Nuclear war would cause a global famine and kill billions, study finds

This article was adapted from a version published by Rutgers University. Read the original story.

More than 5 billion people would die of hunger following a full-scale nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia, according to a global study that estimates post-conflict crop production led by Rutgers University and CU Boulder climate scientists.

“The data tell us one thing: We must prevent a nuclear war from ever happening,” said Alan Robock of Rutgers, a co-author of the study.

The explosion from a 1953 nuclear test in Nevada. (Credit: Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

Lili Xia at Rutgers is lead author of the research, which appeared today in the journal Nature Food. Co-authors include Charles Bardeen at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and Brian Toon, professor at CU Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) and the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences.

Building on past research, the team calculated how much sun-blocking soot would enter the atmosphere from firestorms that would be ignited by the detonation of nuclear weapons. Researchers calculated soot dispersal from six war scenarios—five smaller India-Pakistan wars and a large U.S.-NATO-Russia war—based on the size of each country’s nuclear arsenal.

“It is astonishing how much smoke can be produced even in a war involving only a few hundred weapons, such as between India and Pakistan,” Toon said.

These data then were entered by Bardeen into the Community Earth System Model, a climate forecasting tool supported by NCAR. The NCAR Community Land Model made it possible for Xia to estimate productivity of major crops (maize, rice, spring wheat and soybean) on a country-by-country basis. The researchers also examined projected changes to livestock pasture and in global marine fisheries.

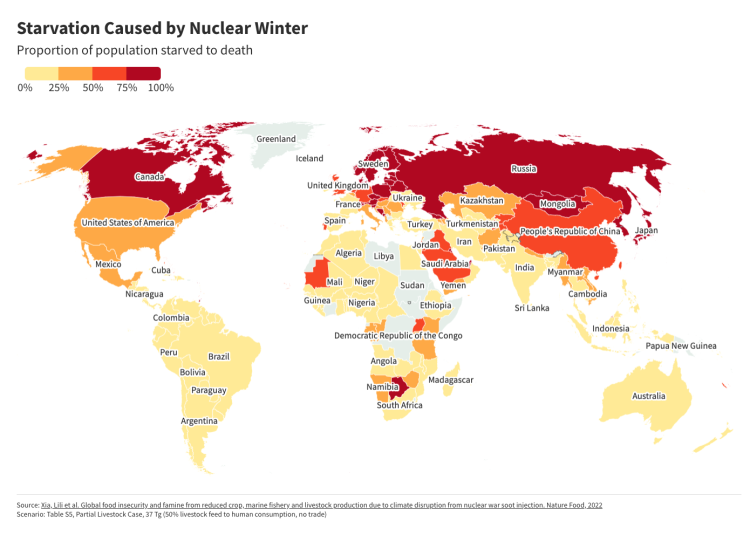

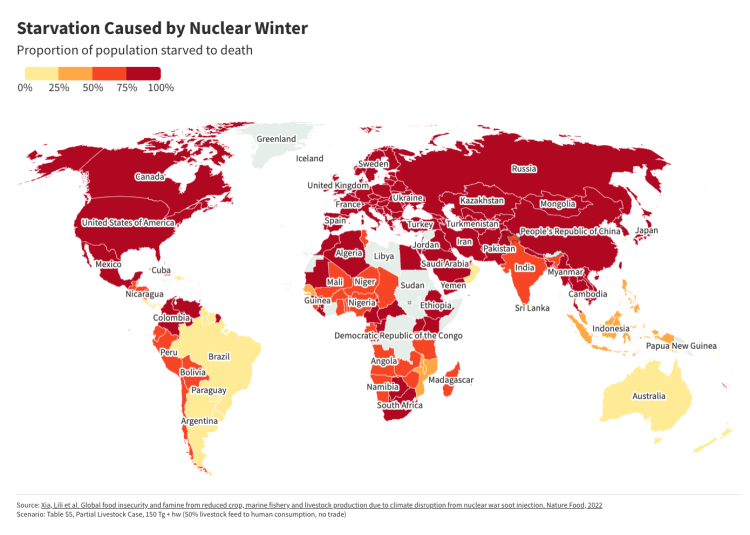

Under even the smallest nuclear scenario, a localized war between India and Pakistan, global average caloric production decreased 7% within five years of the conflict. In the largest war scenario tested—a full-scale U.S.-Russia nuclear conflict—global average caloric production decreased by about 90% three to four years after the fighting.

Crop declines would be the most severe in the mid-high latitude nations, including major exporting countries such as Russia and the U.S., which could trigger export restrictions and cause severe disruptions in import-dependent countries in Africa and the Middle East.

These changes would induce a catastrophic disruption of global food markets, the researchers conclude. Even a 7% global decline in crop yield would exceed the largest anomaly ever recorded since the beginning of Food and Agricultural Organization observational records in 1961. Under the largest war scenario, more than 75% of the planet would be starving within two years.

Preventing a war

Researchers considered whether using crops fed to livestock as human food or reducing food waste could offset caloric losses in a war’s immediate aftermath, but the savings were minimal under the large injection scenarios.

“Future work will bring even more granularity to the crop models,” Xia said. “For instance, the ozone layer would be destroyed by the heating of the stratosphere, producing more ultraviolet radiation at the surface, and we need to understand that impact on food supplies."

Climate scientists at CU Boulder are also creating detailed soot models for specific cities, such as Washington, D.C., with inventories of every building to get a more accurate picture of how much smoke would be produced.

Robock said researchers already have more than enough information to know that a nuclear war of any size would obliterate global food systems, killing billions of people in the process.

“If nuclear weapons exist, they can be used, and the world has come close to nuclear war several times,” Robock said. “Banning nuclear weapons is the only long-term solution. The five-year-old UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons has been ratified by 66 nations, but none of the nine nuclear states. Our work makes clear that it is time for those nine states to listen to science and the rest of the world and sign this treaty.”

Toon added that there’s more that the United States can do to prevent this kind of global catastrophe.

“We need to stop the development of new types of weapons,” Toon said. “We are headed to a situation in which warning times of an attack are becoming so short that artificial intelligence could end up deciding if we go to war. Removing land-based missiles in the U.S. would eliminate a target painted on America, and provide us time to make sure an attack is real before responding, which would lessen the chances of an accidental war.”

Other co-authors of the new study include researchers at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Louisiana State University; the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research; NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies; Columbia Universiy; and Queensland University of Technology.