How a simple smell test could curb COVID-19 and help reopen the economy

A simple, scratch-and-sniff test could play a key role in curbing the spread of COVID-19, at a fraction of the cost of high-tech tests that are difficult to scale and take longer to return results, new CU Boulder research suggests.

“A lot of people have joked about this idea, but this is the first effort to ask in a rigorous, mathematical way: Could screening for loss of smell actually work?” said author Roy Parker, a professor of biochemistry and director of CU’s BioFrontiers Institute. “We were surprised by how good the results were.”

For the study, Parker and Dan Larremore, an assistant professor of computer science, teamed up with CU Boulder alumnus Derek Toomre, a professor at the Yale School of Medicine who has developed an index-card sized test that interacts with a smartphone app to assess sense of smell.

Credit: Dan Larremore

Studies show that, when simply asked about their symptoms, only about half of people with COVID-19 report loss of smell, or anosmia. But when given a standardized test, with no visual clues to alert them to what they’re smelling and a range of scents chosen to catch even faint loss of smell, that number rises to eight in 10, even among people with no other symptoms.

That’s far more prevalent than fever, which impacts fewer than one in four people with the virus. Anosmia also lasts longer, affecting patients for a week or more while fever may only last a day or two.

While fever is associated with many diseases, loss of smell without a stuffy nose is highly specific to COVID-19, possibly due to the fact the virus tends to enter the body and replicate via ACE2 receptors, which are extremely abundant in cells in nasal passages believed to influence sense of smell.

“Given that we are already broadly screening for temperature at places like hospitals and airports, we asked: ‘What would happen if we started screening for loss of smell instead?’” said Larremore.

A 50-cent test with a big payoff

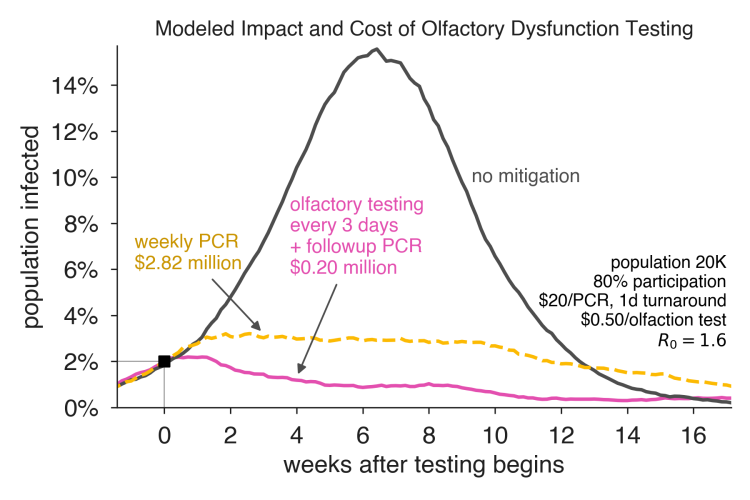

The team used mathematical modeling to predict the effect of smell-testing in several different hypothetical scenarios, including on a college campus of 20,000 people where individuals were tested once a week, every three days or daily; and, at a one-day event where it was used for point-of-entry screening. No students were tested for the research.

In each case, the sniff-test served not as a definitive diagnostic test, but as a screening tool. Those who failed would be referred for a gold-standard PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test in the campus model, or a rapid antigen test for the point-of-entry screening model. Results depended on how early anosmia set in, how common it was and how willing people were to get tested.

But in general, testing for sense of smell every three days worked better than weekly PCR tests in curbing infection—at a fraction of the cost.

For instance, in one modeling scenario, even at the low cost of $20 per PCR test, it would cost nearly $3 million to suppress an ongoing outbreak in a population of 20,000 people using weekly PCR tests. But you could provide smell tests every three days for that same population for $200,000 and catch more infected individuals before they spread the virus.

What if smell-testing was required at the entrance to a big football game or concert?

“We found that you could reduce risk inside by 75% if you tested everybody, and it would only cost about 50 cents each,” Parker said.

One tool in the toolbox

Toomre, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry from CU Boulder in 1990, recently launched a company called usmellit to commercialize the test. It features five scratch-and-sniff squares and asks users to identify the five scents and enter the answer into their smartphone. It either tells them they passed or instructs them to get a COVID-19 test.

usmellit, developed by CU Boulder alumnus Derek Toomre

This particular test is not commercially available yet, but Toomre applied for Emergency Use Authorization from the Food and Drug Administration in October. Once approved, he said the company could swiftly ramp up production to potentially hundreds of millions of tests per week, with one card donated to a charitable nonprofit for every one purchased.

“We hope that it would allow for a fast and easy test that anyone can take anywhere and can be applied to anyplace that is using temperature screening as an inexpensive way to help avoid shutdowns, keep businesses open and decrease the terrible human toll,” he said.

The paper has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, and the authors caution that more research, testing the idea in a broad community, is necessary before such tests could be broadly rolled out as a screening tool.

But they are optimistic.

“This is not a silver bullet,” said Larremore. “But it could be another useful tool in our repertoire of tools for getting a handle on this virus."