Neanderthals used resin 'glue' to craft their stone tools

Archaeologists working in two Italian caves have discovered some of the earliest known examples of ancient humans using an adhesive on their stone tools—an important technological advance called “hafting.”

The new study, which included CU Boulder's Paola Villa, shows that Neanderthals living in Europe from about 55,000 to 40,000 years ago traveled away from their caves to collect resin from pine trees. They then used that sticky substance to glue stone tools to handles made out of wood or bone.

The findings add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that these cousins of Homo sapiens were more clever than some have made them out to be.

“We continue to find evidence that the Neanderthals were not inferior primitives, but were quite capable of doing things that have traditionally only been attributed to modern humans,” said Villa, corresponding author of the new study and an adjoint curator at the CU Museum of Natural History.

That insight, she added, came from a chance discovery from Grotta del Fossellone and Grotta di Sant’Agostino, a pair of caves near the beaches of what is now Italy’s west coast.

Those caves were home to Neanderthals who lived in Europe during the Middle Paleolithic period, thousands of years before Homo sapiens set foot on the continent. Archaeologists have uncovered more than 1,000 stone tools from the two sites, including pieces of flint that measured not much more than an inch or two from end to end.

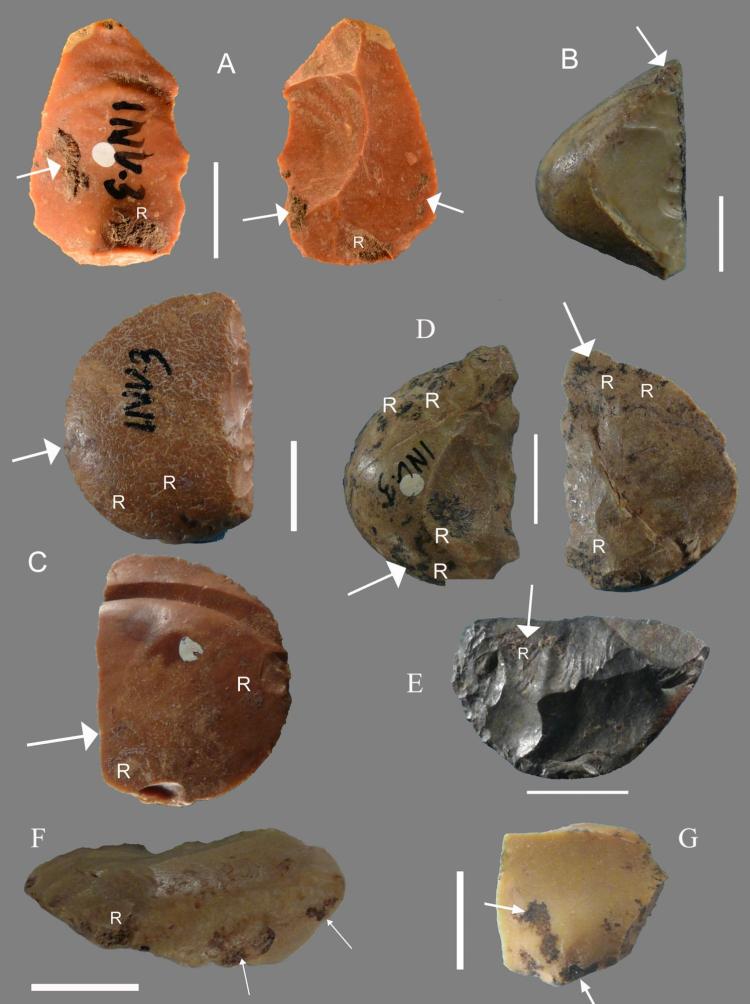

In a recent study of the materials, Villa and her colleagues noticed a strange residue on just a handful of the flints—bits of what appeared to be organic material.

“Sometimes that material is just inorganic sediment, and sometimes it’s the traces of the adhesive used to keep the tool in its socket,” Villa said.

Warm fires

To find out, study lead author Ilaria Degano at the University of Pisa conducted a chemical analysis of 10 flints using a technique called gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. The tests showed that the stone tools had been coated with resin from local pine trees. In one case, that resin had also been mixed with beeswax.

The findings, Villa said, indicate that Italian Neanderthals didn’t just resort to their bare hands to use stone tools. In at least some cases, they also attached those tools to handles to give them better purchase as they sharpened wooden spears or performed other tasks like butchering or scraping leather.

“You need stone tools to cut branches off of trees and make them into a point,” Villa said.

The find isn’t the oldest known example of hafting by Neanderthals in Europe—two flakes discovered in the Campitello Quarry in central Italy predate it. But it does suggest that this technique was more common than previously believed.

The existence of hafting also provides more evidence that Neanderthals, like their smaller human relatives, were able to build a fire whenever they wanted one, Villa said—something that scientists have long debated. She explained that pine resin dries when exposed to air. As a result, Neanderthals needed to warm it over a small fire to make an effective glue.

“This is one of several proofs that strongly indicate that Neanderthals were capable of making fire whenever they needed it,” Villa said.

In other words, enjoying the glow of a warm campfire isn’t just for Homo sapiens.

Other coauthors on the study included researchers at Paris Nanterre University in France, University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, University of Wollongong in Australia, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, Istituto Italiano di Paleontologia Umana and the University of Pisa.

The research was funded by a National Science Foundation grant to Paola Villa and Sylvain Soriano.