Recruiting and Unleashing Youthful Talent:

The Best Imaginable Way to Observe the One-Year Anniversary of the “Not my First Rodeo”

| There was once a small little frog, And one day he hopped on a log. Then out jumped a bug Who gave him a hug, And together they fell in the bog. | There once was a small piece of bread |

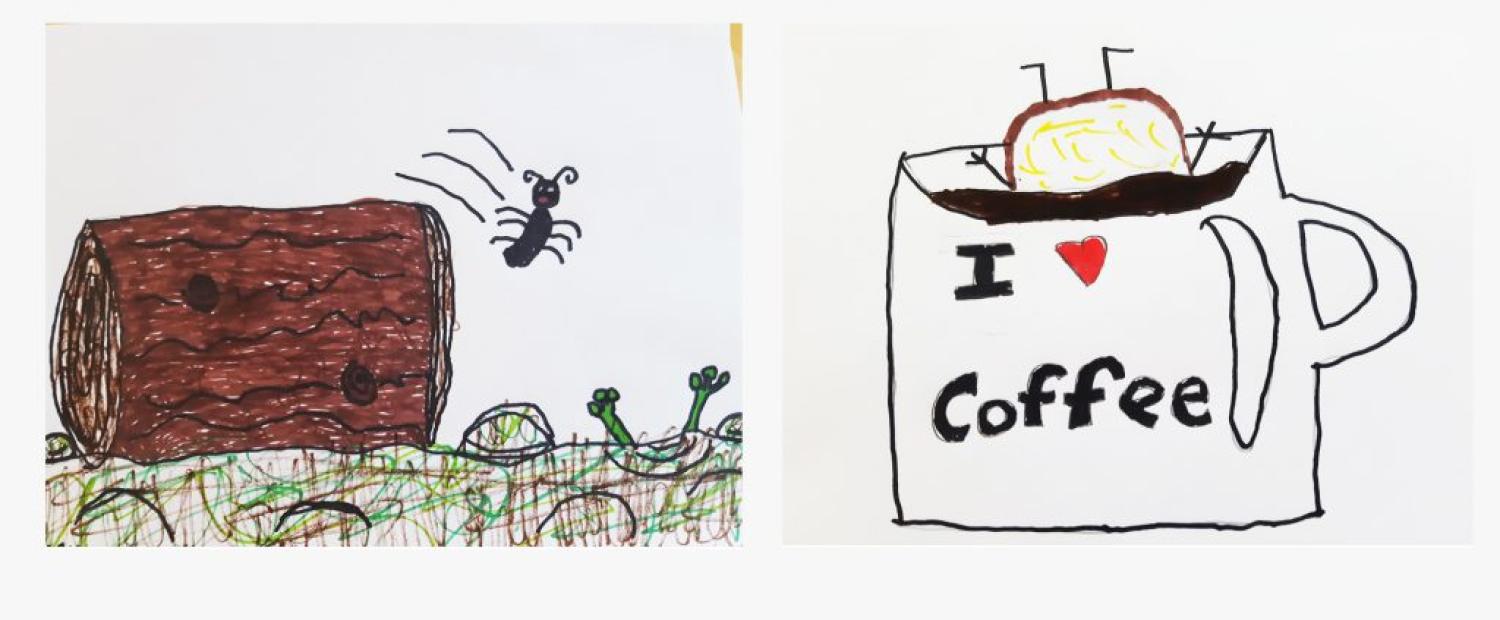

Having taken a number of graduate English classes from prestige-laden professors at Yale, I am well-equipped to provide erudite commentary on these two poems. As similarly sophisticated readers will have noticed, a rich supply of themes and patterns unite these lyrical compositions. In both of these verses, the poets wrestle with the unintended consequences that so often characterize the fate of aspiration and ambition for humans, amphibians, or even grain-based products. We think we are just going to jump on a log or stand on our heads, and instead we set in motion a chain of events that deliver us to an unchosen immersion in fluids. Similarly, both poets pay tribute to the force of gravity as a factor that scrambles the alignments and arrangements that we mistakenly take to be predictable and even foreknown, with a fall suddenly reminding us of our precarious and uncertain positioning in life. Noting these striking thematic similarities (and others too numerous to mention), you might begin to think that these limericks—both beautifully illustrated—are the creation of authors who are, in some way, kin.

Perhaps sisters?

How’d you guess?

A Promise, Fulfilled

Here is the promise I made in last week’s “Rodeo” post:

As a commemoration of its one-year anniversary, “Not my First Rodeo” will present the most charming and spirit-lifting collection of words ever sent out into the world by the Center of the American West. I make this promise with confidence because I have recruited two talented and energetic co-authors who will be making their literary debuts.

