Students operate $214M spacecraft. ‘It’s like what you see in the movies.’

Banner image: CU Boulder undergraduate students, left to right, Adrian Bryant and Rithik Gangopadhyay work in the mission operations center for IXPE. (Credit: Casey Cass/CU Boulder)

This month, Kacie Davis got a rare treat for a fan of all things outer space.

The 2020 CU Boulder alumna was one of the first people on Earth to watch as new data streamed from an object called SMC X-1—a type of pulsar, or the collapsed remains of a star that blinks on and off in the night sky.

[video:https://youtu.be/JGij0x0PA_Q]

“It’s a super interesting object,” said Davis, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in astronomy.

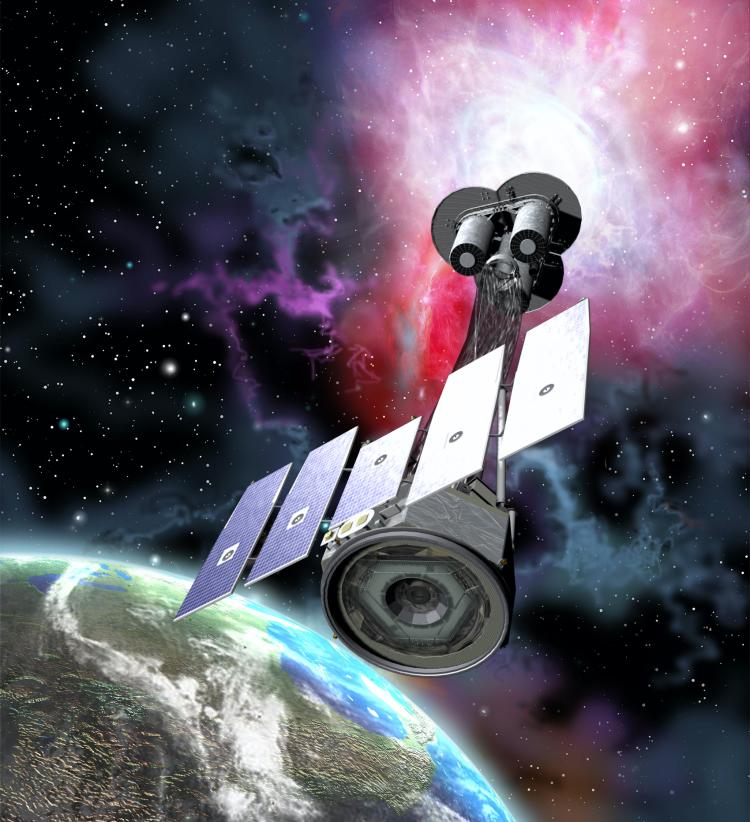

Today, Davis works at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder as a flight controller for a new NASA mission called the Imaging X-Ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE). Over the next two years, Davis and her colleagues will manage the day-to-day mission operations of the spacecraft, which launched on Dec. 9, 2021 Eastern Time from Florida. They’ll send it commands, tell the $214 million satellite where to point and for how long and monitor its health and safety at all hours of the day.

The team had set its sights on SMC X-1 to help calibrate IXPE’s three identical telescope lenses. But as the mission ramps up, it will explore objects like pulsars, supermassive black holes and more in previously unimaginable detail. Davis, at least, can’t wait.

“I learned about IXPE when I was still a student, and I thought, ‘That satellite is going to do the coolest science,’” Davis said. “It’s measuring things that no one has been able to measure before.”

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center leads the overall IXPE mission with the Italian Space Agency as a partner. The Colorado-based Ball Aerospace built the spacecraft.

Over LASP’s more than 70-year history, teams of undergraduates have worked side-by-side with professionals to operate numerous spacecraft and do data processing—from tiny “CubeSats” to NASA’s $600 million planet hunter, the Kepler Space Telescope. For IXPE, the students sit in a mission operations center on the CU Boulder campus complete with rows of glowing monitors that light up every time the spacecraft makes contact with the ground.

“These sorts of missions are an opportunity for students to get involved with a launch and the excitement that goes into it, and that can foster an interest in space that will last a lifetime,” said Jerry Jason, director of mission operations and data systems at LASP.

Mary Wells, a senior studying physics, has certainly caught the space bug.

“It’s like what you see in movies,” said Wells, a command controller on the IXPE team. “There’s a real feeling of being involved in something bigger.”

3…2…1

For Wells and many of her colleagues, that cinematic experience peaked just before midnight in Colorado on Dec. 8.

