Too many Americans are dying young. This professor is calling for action

Title image: Mourners gather for a candlelight vigil after a school shooting. A new report shows that U.S. youth are more likely to die before age 25 than peers in other wealthy countries, largely due to poverty, violence and lack of social safety nets.

Young people in the United States are far less likely to reach their 25th birthday than their peers in other wealthy countries—and poverty, violence and a lack of social safety nets are largely to blame.

Sociology Professor Richard Rogers

That’s the takeaway from a new 29-page report, Dying young in the United States, co-authored by CU Boulder Sociology Professor Richard Rogers and published by the nonprofit Population Reference Bureau. The multi-year project found that U.S. youth ages 15 to 24 are twice as likely to die than youth in developed countries like France and Germany.

Unintentional injuries, suicides and homicides topped the list of factors cutting young lives short. Meanwhile, the infant mortality rate in the U.S. is as much as three times higher than that of other developed nations.

“This is a bleak report, and it’s tough to read. But it is also a call to action,” said Rogers. “The first step is to acknowledge that we have a problem here, and we document that not just with anecdotes but with hard data.”

The report grew out of a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD)-funded project begun in 2015 aimed at filling what Rogers saw as a glaring research gap.

“There had been a lot of research done on mortality in mid-life, but children and young adults had been largely overlooked,” he said.

A grim picture

He and co-author Robert Hummer, a professor of sociology at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, scoured data from multiple sources, including the National Health Interview Survey, which enabled them to follow 377,000 young people until their 25th birthday or their death, and the Human Mortality Database, which tracks international trends.

Along with collaborators at University of Nevada and Duke University, they have published five studies. The report that compiles them paints a grim picture:

By the numbers

- 60,000 U.S. youth under the age of 25 died in 2019

- 21,000 U.S. infants died in 2019

- 7,580 U.S. youth died of gun violence in 2019

- 2 The U.S. ranks second-worse for child poverty among 35 advanced nations

- 60% Black children and young adults are 60% more likely to die before age 25 than whites

- 30% Mexican American youth are 30% more likely to die before age 25 than whites

Compared with other wealthy countries, the U.S. has the highest death rates for all age groups under age 25. While other peer countries are improving their youth mortality trends, the U.S. is stagnant or worsening. Southern states, including Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Tennessee have the highest youth death rates. And racial disparities are glaring, with Black and Hispanic children at greater risk of dying young.

What’s killing America’s youth?

Whereas adults tend to die from diseases, many young people die from what the report carefully calls “unintentional injuries.”

“‘Accidental’ is a bit of a misnomer,” said Rogers. “It assumes it is all purely by chance, but in many cases, these deaths can be prevented.”

Fatal unintentional injuries from things like poisonings, traffic-related accidents (including bicycle and pedestrian accidents), falls, suffocations and drownings are alarmingly common in the U.S., the report found, accounting for more than one-third of deaths of youth age 15 to 19.

It also notes that 40% of deaths among ages 15 to 19 are suicide or homicide, and the U.S. has a disproportionally high number of firearm-related deaths compared to peer countries.

Socioeconomic disparities are often at the root of the problem, Rogers said.

“In other developed countries, especially European countries, there is less income inequality and there are more safety nets, including social and educational support for parents and better healthcare for families,” Rogers said.

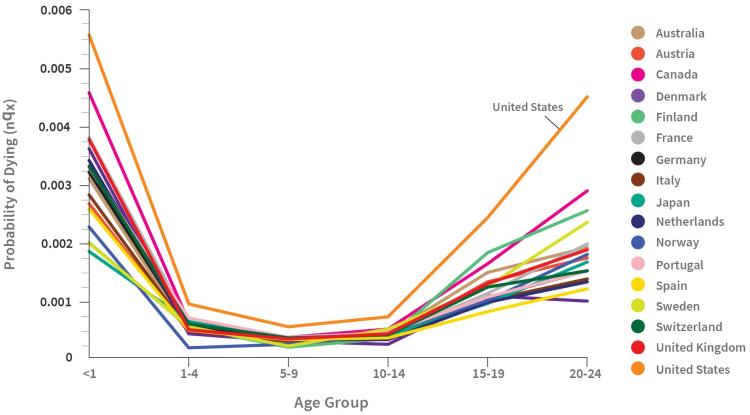

Americans have a higher likelihood of dying in every age group under 25 than their peers in other high-income countries

Probability of Dying in the United States and Peer Countries by Age Group, 2018

Notes: Data for Germany are for 2017.

Source: University of California, Berkeley (USA) and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany), Human Mortality Database, data downloaded Aug. 16, 2021.

U.S. youth living in poverty or with parents who do not have a college degree are at significantly higher risk, while those raised in married, two-parent households—which often benefit from dual incomes and more supervision—are the least likely to die young.

“The number of eyes on a child makes a difference,” said Rogers, noting that simply making sure a child is wearing a seatbelt or a bike helmet or playing in a safe neighborhood can save a life.

The impact of COVID

The data was collected before the emergence of COVID-19, and the authors say it’s too early to fully assess the pandemic’s influence on mortality patterns. But reports of growing mental health problems and substance abuse among children, and parents struggling to find childcare, have them worried.

“More than 140,000 people have lost a parent in this pandemic,” said Rogers. “That will have an impact.”

The authors are calling on lawmakers for “immediate and aggressive action” to reduce child poverty through programs, such as expanded child tax credits and funding for childcare, housing, nutrition and parental education. Many of these policies are contained in the American Families Plan proposed by the Biden administration.

Mental illness and a proliferation of guns in the United States must also be addressed, they said, noting the United States has the highest prevalence of gun ownership and most liberal gun laws among its peer countries.

“A significant number of young lives could have been saved through policies and interventions addressing safety and social and economic inequities, making these losses even more tragic,” said co-author Hummer. “The death of a child or young adult is a tremendous tragedy for parents, for families and for our society.”