Researchers model a dangerous glacial lake in the Himalayas and propose solutions

INSTAAR senior research associate Alton Byers has organized frequent research expeditions to the Himalayas for more than 50 years. Last summer, he returned to the remote Kanchenjunga region in Nepal, an area he has visited three times since 2019. His team was there to gather more data for an ongoing study of glacial, ecological and socioeconomic changes in the region. But, his attention was soon diverted when a friend, a young man from the local Tibetan community, brought an emerging issue to his attention.

The man told Byers that locals had noticed large meltwater ponds forming at the toe of the Kanchenjunga Glacier, upstream from the villages of Ghunsa and Kambachen. He worried that the ponds could trigger a flood — a scenario that has played out in nearby areas more than once.

“He asked if we could go take a look at it,” Byers said. “We were on our way up to the Kanchenjunga base camp, so we made a detour. Sure enough, you could see these considerable lakes, perhaps a half-a-square-mile and growing.”

Byers sprung into action. First, he interviewed other community members about the ponds — they confirmed the observations and growing concern. Then, over the ensuing months, he assembled a team of experts to conduct a study of how the ponds were changing. The study was published in Water earlier this month.

The new paper outlines a number of potentially dangerous flood scenarios that could be triggered at the site in the future. In order to protect local communities, the researchers urge regional authorities to implement mitigation measures, including a monitoring program and an early warning system for flooding.

