75 years after internment, librarians give voice to Japanese and Japanese American history

The hallways under CU Boulder’s Norlin Library are lined with rows and rows of nondescript gray boxes. It’s not the most scenic spot on campus, but the university’s 101 year-old archives can be a glimpse into different worlds and times.

Many of those gray boxes offer a window into the lives of Japanese and Japanese Americans on campus around World War II and Japanese incarceration in the United States.

While University Libraries collections from this era are fairly comprehensive, there are gaps in the record. The CU Japanese and Japanese American Community History Project seeks to change that.

Get involved

Archivists are actively looking for oral histories and other historical documentation. Reach out if you'd like to share materials or get involved.

The College of Music is bringing No-No Boy, named for the Japanese Americans who were ordered to live in internment camps, to campus for a weeklong residency starting Oct. 7.

Adam Lisbon, Japanese and Korean studies librarian, and Megan Friedel, head of archives, embarked on the project in August. They’re conducting interviews, digitizing records and collecting new archival materials. By design, the project aligns with the 75th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt suspending Japanese incarceration in the United States.

“We’re using that as a jumping off point for talking about and collecting information about Japanese and Japanese American history on campus,” said Friedel. “Not just during World War II, but from the first Japanese American student to the present day.”

Lisbon taught English in Japan for four years before coming to CU Boulder. In Colorado, he found community with others who shared a connection to the country, including Japanese and Japanese American groups.

He was quick to realize the potential for preserving more of that community’s history at CU Boulder and throughout the region. He remembers being concerned during conversations with Japanese American friends who had no specific plans for preserving family heirlooms.

“It’s a chance for us to work with that community to talk about archiving and preserving their history,” said Lisbon. “We want to work with the community in a larger framework.”

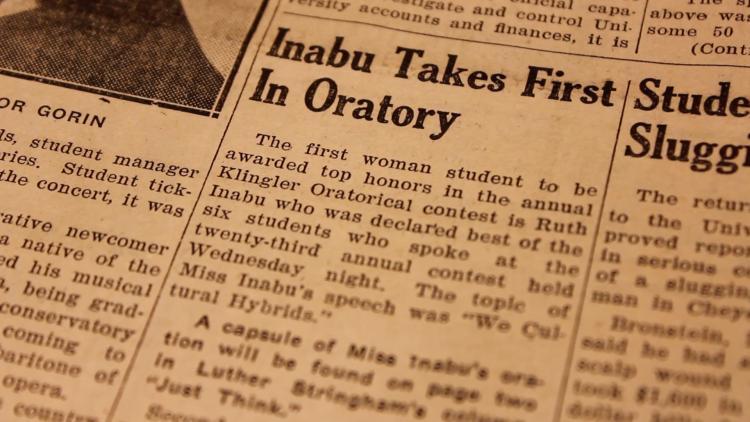

An archived yearbook page and newspaper clipping documenting the accomplishments of Ruth Chiyeko Inabu, who graduated in 1940. (Photo credits: Kelly Brichta/CU Boulder)

Archivist David Hays and three student interns are joining Lisbon and Friedel on the project. The team has already started expanding their collections with primary documents such as yearbooks, letters, diaries and home movies.

The archivists will do much of their work with support from a CU Boulder Outreach Award, but they also need some outside help. The group is reaching out to former students, staff and faculty to collect oral histories and other materials that document the experiences of Japanese and Japanese American community members at CU Boulder. Beyond filling in chronological gaps, the group hopes to explore a more human perspective.

“What we’re really interested in knowing is what was the actual personal experience of the students?” said Friedel. “What was it like being on campus?”

Friedel knows the success of the project will lean heavily on those who were there. As head of the archives, she’s always grateful to people who are willing to donate their own materials. She also emphasized the value of smaller contributions such as local knowledge.

She recently hosted a community preview event in the archives. The preview included a photo of the 1940 CU baseball team, which identified one player as George Masunaga, who graduated in 1941. Masunaga passed away in 2011, but several people at the event knew his family. They immediately offered to connect Friedel with his daughter for the project.

“We’re relying on our community members who may not have gone to CU, but they might know the families of people who did,” said Friedel. “Our community, in that sense, is not only alumni and former faculty and staff but the Japanese American community at large.”

The project will conclude at the end of June 2020. At that time, Lisbon and Friedel expect to have nearly 500 digitized items available online and a more complete historical record in the hallways under Norlin Library. They also have a bigger picture in mind.

“Most people never step foot in an archive because they’re intimidated by what it might be. It’s a symbol of the ivory tower of academia,” said Friedel. “As a result, the stories that have traditionally gotten documented in archives are about the majority.”

Friedel plans to use this as a pilot project. In the years to come, she expects to turn her focus to better documenting other underrepresented communities throughout the university’s history.

“To see a heritage reflected in an actual university’s history is a really big deal to someone who feels like they may not fit in,” said Friedel.