Students in Focus: When deep space calls, students answer

In one of the spacecraft operations centers inside CU Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP), a woman’s calm voice pipes in over a speaker:

“Loss of signal, MMS-4,” the voice reports.

The room looks like a smaller version of the NASA flight control centers that show up in every space movie. The announcement is a routine cue that one of the four spacecraft that make up the Magnetospheric MultiScale (MMS) mission has finished its latest round of transmitting data back to Earth.

Often the first person to hear such alerts isn’t a grizzled mission control veteran, but rather a CU Boulder student. That’s because LASP employs student “command controllers” to help operate the space missions under its supervision.

The job comes with long hours and late nights, said Reidar Larsen, a graduate student who started working at LASP as an undergraduate at CU Boulder. But it also gives students something they can’t get at any other university: hands-on experience with scientific instruments orbiting hundreds of miles from Earth.

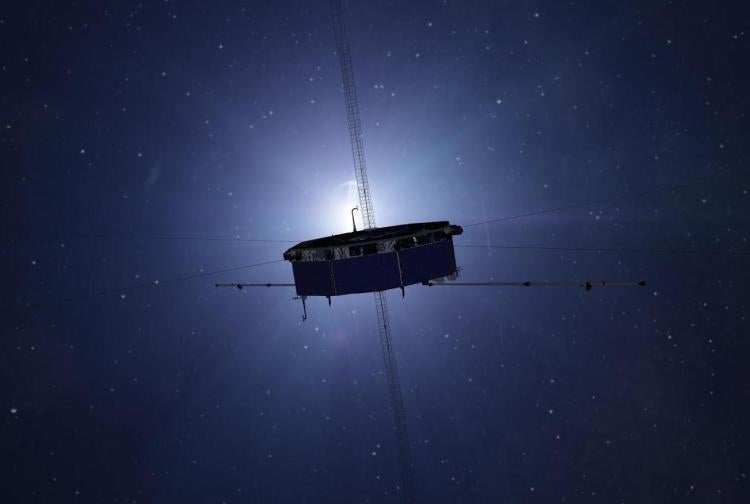

From top to bottom: Students and professionals work together in the operations center for the Magnetospheric MultiScale (MMS) mission; an artist's depiction of one of the four spacecraft that make up MMS; alien figurines decorate a row of computer consoles in the Kepler mission operations center. (Credits: Casey A. Cass/CU Boulder; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center; LASP)

“LASP is the only place in the world that has students work on spacecraft like this,” he said. “It’s completely unique.”

The students have a soundboard of audio alerts that would rival most morning radio shows. There’s a clip of Chewbacca roaring, R2D2 beeping and the one you don’t want to hear: “Red alert. Red alert. Houston, we have a problem.” Each one means something different for different spacecraft.

“If something big happens, we have audible alarms that say ‘Hey, look at me. Something’s wrong,’” said Larsen.

Not your typical all-nighter

Learning the ropes, however, is a bit of a juggling act. In addition to MMS, LASP oversees aspects of the operations for NASA’s Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE) and Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere (AIM) missions. The institute has also branched into operating toaster-sized satellites called CubeSats.

On any given day, roughly one dozen student operators might send new instructions to one of those spacecraft, run diagnostics to make sure it’s working correctly or troubleshoot if something has gone wrong.

“We rely a lot on our students to do analyses, to help command the spacecraft,” said Lee Reedy, a professional flight director at LASP. “We’re teaching them a lot of valuable skills here, and they’ve gone on to do all sorts of great things.”

That much responsibility takes a lot of commitment. To qualify as command controllers at LASP, students undergo an entire summer of training, amounting to 500 hours. And because spacecraft don’t stick to regular work hours, the students often pull shifts on weekends and nights after their peers have gone to sleep.

“We all get along really well,” he said. “Most of the people you work with are also in your classes, so not only can you talk with them about work, but you can also commiserate about your homework assignments.”

Ginger Beerman, a senior studying aerospace engineering at CU Boulder, agrees. “We learn a lot of things that you wouldn’t learn in your classes,” she said.

Fixing problems

In the operations center, however, things don’t always go according to plan.

Larsen remembers a difficult week in 2016 when the Kepler Space Telescope, a NASA mission that LASP formerly operated, went into emergency mode with little warning. Kepler was floating almost dead in the water, a potentially catastrophic systems failure that engineers eventually chalked up to a “fault storm.”

Students and professionals alike at LASP worked around the clock until they could pull Kepler out of the emergency. That sort of problem solving is what Larsen loves most about being a command controller.

“You get a dataset and have to learn how you can pull it apart and make sure the spacecraft is working right,” Larsen said. “If there is something that’s odd, you try to diagnose that and figure out what’s really going on.”

Such an approach to fixing problems also explains why former LASP command controllers have gone on to work at hubs for the aerospace industry. That includes Lockheed Martin Space, Blue Origin and various NASA centers.

At LASP, “the professionals value your opinion,” said Katie Steward, a junior studying aerospace engineering. “They really take your input and make decisions based off of it.”

Fellow junior Trevor Weschler added that his time at LASP has given him something even better than a resume boost: a personal connection to space.

“That’s been really cool—to spend my Friday talking to something in deep space,” he said. “There aren’t many people who can say that.”