$130 million space mission to monitor Earth’s energy budget

CU Boulder will soon play a major role in measuring the withdrawals from Earth’s energy bank account.

This week, NASA announced that it has given the green light to Libera, a new space mission that will record how much energy leaves our planet’s atmosphere on a day-by-day basis—data that can provide crucial information about how Earth’s climate is evolving over time.

Peter Pilewskie, a professor at CU Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP), will lead the development of this nearly $130-million mission.

“This highly innovative instrument introduces a number of new technologies such as advanced detectors that will improve the data we collect while maintaining continuity of these important radiation budget measurements,” said Sandra Cauffman, acting director of NASA’s Earth Science Division, in a statement.

LASP Director Daniel Baker added that the mission builds on the center’s seven decades of work to better understand the relationships between Earth and its sun—and the implications for humans on the ground.

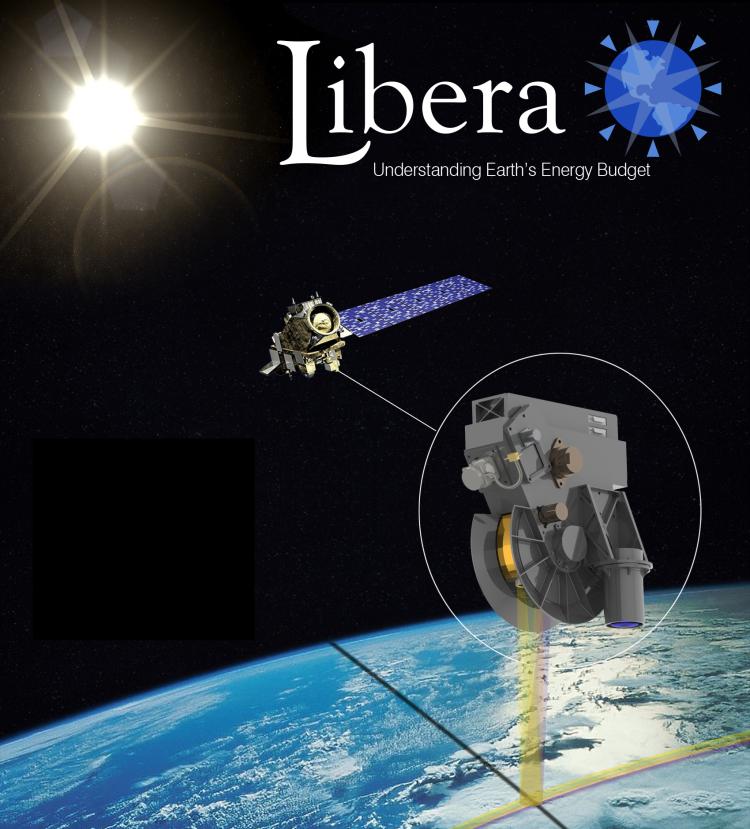

A graphic of what the Libera instrument might look like onboard NASA's Joint Polar Satellite System-3. (Credit: Martha Lageschulte, Ball Aerospace)

“Libera is a major new step in that long journey,” Baker said. “The Libera team will bring the energy, innovation and cost-effectiveness of an academic-led team to address a fundamental question in space and Earth science. LASP is proud to be leading the way in this fascinating endeavor.”

Libera is a partnership between CU Boulder, Ball Aerospace, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), all based in Colorado, and Utah State University.

Getting the balance right

The mission also builds on decades of observation from NASA’s suite of Clouds and the Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES) instruments. In Roman mythology, Libera is the daughter of the goddess Ceres.

The mission focuses on understanding the flow of energy out of the planet and how it changes over time, said Pilewskie, also of the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at CU Boulder.

He explained that every minute, Earth absorbs a huge amount of energy from the sun. At the same time, our planet also emits and reflects energy back into space. Just like the difference between deposits and withdrawals determines how much money you have in your bank account, “the balance of those two processes over time tells us about the state of climate,” Pilewskie said. “If there’s an imbalance, the climate changes.”

A lot of things can contribute to such an imbalance, he added—from shifts in the ice that floats in the oceans to changes in cloud cover and, of course, how much greenhouse gases humans inject into the atmosphere.

LASP, through its efforts on NASA missions like the Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE) and Total and Spectral Solar Irradiance Sensor (TSIS-1), has been measuring the deposits side of that equation for years. Now, the research center is turning its attention to the withdrawals.

“In many ways, this is an Earth analog of what we’ve done with solar radiation measurements,” Pilewskie said. “We’re turning those instruments back at Earth and measuring the full energy budget of radiation that’s leaving the planet.”

To take those incredibly-precise measurements, Libera employs an innovative detector called an electrical substitution radiometer. It uses materials called carbon nanotubes to detect a broad spectrum of radiated energy with high accuracy. The instrument will ride onboard a planned NASA and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) satellite called the Joint Polar Satellite System-3 (JPSS-3). JPSS-3 and Libera are slated to launch in 2027.

Pilewskie and his colleagues can’t wait to get started.

“We’re confident that the innovations that Libera provides will extend these long-running measurements and improve our ability to monitor changes in the Earth system,” he said. “We’re excited to get working on this.”