Preserving corridors between protected lands key to protecting wildlife, study shows

Banner image: Elk in Estes Park, Colorado.

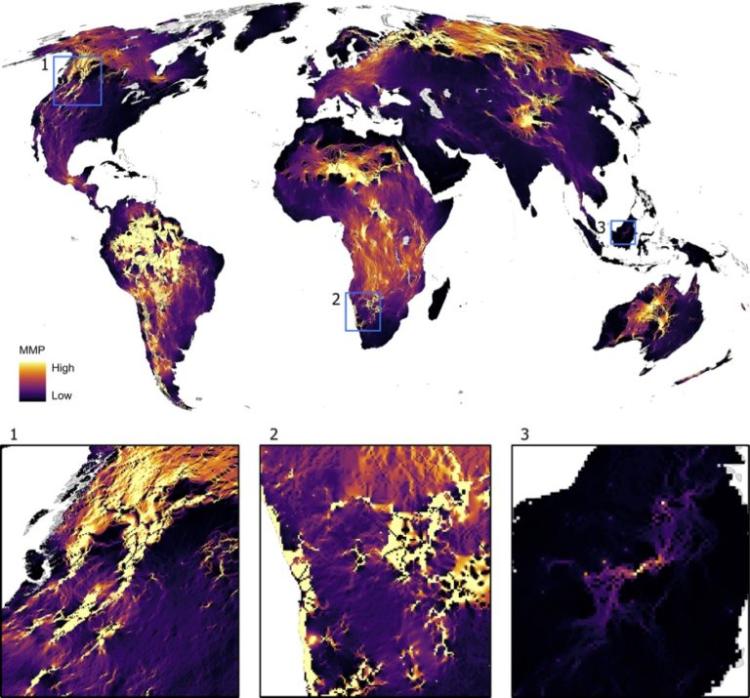

Researchers have created the first global map of where mammals are most likely to move between protected areas, such as national parks and nature preserves. Led by researchers from the University of British Columbia, World Wildlife Fund (U.S.) and CU Boulder, the map also reveals that reducing the human footprint would help mammals move more freely between such areas.

Published June 2 in Science, the study highlights the importance of pathways between protected lands to support biodiversity, genetic diversity within species and their ability to adapt in the face of climate change.

“When you speak to people about connectivity, we often mention a few shining examples like bridges for nature across highways. But the reality is many key areas for the survival of wildlife remain unconnected,” Zia Mehrabi, co-author of the study and assistant professor of environmental studies at CU Boulder.

The researchers used data from a previously published global study of mammal movement in human modified landscapes alongside new models which use theory of electrical circuits to map the world’s critical areas for connectivity. They then used independent GPS data from animals’ collars to verify that movement matched projections.

The United States ranked in the upper 11% of the countries included in the analysis, in terms of how well its protected areas are connected. Some regions do a better job than others: In the western U.S., the Yellowstone to Yukon corridor represents a successful example of movement between protected areas, with the researchers tracking animals such as wolves, elk, coyote, bears and mountain lions. But in the Midwest, large swaths of agricultural farmland hinder the movement of mammals between nature preserves and other protected areas.

Densely populated areas, roads, night lights and other factors can block or prevent animal movement, said Angela Brennan, lead author of the study and a research associate at the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability at the University of British Columbia.

“Even in Colorado, like where I live around Boulder, you have safe havens, but then these are also disrupted by urban areas, by roads and by agriculture,” said Mehrabi.

The researchers projected that reducing the global human footprint by half would increase the potential for mammals to move more freely between protected areas by 28%. And if both the human footprint was reduced and the size of protected areas was increased, connectivity would improve by 43%.

They also looked at critical areas, where the flow of animal movement is particularly important to maintain, representing around 10% of the world’s land. About two-thirds of these were outside of national parks or other types of protected areas, and around 23% were both unprotected and occurred on land suitable for future agricultural use—a large portion of which exists in South America and Africa.

However, 70% of these areas critical to the flow of animal movement overlap with places already identified as being valuable to biodiversity, highlighting areas of synergy for conserving wildlife, said Brennan.

But how can humans practically reduce their footprint to allow animals to move more freely?

That’s the ‘million-dollar question,’ said senior author Claire Kremen, professor in the Department of Zoology and the Institute of Resources, Environment and Sustainability at the University of British Columbia.

Instead of solid corridors of forest or fields, she notes that patches of habitat could act as stepping stones between protected areas, integrated with agriculture or other human development.

“These techniques would mean more habitat, more hiding places, and more ways animals can move between areas,” said Kremen.

This data can also help countries measure their success at protecting biodiversity over time.

“We can't have protected areas everywhere, but we can have incentives for stewards of the land to improve connectivity. Lots of indigenous communities are doing this already,” said Mehrabi. “We need to build incentive structures to allow our landscapes to be more permeable to biodiversity, and to connect landscapes so animals can have the rite of passage.”

This piece was adapted from the University of British Columbia’s press release.

Additional authors on this publication include: R. Naidoo, the University of British Columbia and World Wildlife Fund (U.S.); L. Greenstreet, the University of British Columbia and Cornell University; and N. Ramankutty, the University of British Columbia.