Black-Figure Vase Painting

The black-figure technique of vase painting was invented in the city of Corinth around 700 B.C.E. It was around this time that Corinthian vase painters began adorning their vessels with animal friezes and occasional mythological scenes and they developed this new style of painting to depict these motifs. In this style of decoration, figures were drawn in silhouette on the surfaces of leather-hard vessels using black slip. Details were added using incision, which revealed the color of the clay beneath. Although it was invented by the Corinthians, the Athenians quickly adopted the black-figure technique and made it their own. Easily one of the most remarkable examples of the black-figure technique of vase painting is an amphora by Exekias showing the Greek heroes Achilles and Ajax playing a game of dice. This scene was so famous in antiquity that it was copied over 150 times.

As the name indicates, the figures on these vases were black silhouettes set against the color of the clay beneath, which, in Athens, was a red-orange color. The production of black-figure vases was a lengthy process and it began with the procurement of the clay. Potters in ancient Athens used a process called levigation, whereby clay is mixed with water and heavy impurities allowed to sink to the bottom. This process was repeated until the clay had reached a sufficient level of purity and therefore plasticity. The clay was wedged in order to eliminate air bubbles before it was thrown on the potter's wheel. In ancient Greece, the potter's wheel was a large wooden or stone disk attached to an axle, which sat atop a pivot point on the ground. The wheel was kept in motion by a slave or potter's assistant, allowing the potter to use both hands to form the vessels (1). Most pottery was made in sections and appendages like lids, spouts, and handles added after the vessel had dried to a leather-hard state.

Once a vessel had dried to a leather-hard state, it could be burnished and/or decorated. The process of burnishing a pot involves rubbing it vigorously with a hard, smooth object, such as leather, wood, or a stone, in order to compact and smooth the surface of the clay (2). A light coating of red ochre was sometimes applied and the vessel re-burnished, enhancing the natural red-orange color of the clay (3). A sketch of the final design was then made on the surface of the vessel using charcoal. The vase painter then applied black slip to the areas to be decorated and used a sharp tool to incise any necessary details, a process that revealed the color of the clay beneath.

After the decoration was applied, the vase painter -- who may sometimes have also been the potter -- could choose to add additional colors. Whites, reds, and yellows were the only colors able to withstand the high heat of the pottery kilns. Colors were applied according to certain conventions that developed along with the black-figure technique. White, for example, was used to indiciate women's flesh, while men's flesh was usually left in the black color of the slip, although it was sometimes painted over in red. The application of red and white could be used to create patterns, such as stripes on drapery or the ribs on an animal (4). White could be used to enhance the beards of elderly men, while red sometimes picked out the hair of other human figures or the manes of horses (5).

Once the vessel has been decorated, it progresses through a three-stage firing process. This three-step firing process, which consisted of a cycle of oxidizing, reducing, and re-oxidizing the atmosphere inside the pottery kiln, was necessary to achieve the lustrous black gloss and the reserved red-orange decorative panels (6). The three-stage process occurred in the following order:

- Oxidizing: the kiln was heated to 800 degrees Celsius. Air admitted through vents allowed oxygen to enter the firing chamber and, at this stage, any slip on the surface of the vase turned a brownish-red color while the reserved clay areas fired to a light red color.

- Reducing: any vents were closed to reduce the level of oxygen in the kiln and the temperature was increased to 950 degrees Celsius. In addition to these changes, wet sawdust or green wood was added, causing incomplete combustion. The combination of robbing the oxygen from the red clay and releasing carbon monoxide, rather than carbon dioxide, allowed the reserved areas of the vessel's surface to turn from light red to a matte dark gray while the the slip-covered areas of the surface sintered -- a process in which the quartz particles in the slip fused together, enclosing the clay beneath -- to a deep shiny metallic black (7).

- Oxidizing: oxygen was re-admitted to the kiln and the temperature was reduced to 900 degrees Celsius. The reserved areas of the vessel absorbed the oxygen and reverted back to their red-orange color while the slip-covered areas remained black because the sintered surface could no longer absorb oxygen. It is important to note that if the temperature inside the kiln exceeded 1050 degrees Celsius during this third phase, the entire pot would re-oxidize and any black color would be lost (8).

Ancient Greek potters and vase painters did not have thorough understandings of the chemistry involved in these processes, nor tools with which to measure temperature precisely. Pottery production was, then, a process of trial and error and, as consumers of their art, we can marvel at their abilities to make pieces that were both beautiful and functional.

