Inside Steve Bannon’s ‘War for Eternity’

From left to right: Benjamin Teitelbaum, former Trump speechwriter Darren Beattie, an unidentified guest, Steve K. Bannon, three Brazilian guests, Brazilian presidential adviser Olavo de Carvalho, Gerald Brandt. (Credit: Josias Teófilo)

On a June morning in 2018, Benjamin Teitelbaum found himself in what might seem an unlikely position for a university professor who studies Swedish folk music.

Far from his instrument-filled home in the Boulder foothills, he sat in a swanky top-floor penthouse on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Across from him, fresh out of the shower and eager to chat, sat ousted Trump political strategist Steve Bannon.

Teitelbaum pressed play on his hand-held recorder, looked across the table and asked a single question he’d been trying to ask Bannon for over a year:

“Are you a Traditionalist?” he asked, referring to a little-known spiritual sect rooted in notions that time is cyclical, the “dark age” is upon us, and Aryan males inhabit the top of an ancient cosmic hierarchy.

That simple question kick-started a year-long odyssey in which Teitelbaum, an ethnomusicologist-turned-alt-right scholar, recorded more than 20 hours of taped interviews with Bannon and traveled the globe getting to know his Traditionalist contemporaries.

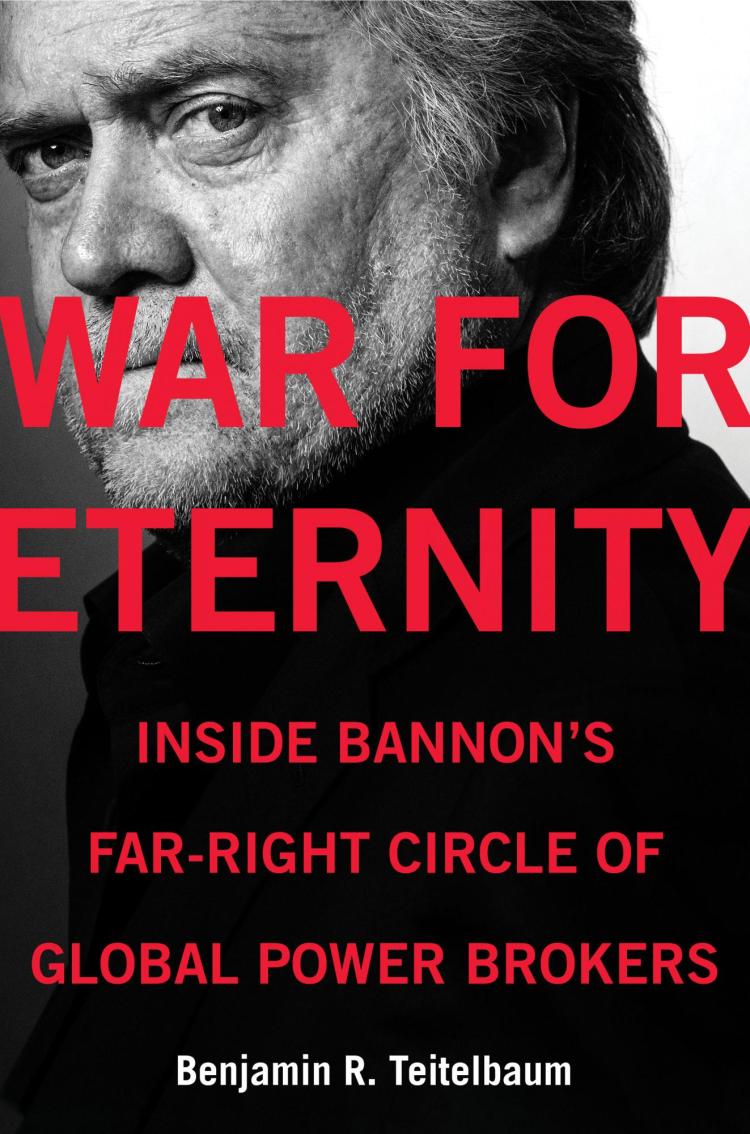

The resulting new book, War For Eternity: Inside Bannon’s Far-Right Circle of Global Power Brokers, out this week, sheds light on a bizarre ultraconservative ideology shared by advisors to populist leaders in Brazil, Russia and Hungary—and the surprising political power they may be wielding.