Modeling disaster

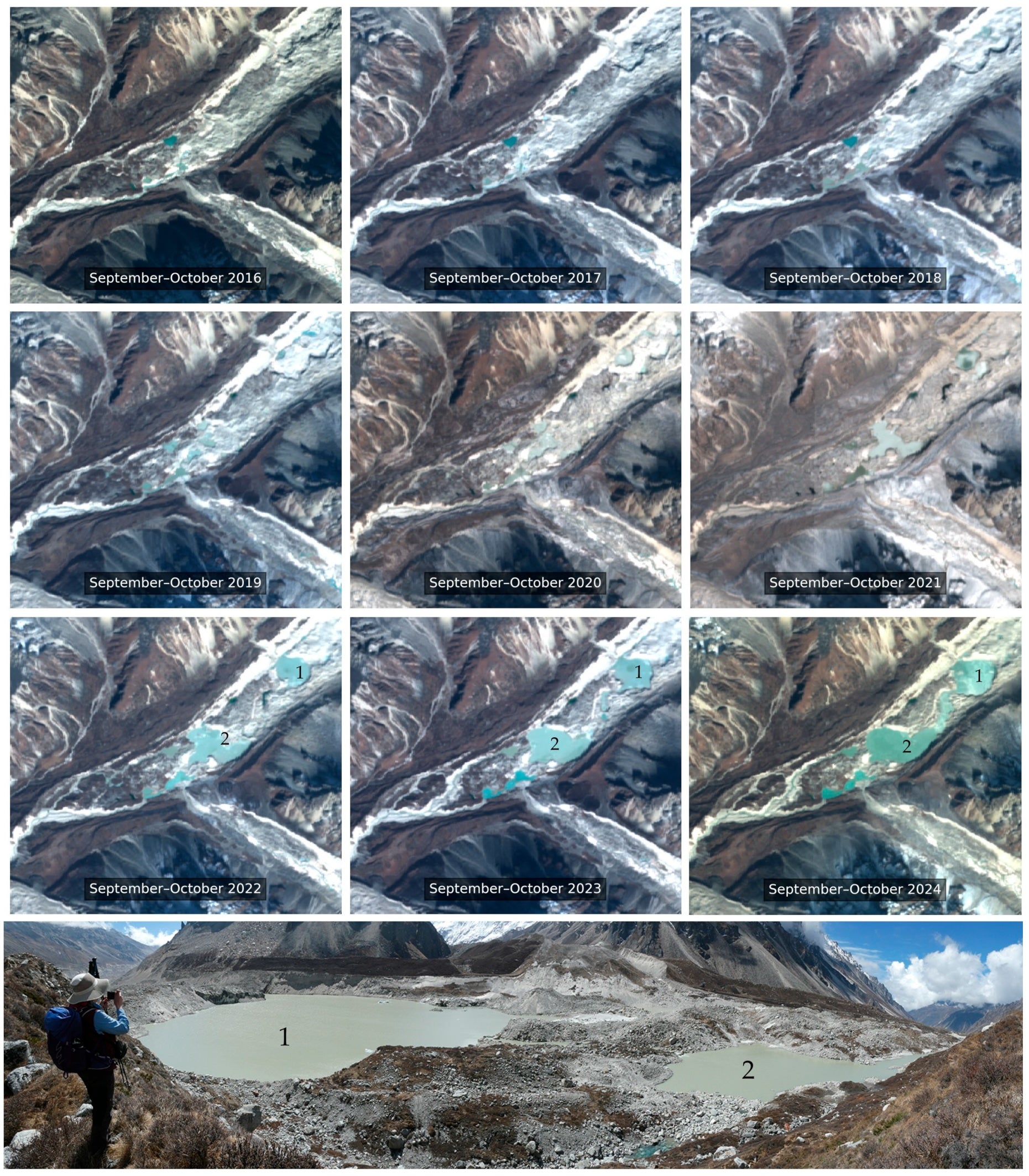

Byers’ first call for collaboration was to Sonam Wangchuk, an expert in snow and ice research via satellite imagery at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development. Wangchuck, now onboard, gathered satellite images of the site. The images were striking. From 2022 to 2024, the ponds grew from puddles to large, interconnected bodies of water.

“It’s sort of an indicator of how these melting processes are accelerating,” Byers said.

