Behold the super-puffs: Planets as fluffy as cotton candy

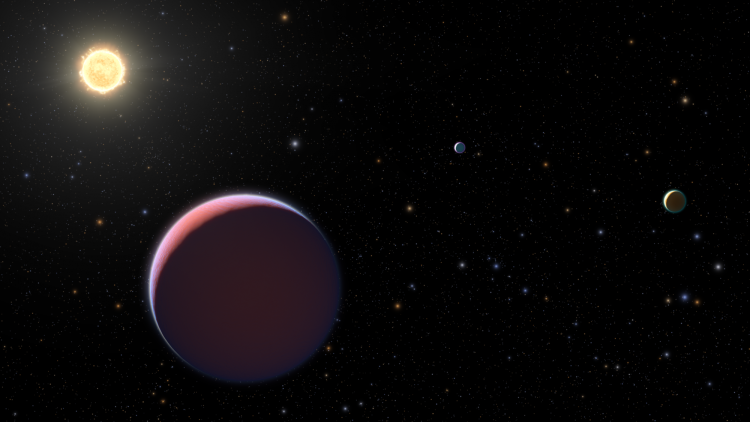

Photo illustration

Meet what may be the largest carnival delights known to science: the “super-puff” worlds of the Kepler 51 star system.

As their confectionary name suggests, these planets are as lightweight as cotton candy—literally. The fluffy globes are the lowest density exoplanets ever discovered beyond Earth’s solar system. And Jessica Libby-Roberts, a graduate student in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS) at the University of Colorado Boulder, wants to learn more about them.

“They’re very bizarre,” said Libby-Roberts, who led an effort to take the closest look yet at the planets.

In a study that will appear in The Astronomical Journal, she and her colleagues set out to uncover the components that make up the exoplanets’ atmospheres—and to provide new clues around how such low-density planets may have formed in the first place.

“This is an extreme example of what’s so cool about exoplanets in general,” said Zachory Berta-Thompson, an assistant APS professor and a coauthor of the new research. “They give us an opportunity to study worlds that are very different than ours, but they also place the planets in our own solar system into a larger context.”

Candy shell

Berta-Thompson explained that super-puff planets are relatively rare in the galaxy—fewer than 15 have been recorded so far.

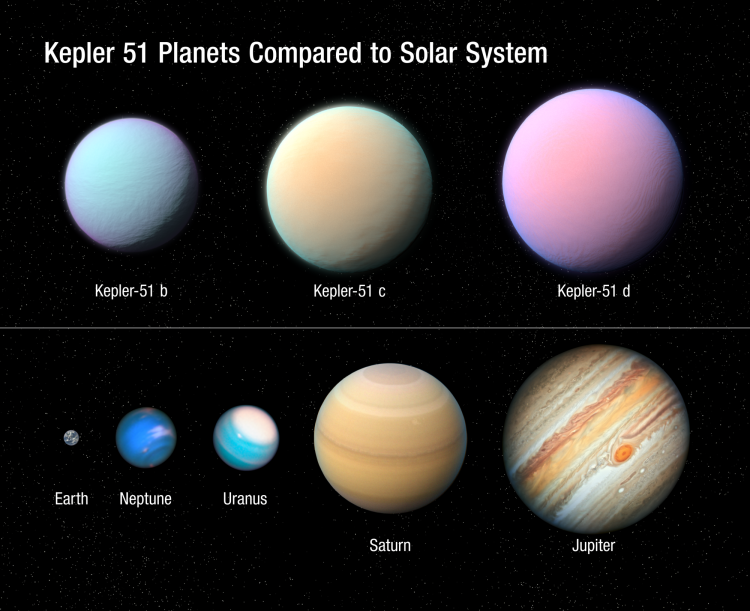

Kepler 51’s trio, which was first described in 2014, take planetary puffiness to new levels. Their discovery was “straight-up contrary to what we teach in undergraduate classrooms,” Berta-Thompson said.

To get a closer look, he and Libby-Roberts used the Hubble Space Telescope to zoom in on the Kepler 51 star system. It’s located about 2,400 lightyears, or thousands of trillions of miles, from Earth and is a relative youngster at 500 million years old.

The team’s first question: Were these planets for real?

The researchers developed new estimates for the trio’s masses and densities. And, sure enough, all three planets had a density less than 0.1 grams per cubic centimeter of volume—almost identical to the sweet pink treats you can buy at any fairground, Libby-Roberts said.

“We knew they were low density,” she said. “But when you picture a Jupiter-sized ball of cotton candy—that’s really low density.”

The researchers also wanted to look deeper, using Hubble to peer into the planets’ atmospheres. That’s when they ran into trouble: The atmospheres of the super-puffs weren’t transparent at all. Instead, they appeared to be shrouded by a high-altitude layer of something opaque.

“It definitely sent us scrambling to come up with what could be going on here,” Libby-Roberts said. “We expected to find water, but we couldn’t observe the signatures of any molecule.”

Using computer simulations and other tools, the group theorized that the Kepler 51 planets are mostly hydrogen and helium by mass—lightweight gases that give these worlds their puffiness. That hydrogen and helium, however, also seems to be covered up by a thick haze made up of methane.

In that sense, the exoplanets could resemble Saturn’s moon Titan, which is surrounded by a similarly carbon-rich smog.

“If you hit methane with ultraviolet light, it will form a haze,” Libby-Roberts said. “It’s Titan in a nutshell.”

Shrinking volume

The researchers made another observation, too—one that indicated that these fluffy planets might not be so strange after all.

Both Kepler 51 planets seemed to be shedding gas at a rapid pace. The innermost of the three worlds, for example, dumps an estimated tens of billions of tons of material into space every second. The group calculated that if that trend continued, the planets could shrink considerably over the next billion years, losing their cotton candy-like puffiness.

In the end, they might wind up looking more like a common class of exoplanets called “mini-Neptunes.”

“People have been really struggling to find out why this system looks so different than every other system,” Libby-Roberts said. “We’re trying to show that, actually, it does look like some of these other systems.”

Berta-Thompson agreed: “A good bit of their weirdness is coming from the fact that we’re seeing them at a time in their development where we’ve rarely gotten the chance to observe planets.”

Other coauthors on the new study include researchers from the University of Amsterdam, Princeton University, the University of Texas at Austin, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, California Institute of Technology, University of Chicago, University of California, Santa Cruz, Arizona State University and Netflix.