horses in the West, the team closely examined about two dozen sets of animal remains found at sites ranging from New Mexico to Kansas and Idaho. The researchers come from 15 countries and multiple Native American groups, including the Lakota, Comanche and Pawnee nations.

“What unites everyone is the shared vision of telling a different kind of story about horses,” said William Taylor, a corresponding author of the study, curator of archaeology at the CU Museum of Natural History, and faculty affiliate of the Center of the American West. “Focusing only on the historical record has underestimated the antiquity and the complexity of Indigenous relationships with horses across a huge swath of the American West.”

For many of the scientists involved, the research holds deep personal significance, added Taylor, who grew up in Montana where his grandfather was a rancher.

“We’re looking at parts of the country that are extraordinarily important to the people on this project,” he said.

The researchers drew on archaeozoology, radiocarbon dating, DNA sequencing and other tools to unearth how and when horses first arrived in various regions of today’s United States. Based on the team’s calculations, Indigenous communities were likely riding and raising horses as far north as Idaho and Wyoming by at least the first half of the 17th century—as much as a century before records from Europeans had suggested.

Groups like the Comanche, in other words, may have begun to form deep bonds with horses mere decades after the animals arrived in the Americas on Spanish boats.

The results line up with a wide range of Indigenous oral histories.

“All this information has come together to tell a bigger, broader, deeper story, a story that natives have always been aware of but has never been acknowledged,” said Jimmy Arterberry, co-author of the new study and tribal historian of the Comanche Nation in Oklahoma.

Study co-author Carlton Shield Chief Gover agreed, noting that the love of horses may be one thing that extends across societies and borders.

“People are fascinated by horses. They’ve grown up with horses,” said Shield Chief Gover, a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma and curator for public anthropology at the Indiana University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. “We can talk to one another through our shared love of an animal.”