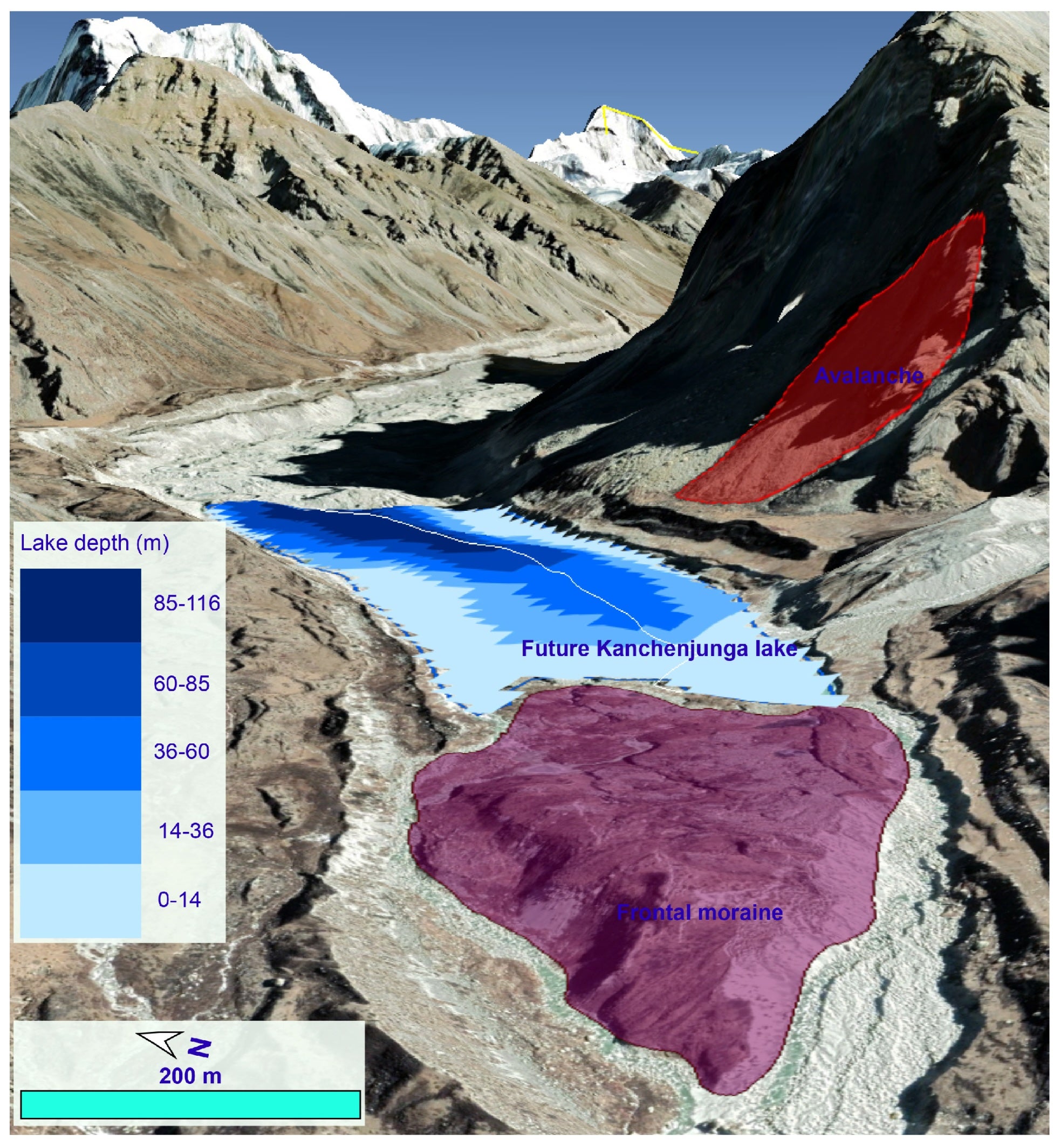

Next, Byers and collaborators levied statistical methods to look to the future. They estimated that the meltwater ponds could form a large glacial lake. That lake, if it forms, will be vulnerable to outburst flooding, which could be triggered by melting processes, structural collapse or rockfall from surrounding slopes.

Finally, the researchers focused their efforts on modeling potential floods. They identified four scenarios, from small to large.

Under the mildest scenario, the flood surge would travel 75 miles down the Tamor River, flooding 16 existing buildings and 30 bridges along the way. Under the worst-case scenario the flood would travel at least 175 miles and impact 90 buildings and 44 bridges. According to the authors, the flooding would also likely impact livestock, crops and tourism infrastructure.

Mitigating disaster

Byers warns that, without adequate preparation, glacial outburst flooding can be deadly. In 1941, a glacial lake in Peru collapsed and sent a surge of water into the downstream city of Huaraz killing thousands.

In light of events like this, some regional governments around the world have developed early warning systems for potential outburst floods. Others have also implemented novel mitigation measures. In Peru, government engineers drained water from a number of dangerous glacial lakes in efforts spanning decades.

Byers and his coauthors advise local and regional authorities in the Kanchenjunga region to take similar measures to prevent a flood originating from the study site. Their recommendations include establishing early warning systems for flooding, partnering with research organizations in Kathmandu to monitor the site and adapting zoning laws to prevent new buildings in flood zones.

According to Byers, one of the cheapest and most effective early warning systems is deceptively simple: cell phones.

“Not everyone can afford multi-million dollar early warning systems that rely on laser readings of water depth,” he said. “But, studies have shown that cell phones, at least during the daytime, are one of the better early warning systems out there.”

In the end, Byers hopes the study can help the same people that brought the issue to his attention.

“The goal was always to share the research with the local community,” he said. “Then they have all of the information they need to make the best decisions possible.”

If you have questions about this story, or would like to reach out to INSTAAR for further comment, you can contact Senior Communications Specialist Gabe Allen at gabriel.allen@colorado.edu.