Pushing Boundaries: Caricatures satirized 18th-century bawdy women

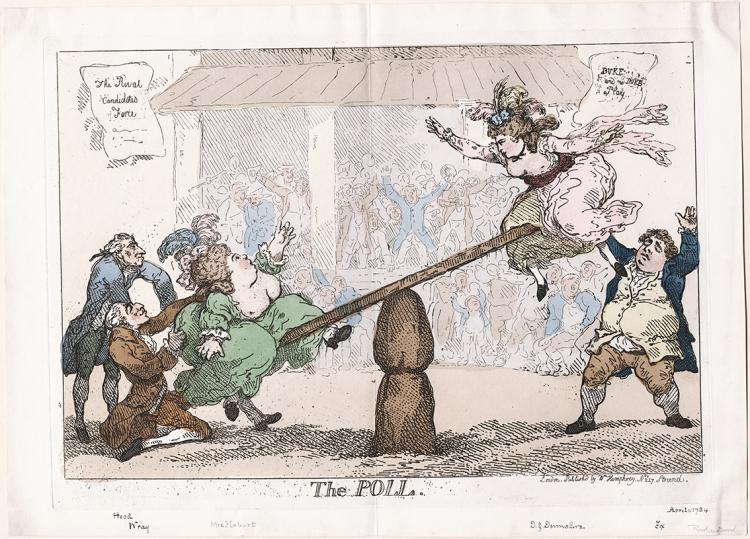

Thomas Rowlandson, British (1756–1827), The Poll, c. 1784, Impression I, etching with hand coloring, 11 ½ x 13 ¾ inches plate. Image courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

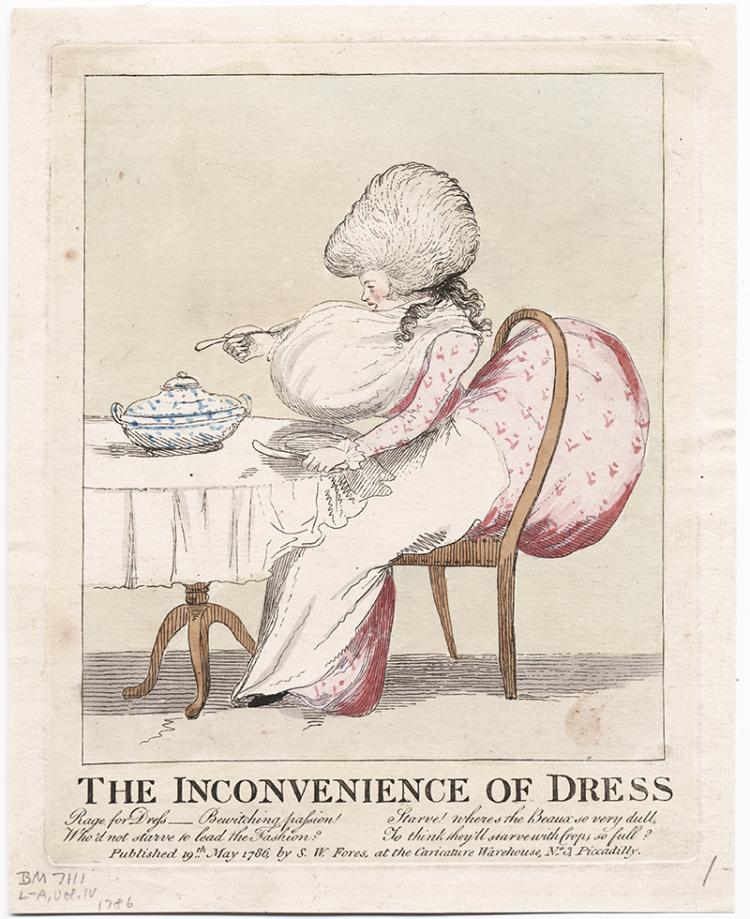

Anonymous, British, Inconvenience of Dress, 1786, etching and engraving with hand coloring, 10 ¼ x 8 inches sheet. Image courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Raucous physical humor and over-the-top visual comedy are featured at the CU Art Museum in an exhibit of British caricatures and satires made in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Bawdy humor was frequently used in images to poke fun at the political follies and social foibles of royals, politicians, entertainers, and men and women of fashion. This form of humor was especially cutting when used to critique the behavior of accomplished women, whose growing prominence and engagement in the public sphere elicited the criticism of commentators and drew the attention of graphic satirists.