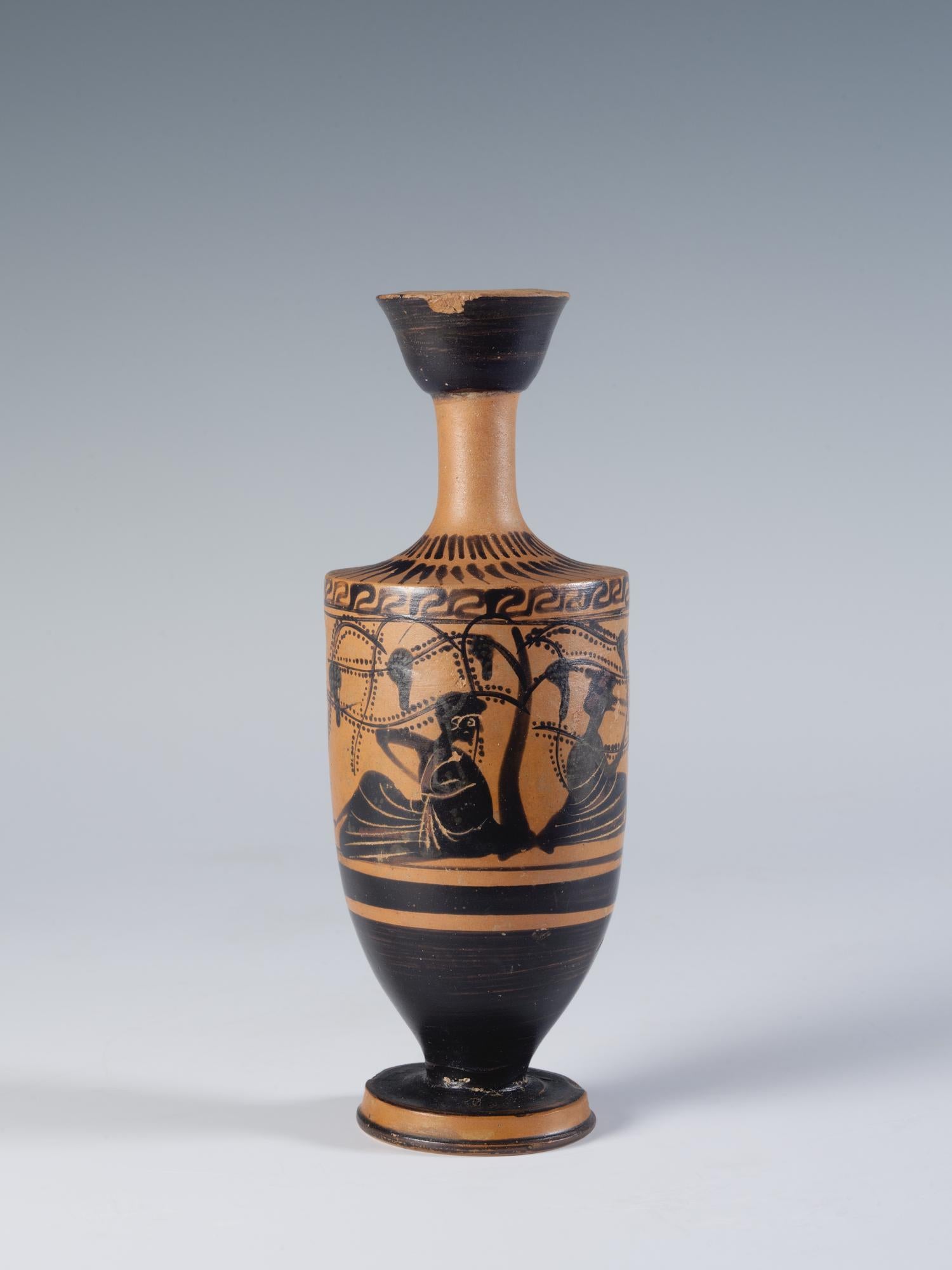

The CU Art Museum's collection contains one example of Attic black-figure decoration, a 5th century B.C.E. lekythos showing two human figures reclining beneath a productive grape arbor.

Footnotes

- Douglas R. Allen, "An Overview of Greek Vases," Utah Museum of Fine Arts (https://umfa.utah.edu/sites/default/files/2017-10/Greek-and-Roman-Art.pdf), accessed 06 February 2019.

- Andrew J. Clark, Maya Elston, and Mary Louise Hart, Understanding Greek Vases: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002): 74.

- Clark , Elston, and Hart, Understanding Greek Vases: 118.

- John Boardman, Athenian Black Figure Vases: The Archaic Period (London: Thames and Hudson, 1975): 198.

- Gisela M. A. Richter, A Handbook of Greek Art (London: Phaidon, 2006).

- Clark , Elston, and Hart, Understanding Greek Vases: 91.

- Clark , Elston, and Hart, Understanding Greek Vases: 92.

- Andrew Wilson, "The Chemistry of Athenian Pottery," The Classics Pages (http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~loxias/chemistry.htm), accessed 31 January 2019.