“A lot of people assume these moves toward closing borders and hostilities toward multiculturalism and immigration are grounded in racism. My book doesn’t refute that, but it suggests that is not, by any means, the whole story,” said Teitelbaum.

From ethnomusicologist to alt-right scholar

The son of a Jewish father and Christian Swedish mother, Teitelbaum grew up playing the nyckelharpa—a traditional Swedish folk instrument—and studying the culture behind music.

Benjamin Teitelbaum

In graduate school, that interest drew him to Sweden, where the music he studied also happened to be the object of admiration by a growing segment of the extreme right.

“I saw music as an often neglected window into the way that people saw themselves and the world around them,” he said, noting that when he said he was a musicologist, people tended to let their guard down. “It made them more comfortable speaking with me. They assumed music isn’t all that serious of a subject to study.”

Teitelbaum soon found himself attending protests and festivals and cultivating a close rapport with leaders in the white identity movement—a tactic he at times found uncomfortable and has sometimes been criticized for but firmly defends as integral to his research.

In the course of his ethnographic study of white identity culture, he began to hear about a strain of far-right thought known as Traditionalism.

“I would write about it and teach it mainly because it was just so off the wall,” said Teitelbaum, also an affiliate faculty member in international affairs. “My students referred to it as Dungeons and Dragons for racists.”

Then, in 2016, press reports began to surface suggesting that Bannon, then chief strategist to President Donald Trump, was reading the works of Traditionalist writer Julius Evola.

“I was absolutely floored to learn that someone with real political power was being influenced by this,” he said. “I spent the next year trying to get in touch with him and when I got the slightest bit of receptiveness I hopped on a plane and showed up at his place.”

Traditionalism 101

Teitelbaum defines Traditionalism as “a bizarre underground and philosophical school with an eclectic if miniscule following.” It hinges on philosophical truths that borrow from many faiths, from Hinduism and Zoroastrianism to the pre-Christian pagan religions of Europe.

Different schools of Traditionalists share different beliefs (Bannon has distanced himself from the notion that white Aryan males from the North belong to a priestly caste, Teitelbaum notes).

But many agree on two key themes: that time cycles through four distinct ages: the golden, silver, bronze and dark age; and that “modernism” as we know it—with its by blurred national borders, multiculturalism and increasing immigration—must go in order for the spiritual advance of humanity to occur.

“Traditionalism declares modern society meaningless on the grounds that our states and communities are increasingly based only on economics or bureaucratic formality rather than culture and spirit,” he writes. “The only bit of improvement for human society comes when the dark age explodes into chaos and the cycle restarts itself at the beginning of the golden age.”

Through exclusive interviews in esoteric salons and secret meetings with far-right thinkers from rural Virginia to Budapest, Teitelbaum makes the case that this obscure worldview is having a notable impact on global politics today.

He notes that Aleksandr Dugin, who is heavily influenced by Traditionalist works, has had the ear of the Kremlin and Olavo de Carvalho, another Traditionalist thinker, serves as an advisor to Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.

He also offers an intimate biography of Bannon, who he says is anything but washed up, with dozens of projects in the works and a recently launched podcast in which he discusses the coronavirus pandemic.

“He thinks that what we are going through today is a rebuke of liberalism and globalism and that societies that are able to fortify their borders and act as local collectives will be rewarded,” Teitelbaum said.

With his year of intrigue and travel behind him and his book hitting the shelves, he hopes his book will open people’s eyes to a worldview they likely didn’t know existed.

“Some of these actors who are trying to shape the future of our society are thinking in terms that are so foreign to most educated, thoughtful and engaged people,” he said. “It is time we start paying attention.”