Noise pollution causes chronic stress in birds, hindering reproduction

Western bluebirds nesting near noisy oil and gas operations have smaller chicks and lay fewer eggs that hatch. Credit: Dave Keeling

Birds exposed to constant noise from oil and gas operations show physiological signs of chronic stress and—in some cases—have chicks whose growth is stunted, according to new CU Boulder research.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), also found that western bluebirds—which tend to gravitate toward noisy environments—lay fewer eggs that hatch when they nest there.

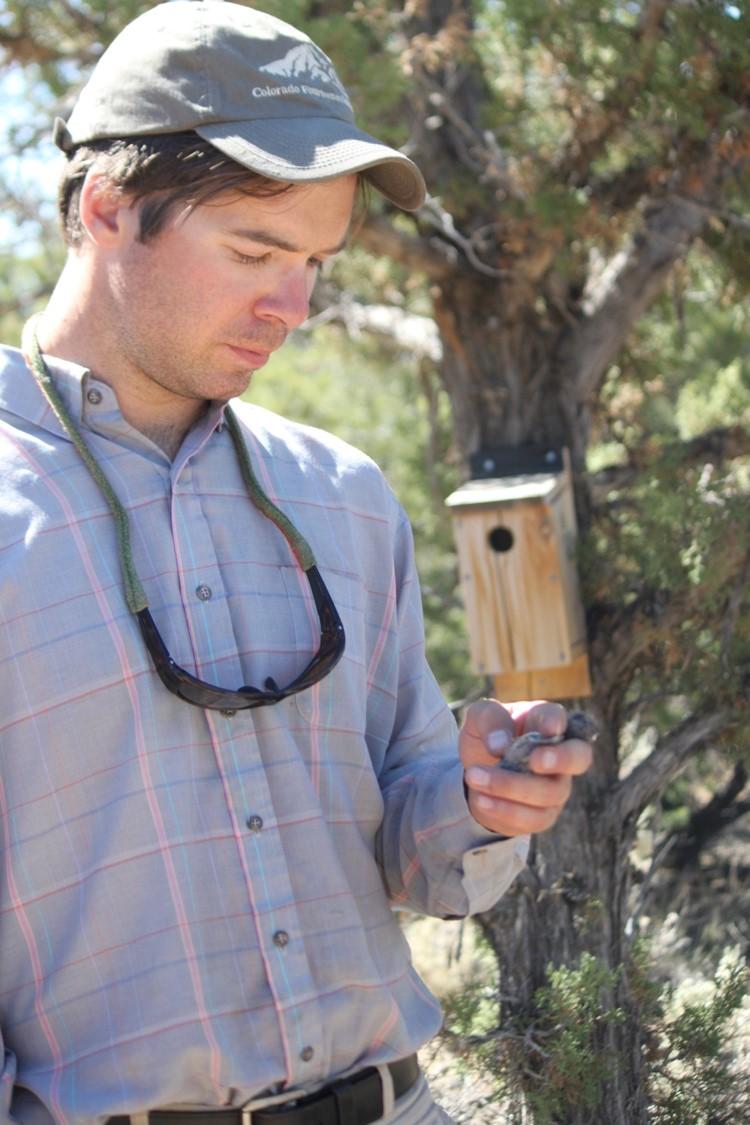

Nathan Kleist checks a bird box near an oil and gas operation in New Mexico. Credit: Nathan Kleist

“In what we consider to be the most integrated study of the effects of noise pollution on birds to date, we found that it can significantly impact both their stress hormones and their fitness,” said lead author Nathan Kleist, who conducted the research while at CU Boulder and graduated with a PhD in evolutionary biology in May. “Surprisingly, we also found that the species we assumed to be most tolerant to noise had the most negative effects.”

The authors, which include researchers from California Polytechnic State University and the Florida Museum of Natural History, say the findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting noise pollution from human activity is harmful to wildlife.

They also shed light on how stress from chronic noise exposure may impact humans.

For the study, the researchers followed three species of cavity nesting birds, including western and mountain bluebirds and ash-throated flycatchers, which breed near oil and gas operations on Bureau of Land Management property in New Mexico. Kleist and his team erected 240 nest boxes on 12 pairs of sites.

For three breeding seasons, the team took blood samples from adult females and their offspring and assessed hatching success, nestling body size and feather length.

Across all species and life stages, the birds nesting in areas with more noise had lower baseline levels of a key stress hormone called corticosterone.

“You might assume this means they are not stressed. But what we are learning from both human and rodent research is that, with inescapable stressors, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in humans, stress hormones are often chronically low,” said co-author Christopher Lowry, a stress physiologist in the department of integrative physiology at CU Boulder.

He notes that when the fight-or-flight response is constantly revved, the body sometimes adapts to save energy and can become sensitized. Such “hypocorticism,” has been linked to inflammation and reduced weight gain in rodents.

In the current study, Kleist also found that nestlings in noisy areas had a hair-trigger response to the acute stress of being held for 10 minutes, producing more stress hormones than those bred in quiet nests and taking longer to return to baseline levels.

“Whether stress hormone levels are high or low, any kind of dysregulation can be bad for a species,” said senior author Clinton Francis, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Cal Poly. “In this study, we were able to demonstrate that dysregulation due to noise has reproductive consequences.”

Nestlings in the noisiest areas had smaller feathers and bodies. Credit: Nathan Kleist

Chicks in both the quietest and loudest areas had reduced feather growth and body size, leaving a sweet spot in areas of moderate noise where nestlings seemed to grow fastest. The researchers hypothesize this occurs because adults in the quietest areas are exposed to more predators, leaving less time to forage for young because they are more cautious going to and from the nest. Meanwhile, in the loudest areas, the machinery noise masks calls from other birds—a signal of whether predators are present—chronically stressing moms and nestlings.

“If you were trying to talk to your friends and your children and you were always at a loud party, you would get worn out,” said Kleist, who likens the sound of an oil and gas compressor to the drone of a highway.

Previous research has shown that some bird species opt to leave noisy areas. But the new study shows what happens to those that remain.

For the western bluebird, previously suspected to be resilient to noise, the reduced hatching rates are concerning, said Francis.

“This is an example of an ‘ecological trap’: when an organism develops a preference for something that is actually bad for them.”

None of the species studied are endangered. But the researchers suspect if other species experience similar effects in noisy areas, avian populations could decline as human-caused noise increases.

One recent study found that anthropogenic noise already doubled background-sound levels in 63 percent of protected areas tested.

“There is starting to be more evidence that noise pollution should be included, in addition to all the other drivers of habitat degradation, when crafting plans to protect areas for wildlife,” said Kleist, now a visiting professor at State University of New York. “Our study adds weight to that argument.”

[video:https://youtu.be/6JbbyguBGEM]