Think Saturn’s rings are old? Not so fast

This story was published by the European Planetary Science Congress and The Division for Planetary Sciences (EPSC-DPS). Read the original story here.

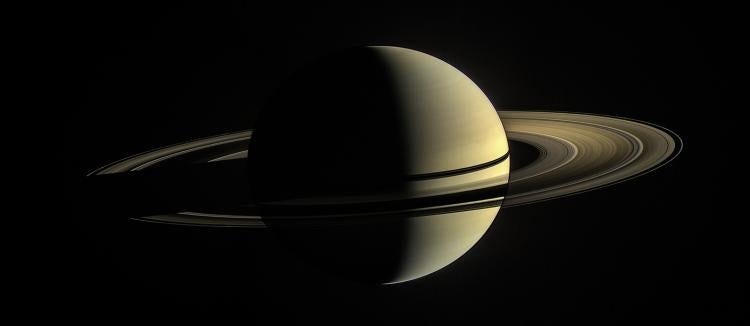

A team of researchers has reignited the debate about the age of Saturn’s rings with a study that dates the rings as most likely to have formed early in the solar system.

In a paper published today in Nature Astronomy and presented at the EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2019 in Geneva, the authors suggest that processes that preferentially eject dusty and organic material out of Saturn’s rings could make the rings look much younger than they actually are.

The findings have implications that go well beyond Saturn, said coauthor Hsiang-Wen (Sean) Hsu, a research associate at CU Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP).

“The rings around Saturn and other giant planets are witnesses of our solar system history,” Hsu said. “Determining how and when they formed, whether it was 4.5 billion or 200 million years ago, allows us to look back in time to understand the evolution of the solar system, and other planetary systems around other stars."

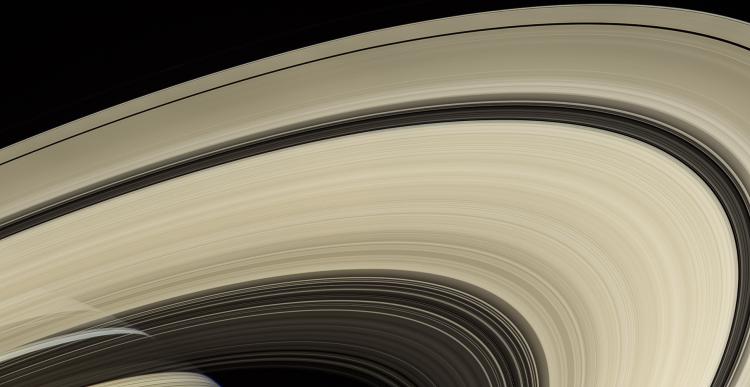

Cassini’s dive through the rings during the mission’s Grand Finale in 2017 provided data that was interpreted as evidence that Saturn’s rings formed just a few tens of millions of years ago, around the time that dinosaurs walked the Earth. Gravity measurements taken during the dive gave a more accurate estimate of the mass of the rings, which are made up of more than 95 percent water ice and less than 5 percent rocks, organic materials and metals. The mass estimate was then used to work out how long the pristine ice of the rings would need to be exposed to dust and micrometeorites to reach the level of other “pollutants” that we see today.

For many, this resolved the mystery of the age of the rings. However, Aurelien Crida, lead author of the new study, believes that the debate is not yet settled.

“We can’t directly measure the age of Saturn’s rings like the rings on a tree stump, so we have to deduce their age from other properties like mass and chemical composition. Recent studies have made assumptions that the dust flow is constant, the mass of the rings is constant, and that the rings retain all the pollution material that they receive. However, there is still a lot of uncertainty about all these points and, when taken with other results from the Cassini mission, we believe that there is a strong case that the rings are much, much older,” said Crida, of the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, CNRS.

Conveyer belt

Crida and colleagues argue that the mass measured during the Cassini mission finale is in extraordinarily good agreement with models of the dynamical evolution of massive rings dating back to the primordial Solar System.

The rings are made of particles and blocks ranging in size from meters down to micrometers. Viscous interactions between the blocks cause the rings to spread out and carry material away like a conveyor belt. This leads to mass loss from the innermost edge, where particles fall into the planet, and from the outer edge, where material crosses the outer boundary into a region where moonlets and satellites start to form.

More massive rings spread more rapidly and lose mass faster. The models show that whatever the initial mass of the rings, there is a tendency for the rings to converge on a mass measured by Cassini after around 4 billion years, matching the timescale of the formation of the Solar System.

“From our present understanding of the viscosity of the rings, the mass measured during the Cassini Grand Finale would be the natural product of several billion years of evolution, which is appealing. Admittedly, nothing forbids the rings from having been formed very recently with this precise mass and having barely evolved since. However, that would be quite a coincidence,” Crida said.

The Cassini-Huygens mission was a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). This 13-year-long exploration ended in September 2017 when the spacecraft intentionally dove into Saturn, burning up in the atmosphere.

“Despite the end of the mission, more Cassini results as well as inspired modeling and laboratory work will continue to shed light on Saturn, the real Lord of the Rings, in the years to come,” Hsu said