Researchers develop dustbuster for the moon

Dust sticks to the boots of Apollo 17 astronaut and geologist Harrison "Jack" Schmitt in 1972. (Credit: NASA)

A team led by the University of Colorado Boulder is pioneering a new solution to the problem of spring cleaning on the moon: Why not zap away the grime using a beam of electrons?

The research, published recently in the journal Acta Astronautica, marks the latest to explore a persistent, and perhaps surprising, hiccup in humanity’s dreams of colonizing the moon: dust. Astronauts walking or driving over the lunar surface kick up huge quantities of this fine material, also called regolith.

“It’s really annoying,” said Xu Wang, a research associate in the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder. “Lunar dust sticks to all kinds of surfaces—spacesuits, solar panels, helmets—and it can damage equipment.”

So he and his colleagues developed a possible fix—one that makes use of an electron beam, a device that shoots out a concentrated (and safe) stream of negatively-charged, low-energy particles. In the new study, the team aimed such a tool at a range of dirty surfaces inside of a vacuum chamber. And, they discovered, the dust just flew away.

“It literally jumps off,” said lead author Benjamin Farr, who completed the work as an undergraduate student in physics at CU Boulder.

The researchers still have a long way to go before real-life astronauts will be able to use the technology to do their daily tidying up. But, Farr said, the team’s early findings suggest that electron-beam dustbusters could be a fixture of moon bases in the not-too-distant future.

Spent gunpowder

The news may be music to the ears of many Apollo-era astronauts. Several of these space pioneers complained about moon dust, which often resists attempts at cleaning even after vigorous brushing. Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, who visited the moon as a member of Apollo 17 in 1972, developed an allergic reaction to the material and has said that it smelled like “spent gunpowder.”

The problem with lunar dust, Wang explained, is that it isn’t anything like the stuff that builds up on bookshelves on Earth. Moon dust is constantly bathed in radiation from the sun, a bombardment that gives the material an electric charge. That charge, in turn, makes the dust extra sticky, almost like a sock that’s just come out of the drier. It also has a distinct structure.

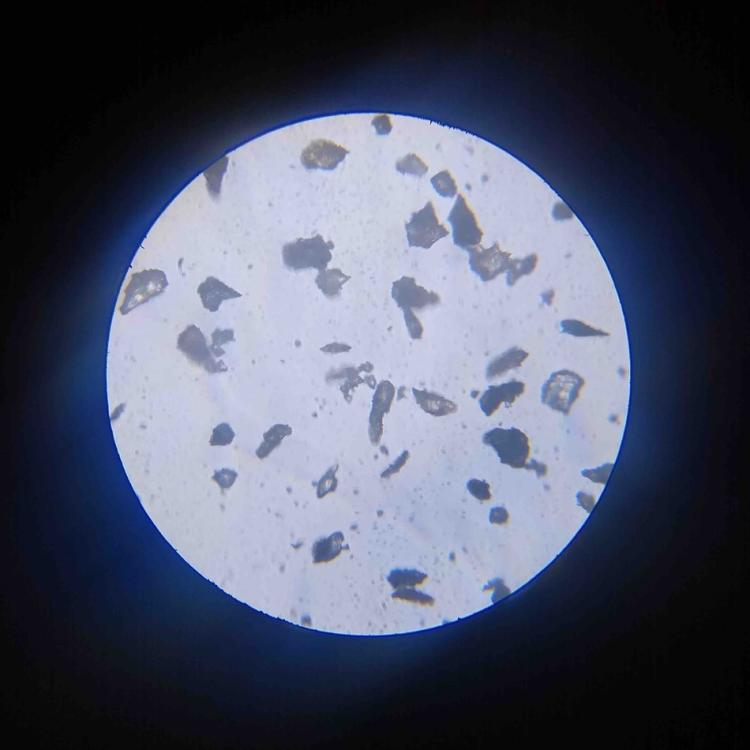

Top: A microscope view of NASA-manufactured lunar "simulant" designed to resemble moon dust; bottom: A vacuum chamber on the CU Boulder campus. (Credits: IMPACT lab)

“Lunar dust is very jagged and abrasive, like broken shards of glass,” Wang said.

The question facing his group was then: How do you unstick this naturally clingy substance?

Electron beams offered a promising solution. According to a theory developed from recent scientific studies of how dust naturally lofts on the lunar surface, such a device could turn the electric charges on particles of dust into a weapon against them. If you hit a layer dust with a stream of electrons, Wang said, that dusty surface will collect additional negative charges. Pack enough charges into the spaces in between the particles, and they may begin to push each other away—much like magnets do when the wrong ends are forced together.

“The charges become so large that they repel each other, and then dust ejects off of the surface,” Wang said.

Electron showers

To test the idea, he and his colleagues loaded a vacuum chamber with various materials coated in a NASA-manufactured “lunar simulant” designed to resemble moon dust.

And sure enough, after aiming an electron beam at those particles, the dust poured off, usually in just a few minutes. The trick worked on a wide range of surfaces, too, including spacesuit fabric and glass. This new technology aims at cleaning the finest dust particles, which are difficult to remove using brushes, Wang said. The method was able to clean dusty surfaces by an average of about 75-85%.

“It worked pretty well, but not well enough that we’re done,” Farr said.

The researchers are currently experimenting with new ways to increase the cleaning power of their electron beam.

But study coauthor Mihály Horányi, a professor in LASP and the Department of Physics at CU Boulder, said that the technology has real potential. NASA has experimented with other strategies for shedding lunar dust, such as by embedding networks of electrodes into spacesuits. An electron beam, however, might be a lot cheaper and easier to roll out.

Horányi imagines that one day, lunar astronauts could simply leave their spacesuits hanging up in a special room, or even outside their habitats, and clean them after spending a long day kicking up dust outside. The electrons would do the rest.

“You could just walk into an electron beam shower to remove fine dust,” he said.

Other coauthors on the new research include John Goree of the University of Iowa and Inseob Hahn and Ulf Israelsson of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.