As you can tell from the opening limericks and their accompanying illustrations, I am delivering on that promise by recruiting my two great-nieces as co-authors. Piper is ten, and Daisy is eight.

In other words, you can now remove “the decline of the limerick” from the list of troubles that come to your mind when you consider the prospects for the twenty-first century.

Just before we return to the charm, wit, and energy that run through this blog post, I will make that return all the more welcome by putting forward a somber statement.

As the twenty-first century unfolds, there are reasons to think that babyboomers are not going to register in history as impressive performers in the sport of intergenerational transition. For the members of my demographic cohort who are fortunate enough to be in good health, the Spring of 2021 is an auspicious time to try to improve the performance ratings that posterity will give us.

My success in recruiting and welcoming the next generation of limerick-writers may not seem like the “make it or break it” moment for the future of the planet. But as this “Rodeo” post shows, my efforts in this particular arena are delivering better results than many other undertakings in intergenerational succession these days. In truth, I would do a disservice to people of every generation—including those not yet among us—if I didn’t put this success on permanent public display.

How This Recruitment Occurred, and What Lies Ahead

I have long known that my great nieces (and my niece, whose gift with words I would like to present in a future “Rodeo” post) have very lively minds and enjoy the company of words. But for reasons that remain hidden to me, I never once thought to myself, “You’d think a great aunt would prove her ‘greatness’ by introducing these young folks to the art form of the limerick.”

The route to this recognition was not linear, to the point that I was not actually the one who provided that introduction.

Here’s what happened.

A few weeks ago, in a phone conversation, my sister Sunnie (Daisy’s and Piper’s “Grammie”) and I got to talking about a man who held an important administrative position in our hometown’s schools. This man had an unusual personal quality. This statement might stir up curiosity in readers, but I am compelled to stay within the bounds of small-town discretion, concealing both this man’s name and his unusual personal quality.

For now, I will just say that reminiscing about this well-known figure in our hometown stirred up quite a bit of merriment. Early the next day, Sunnie realized that this merriment had turned into a limerick. This was not her maiden voyage in limerick-writing, but she estimates that five or six decades had passed since her last venture into this literary genre.

And now for a shamelessly manipulative act of building expectation and curiosity in readers.

If you want to see the result of Sunnie’s homecoming to the land of the limerick, and also if you want to get a hint as to which “unusual personal quality” made us laugh so hard, you have to keep reading until the end.

(No scrolling! Keep reading!)

One thing then led to another, and Sunnie was inspired to build training in the composition of limericks into her homeschooling curriculum for her grandchildren. Meanwhile, on a parallel track, I had been on a fruitless quest to think up some amusing and energetic way to observe the one-year anniversary of “Not my First Rodeo.” As this limerick renaissance took off, the quest was resolved.

This “Rodeo” post has seven parts that proceed along at a brisk pace:

First, two limericks I wrote about my co-authors.

Second, the debut of Piper and Daisy as prolific writers of limericks, a literary event that now registers as a spectacular episode, setting an example for the planet, in babyboomer intergenerational transition.

Third, a symphony of quotable statements in which Daisy and Piper capture the satisfaction and the joy that limerick-writing provides to its practitioners.

Fourth, the Bulkly Tribute, a celebration of another novel (in every sense of the word) writing project that my sister and her grandchildren are now completing.

Fifth, a visionary prescription for writing instruction in childhood, offering a magic combination of precise word choice, vocabulary expansion, brevity, and fun.

Sixth, scenarios for considering words to be our friends, with guidance on how humans can enjoy the company of words, and how words can enjoy working with us.

Seventh, Sunnie’s initial verse on the “unusual personal quality” of our townsman, along with examples of her continuing commitment to the well-being of the limerick.

Part #1

Limericks by the Great-Aunt Who Has the Luckiest Surname Ever,

and Who Has Had Equally Good Fortune in Kinship with Verbally Agile Great-Nieces, Niece, and Nephews

A wondrous young person named Daisy

Is now writing limericks like crazy.

She thinks all the time,

Quite often in rhyme,

With a viewpoint that never goes hazy.

With a gift for words that’s uncanny,

Encouraged by her exuberant grammie.

Piper writes verse that’s a hit,

Filled with humor and wit,

Storing insights in each nook and cranny.

Part #2

The Literary Debut of Two Authors

Limericks by Daisy and Piper

I once was the owner of poodles.

My poodles would only eat noodles.

I tried all in my house,

Even added a mouse,

But my poodles had left by the oodles.

There once was a man who would sneeze

Each time that he said, “If you please.”

When he said an “Achoo,”

Then off flew his shoe,

And he finished it off with a wheeze!

There once was a great big old lion

And his name was Catastrophe Ryan.