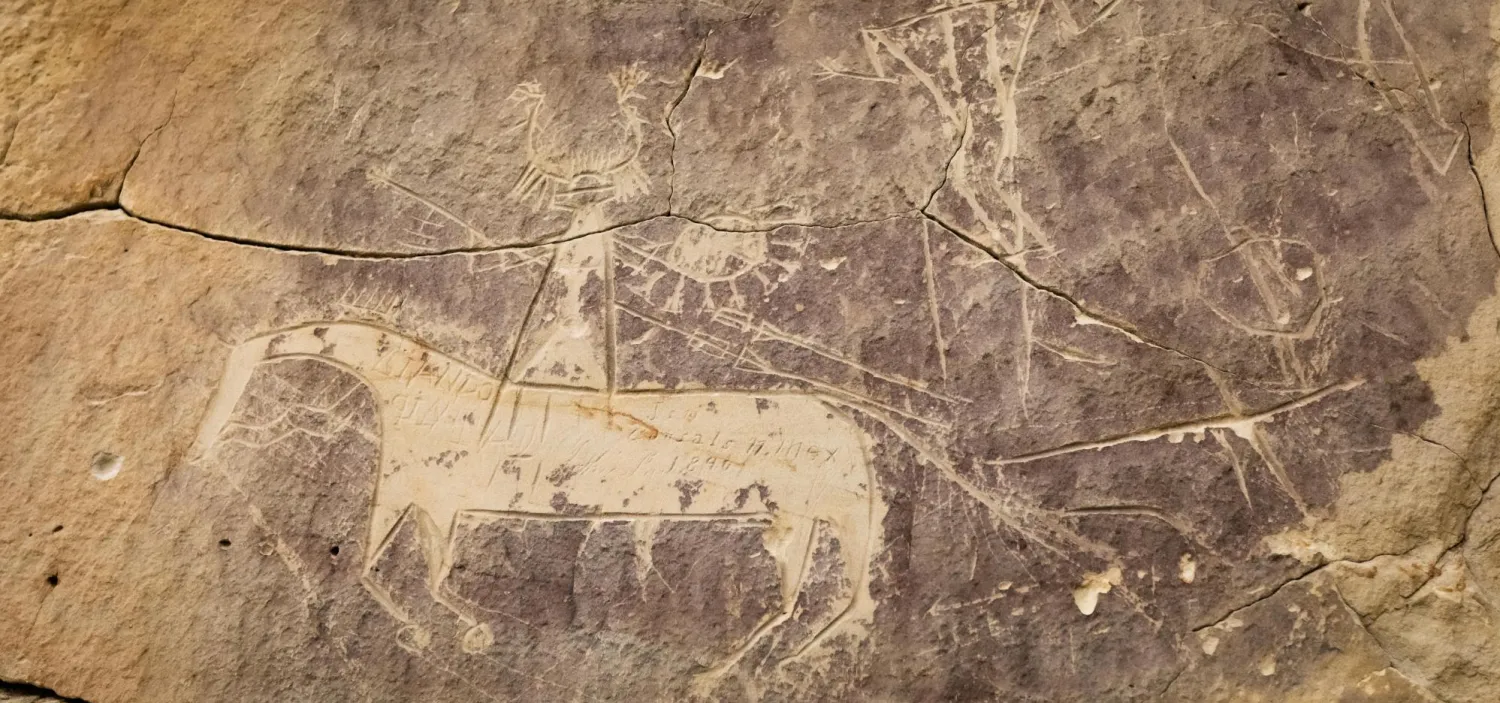

Horse and rider petroglyphs at the Tolar site located in Sweetwater County, Wyoming, likely carved by ancestral Comanche or Shoshone people. (Credit: Pat Doak)

Mud Pony

For many Native American communities that shared love goes a long way back.

The Pawnee, for example, tell the story of “Mud Pony,” a boy who began seeing visions of strange creatures in his sleep.

“He makes these little mud figurines of these animals he sees in his dreams, and, overnight, they become alive,” Shield Chief Gover said. “That’s how you get horses.”

European historical records from the colonial period, however, have tended to favor a more recent origin story for horses in the West. Many scholars have suggested that Native American communities didn’t begin caring for horses until after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. During this event, Pueblo people in what is today New Mexico temporarily overthrew Spanish rule, releasing European livestock in the process.

Taylor, also an assistant professor of anthropology at CU Boulder, and his colleagues didn’t think it fit as an origin story for the relationships between humans and horses in the West: “We thought: There’s something fishy about this story.”

Clues in bone

With funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), they formed an equine dream team that includes archaeologists from the University of Oklahoma and University of New Mexico. Geneticist Ludovic Orlando and Lakota scholar Yvette Running Horse Collin took part from the University of Toulouse in France.

“This research demonstrates how multiple different types of data can be integrated to address the fascinating historical question of how and when horses spread across the West,” said NSF Archaeology program director John Yellen.

Lakota scholar Yvette Running Horse Collin with a horse wearing regalia provided by Sam High Crane (Sicangu Lakota). (Credit: Northern Vision Productions)

Lakota archaeologist Chance Ward inspects a horse skull at the CU Museum of Natural History. (Credit: Samantha Eads)

The researchers began collecting as much data as they could on horses remains from the West. DNA evidence, for example, suggests that most Indigenous horses had descended from Spanish and Iberian horses, with British horses becoming more common in the 18th and 19th Centuries.

Taylor specializes in teasing out the clues hidden in animal bones. Metal bits, for example, leave wear and tear on a horse’s teeth and skull. The archaeologist was especially interested in the remains of a 5- or 6-month-old foal that had been dug up from the Blacks Fork of the Green River in Wyoming in the 1990s. Taylor and his colleagues discovered that the animal had a partially healed skull fracture, potentially from being kicked by another horse. When the animal died of unknown causes, people buried it in a ceremonial fashion alongside three coyotes.

“Our analyses show it was born and raised locally,” Taylor said. “It was cared for, and when that animal passed, there was extraordinary significance to that event.”

The remains of this horse, along with several others from the study, also seemed to date back to around the turn of the 17th Century, decades before the start of the Pueblo Revolt.

How animals like it arrived in Wyoming isn’t clear, but it’s likely that Europeans weren’t involved in their initial transport.

Shield Chief Gover explained that few Indigenous people will be surprised by the results of the study. But the team’s findings may help to illustrate for academic scientists just how important these animals were to the history of Indigenous peoples. The Pawnee, who lived in Nebraska, for example, rode horses on twice-a-year buffalo hunts, traveling farther and faster into the “sea of grass” of the Great Plains. Comanche also galloped on horseback to hunt buffalo, while owning a lot of horses was a sign of wealth.

“I don’t want to diminish the reverence and the respect we have for horses,” Arterberry said. “We see them as gifts the Creator gave us, and, because of that, we survived and thrived and became who we are today.”

Respecting horses

Study co-author Chance Ward, a master’s student in Museum and Field Studies at CU Boulder, would like to see the archaeology community begin to treat those relationships with more respect. He was born and raised on the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota, which is home to four bands of the Lakota Nation. Ward grew up listening to his mother’s childhood stories about riding ponies in the Bear Creek community. His father’s parents started a ranch on the reservation where the family practices rodeo today.

He explained that many researchers don’t handle animal remains with the same care they reserve for cultural objects and human remains.

“They tend to be thrown into a box or bag where they hit against each other and break,” Ward said. “This project is a chance for us as Native people to put our voices out there and take better care of important and sacred animals in museum collections."