Featuring a selection of prints from Yale University’s Lewis Walpole Library, the Bawdy Bodies: Satires of Unruly Women exhibit offers a view into the manners of an era over 200 years ago, revealing parallels between the 18th century and today.

The Bawdy Bodies exhibit will run from Feb. 2 through June 24 at the CU Art Museum. For more information, visit the CU Art Museum website.

Hope Saska, curator at the CU Art Museum, talks about what the exhibit reveals about that time.

Characterized by comically grotesque figures performing lewd and vulgar actions, what was going on in 18th-century Britain that led to such cartoons and satirical artwork?

There was relative freedom of the British press and a developing cult of celebrity and familiarity with political figures and stage celebrities. Then you have the Revolutionary War in America and the French Revolution, and these moments of upheaval spawn images of the great anxiety they had about political and social changes in contemporary life and culture. Humor allowed the people of the time to explore and examine an unnerving time.

Why were scandals, dalliances and affairs of the royals such rich fodder for the satirists?

Certainly, the upper elites of society understood that there were dalliances among royals however, the position of royalty was in question. For example, Wiliam Dent’s caricature about the Duke of Clarence’s affair with stage actress Dorothy Jordan critiques behavior unbecoming of a royal. The satire shows group of women examining a chamber pot and discussing the affair. In England, “jordan” was also a slang term for a chamber pot and this becomes a very rude joke. They’re saying, ‘Maybe the Duke needs a new Jordan.’

These prints circulated among wealthy people who lived in London. Some people wrote to caricaturists asking them to satirize certain individuals, including women, to defame their reputation. Occasionally male politicians requested to be included in caricatures, because if you were important enough to be put in a caricature then you must be a person with power. Unlike men, women had no recourse to their representation in satire.

Why were these graphic caricatures and satires especially critical of accomplished women?

I think they didn’t know quite what to do with women. On the one hand, there’s a conversation about what a moral education should be for a woman and there was a belief that women shouldn’t have the same education as men. Women in the exhibition are ridiculed for being interested in politics and also for being too interested in fashion. Women were becoming politically and socially more visible in a way they hadn’t been, so the caricatures reflect that anxiety.

What will people see in this exhibit?

A: A selection of prints from the Lewis Walpole Library at Yale University that represent the different ways women were depicted in caricatures and satires. We have sections dedicated to women of fashion, women who were interested in gambling (gambling was a popular pastime in the 18th century), women who were artists and intellectuals. We also have a fascinating collection of books from University Library’s Special Collections & Archives, including books written by women on female education. There is a slideshow to contextualize some of the characters. There’s a lot to take in!

What finally ended the era of this kind of satire? Was it when the pendulum swung to the Victorian sensibility?

By about 1815, the world of satirical prints had changed. Some satirists had passed on and the advent of the magazine fundamentally changed the world of publishing and circulation. There was a general social and cultural shift leading up to the Victorian era with the end of the Napoleonic era and the beginning of the reign of George IV. Times changed.

What are the parallels between the 18th century and today?

We are still concerned about understanding social roles and the line between celebrity and politics, and where those two categories overlap. Carrying over into today, you have leading fashion women we look at as role models. We have that same interest in knowing the latest gossip.

What message do you want people to take away from seeing this exhibit?

A lot of the themes and concepts are relevant to the way we see ourselves today. There’s an implicit direction to think about how we represent political and cultural figures today in the media. There’s a lot here that will resonate with our own cultural experience. It’s also a way to showcase artworks that aren’t always on museum walls. For a long time, caricatures were considered lowbrow. This is an avenue for people to learn about the 18th century and reflect upon parallels to today.