Most of LASP’s regular staff had gone home for the night, but the atmosphere was still buzzing outside the institute’s main mission operations center on the CU Boulder campus. Nearby, snacks and coffee sat out on a table next to a cake that declared in blue icing, “Go Go Little IXPE.” Inside the control room, Wells and five other operators followed the livestream of the launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on a big screen.

“You could feel the anticipation in the room,” Wells said. “Everybody started clapping when the rocket went up.”

From there, the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carrying IXPE soared over the Atlantic Ocean, making a sharp turn east at the Equator. Just above Kenya, the moment that the IXPE team had been waiting for arrived: The spacecraft separated from its rocket then fanned out four solar panels. About 11:30 p.m. Mountain Time, IXPE sent its first data back to Earth—everything was A-OK.

“When we saw those solar panels deploy, you could hear a sigh in the room,” said Jordan Gage, a senior studying aerospace engineering who was working with Wells in the operations center on launch night. “If the solar panels don’t deploy, your spacecraft won’t work. We would have basically put a rock in orbit.”

Turning on the lights

Gage’s journey began when he was growing up in Greeley, Colorado. His dad used to read him books on astronomy and calculus to put him to sleep when he was an infant. But Gage never thought much about the people who actually drove the multi-million-dollar spacecraft that collect data about the universe.

“I didn’t even realize that was a job until I got into it myself,” he said.

In his freshman year, Gage applied for and joined a cohort of about 20 students who LASP recruited to staff its multiple operations centers. The institute currently operates two more big NASA endeavors, the Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere (AIM) and the Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) missions. The students spent an entire summer learning the ins and outs of spacecraft operations—from how engineers keep components warm in that chilly environment to how satellites turn using thrusters and spinning motors. In all, 23 students currently work in operations at the institute.

In the weeks since the launch, the team has been going through the slow process of commissioning IXPE, flipping on the spacecraft’s various subsystems one by one.

As far as Gage is concerned, “a boring night is a good night.”

Both Gage and Wells said their time at LASP has helped to prepare them for what will come next.

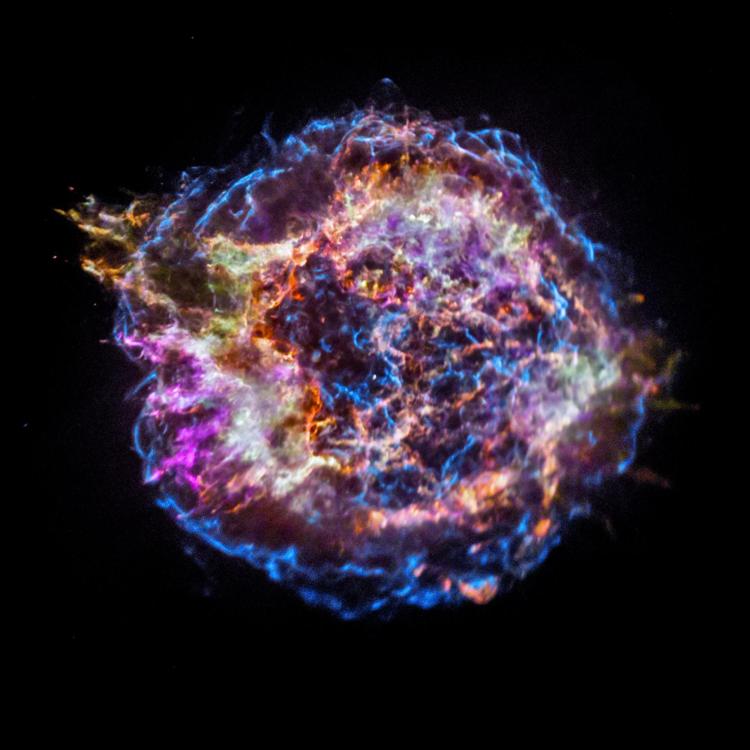

Davis is eagerly watching IXPE’s next steps. On Jan. 11, the spacecraft turned toward its first real scientific target, Cassiopeia A. The team will spend roughly three weeks peering at this object, which looks in NASA images like an iridescent bubble in space. It’s the remnant of a supernova that exploded centuries ago—what Davis called “the beautiful leftovers of the death of a star.”

As Wells put it, “the job is a lot of writing reports and debugging code, which can be taxing. But a lot of it is also commanding the spacecraft and doing other exciting things. It’s really cool to be able to do that as an undergraduate.”