Chaco Canyon petroglyph may represent ancient total eclipse

As the hullabaloo surrounding the Aug. 21 total eclipse of the sun swells by the day, a CU Boulder faculty member says a petroglyph in New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon may represent a total eclipse that occurred there a thousand years ago.

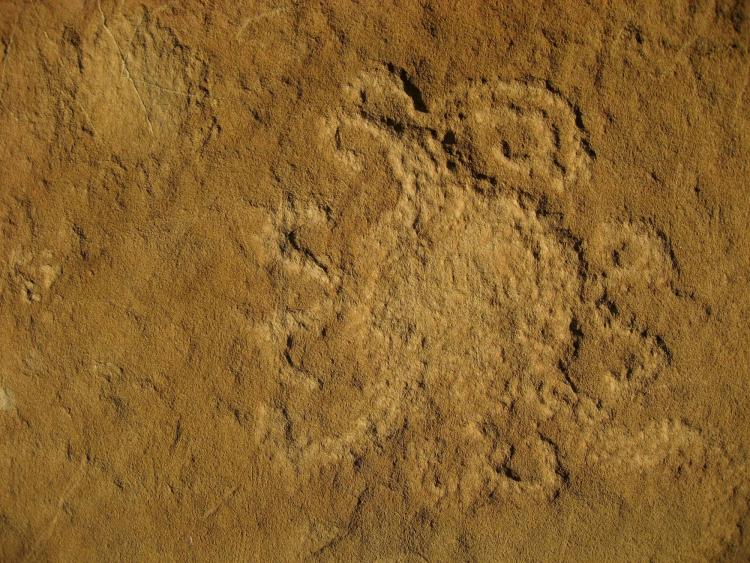

CU Boulder Professor Emeritus J. McKim “Kim” Malville said the petroglyph—carved in a rock by early Pueblo people—is a circle that resembles the sun’s outer atmosphere known as its corona, with tangled protrusions looping off the edges. Discovered in 1992 during a Chaco Canyon field school for CU Boulder and Fort Lewis College students led by Malville and then-Fort Lewis Professor James Judge, the object may illustrate the total eclipse of the sun that occurred over the region on July 11, 1097.

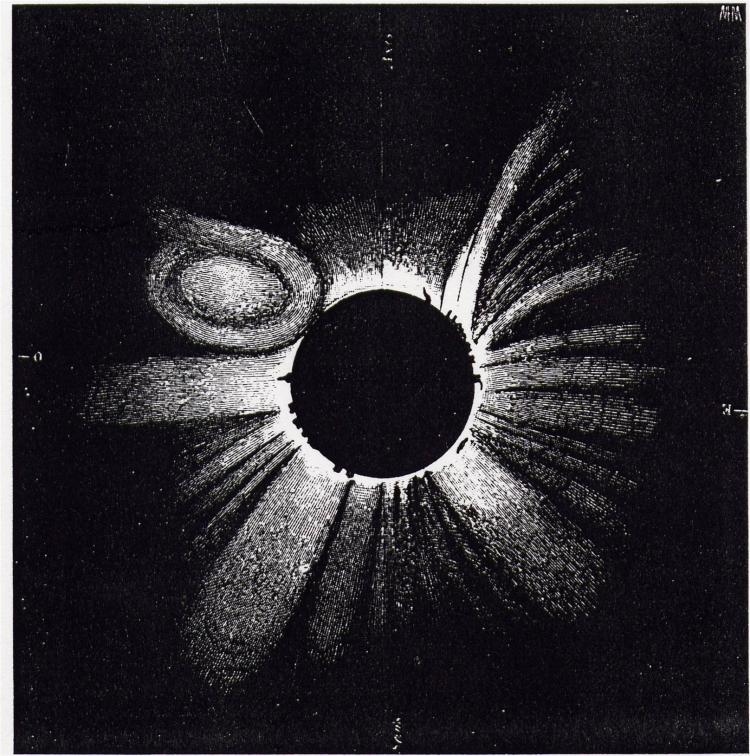

“To me it looks like a circular feature with curved tangles and structures,” said Malville of CU Boulder’s astrophysical and planetary sciences department. “If one looks at a drawing by a German astronomer of the 1860 total solar eclipse during high solar activity, rays and loops similar to those depicted in the Chaco petroglyph are visible.”

One tangled loop jutting from the petroglyph circle may illustrate a coronal mass ejection (CME), an eruption that can blow billions of tons of plasma from the sun at several million miles per hour during active solar maximum periods. But if the sun was in a “quiet phase” of its roughly 11-year cycle, one would expect few if any CMEs, and the likelihood of one occurring during a solar eclipse would be negligible, Malville said.

“This was a testable hypothesis,” Malville said. “It turns out the sun was in a period of very high solar activity at that time, consistent with an active corona and CMEs.”

Malville and Professor José Vaquero of the University of Extremadura in Cáceres, Spain, published a paper on the petroglyph in the Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry in 2014. Chaco Canyon, the zenith of Pueblo culture in the Southwest a thousand years ago, is believed by archeologists to have been populated by several thousand people and held political sway over an area twice the size of Ohio.

The two used several sources to assess the activity of the sun around the time of the 1097 eclipse. That included data from ancient tree rings, formed annually and which have been cross-dated to create time series going back thousands of years and which also contain traces of the isotope carbon-14. Created by cosmic rays hitting Earth’s atmosphere, carbon-14 amounts in the tree rings can be correlated with sunspots—the less carbon-14, the more sunspots, which indicates higher solar activity, Malville said.

Kim Malville at a “pecked basin” in Chaco Canyon, similar to the one east of Piedra del Sol, where inhabitants often left ceremonial offerings.

They also used records of naked-eye observations of sunspots, which go back several thousand years in China. A third method involved looking at historical data compiled by northern Europeans on the annual number of so-called “auroral nights,” when the northern lights were visible, an indication of intense solar activity.

The free-standing rock hosting the possible eclipse petroglyph, known as Piedra del Sol, also has a large spiral petroglyph on its east side that marks sunrise 15 to 17 days before the June solstice, Malville said. A triangular shadow cast by a large rock on the horizon crosses the center of the spiral at that time. Such a phenomenon may have been used to start a countdown to the summer solstice and related festivities, he said.

In addition to the spiral petroglyph, the east side of Piedra del Sol contains a bowl-shaped depression where Chacoans likely left offerings like cornmeal. The southwest side of the rock faces a small butte on the horizon that marks the December solstice event, and the rock also has carved steps, indicating it likely had some kind of a ceremonial importance, he said.

“This possible eclipse petroglyph on Piedra del Sol is the only one we know of in Chaco Canyon,” Malville said. “I think it is quite possible that the Chacoan people may have congregated around Piedra del Sol at certain times of the year and were watching the sun move away from the summer solstice when the eclipse occurred.”

Two other Chaco Canyon rock art pieces may be related to astronomical events, Malville said. One is thought by some to be a depiction of an A.D. 1054 supernova bright enough to be visible in the daytime for several weeks, while another resembles a comet, perhaps Halley’s Comet, which would have been visible from there in A.D. 1066.

“The appearance of the spectacular supernova and comet may have alerted the residents of the canyon to pay attention to powerful and meaningful events in the sky,” he said.