When he jumps in his tracks,

He is looking to scratch.

And to tell you truth, we’re not lyin’.

At the farm was a significant pen

That housed a magnificent hen.

A fox came to check it,

But the hen chose to peck it,

In seconds, the fox ran away in just ten.

Limericks by Piper

I know a man named my Daddy.

He has a fine aunt named Aunt Patty.

She speaks with long words,

That no one has heard;

My Daddy’s a super great laddie!

One day there was a black pen,

And his friends called him Barry Ogden.

On the day of his birth,

He was blessed with great mirth,

But the first thing he wrote was not then.

I am in need of a warm winter coat

When I go out in my cold little boat.

Or else I shall freeze

Each time there’s a breeze,

And be unable to cross a small moat.

Limericks by Daisy

There once was a man who was funny,

So he went to the store for a bunny.

He could only buy half,

So there was no way to laugh,

Because he had not nearly the money.

There once was a half of a cookie,

Who decided to become a new rookie.

He joined with a team,

His chin up like a beam,

And he called to his friends, “Lookie, lookie!”

There once was a girl with a bonnet

That had flowers and ribbons upon it.

It was lost in the hay

On a very sad day,

So she decided to write a nice sonnet.

Part #3

Quotable Remarks in which Piper and Daisy Convey the Experience of Writing Limericks

- Sparkles of ideas fall around you all the time. If you can get hold of a few and put them into a limerick, then you have it forever, and now the ideas can’t escape.

- We can write a limerick if we just think up a few rhyming words. Then they pretty much find their own way into a limerick.

- A limerick is like a container where you can keep words safe so they won’t ever get lost.

- Writing limericks is like building your own amusement park.

- Limericks are easy to remember. Maybe we can put the multiplication table into a limerick.

Part #4

The Bulkly Tribute:

A Novel Way to Defy and Exceed Standard, Strict Limitations on Having Fun While Revising and Proofreading

I might strike some people as an adventurous sort, but that is only because they haven’t met my sister. To mention one notable example of things she does routinely that I will never do at all, she has made a couple of voyages in the South Seas, traveling by cargo ship.

Meanwhile, back at home, she had the occasion to look over a big collection of books from the 1930s and 1940s, looking for a book that Piper and Daisy would enjoy reading with her.

A book called Mr. Bulkly on a Cargo Boat won first place in this unusual literary competition. This was a fictional work by a man named Hugh Lound, who arranged his novel as a first-person tale told by Mr. Bulkly.

So Piper and Daisy and their grandmother undertook a close reading of Mr. Bulkly on a Cargo Boat. They all found reading this book to be so fun that they hoped it was part of a “Mr. Bulkly” series.

But it wasn’t.

When Mr. Bulkly disembarked from the cargo boat, he implied that he was looking forward to his next journey.

But then he went silent.

What to do?

At this point, many fans would have given up.

Not these fans.

They resolved to write the sequel, Mr. Bulkly and the Grand Reunion.

Here was the authorial process they followed, which I will lay out very clearly on the assumption that many others are going to want to imitate it.

- The writing of each chapter began with a brainstorming session, in which Daisy and Piper conjured up what Mr. Bulkly and his comrades would do in that chapter.

- My sister kept track of these ideas and then wrote a draft of the chapter. But—and this is very important—she dashed this off, without taking a moment to review the result and certainly not to proofread it.

- Piper and Daisy then put on their hats as editors and got to work on a critical reading and careful proofreading. (I actually don’t know if they have “editor hats,” but this is a useful idea to keep in mind for the 2021 Holidays.)

- Finalized and polished, the chapter was then carefully stored, and the brainstorming moved onto the next chapter.

I celebrate all four steps, but it is Step 3 that could make me weep.

I started grading papers in 1974. Over nearly fifty years, I have read wonderful student writing. But my reading experience has often led me to say to myself, “Something has gone wrong here, and I am not sure how to fix it.”

In that context, when I think of two young children, regularly engaged in editing, proofreading, and generally scoping out opportunities for improvement in a written text, I feel as if I am having a dream that is soaring past my wildest hopes.

But Mr. Bulkly made this dream come true.

And now for a spectacular statement that the authors reported to me: As they became immersed in the writing process, they realized that they had spent so much time with Mr. Bulkly that when they spoke, they sounded just like him.

That Mr. Bulkly was one lucky fictional character.

Here are two summations-in-verse (the first one by me, and the second by my sister) of this extraordinary literary enterprise.

As you know from the surname of Bulkly,

This man didn’t qualify as “sveltly.”

Since he’s been given new life

And—very possibly—a wife,

He’s lost every right to be sulkly.

The first Bulkly book was so clever,

We grieved for what seemed forever.

Then to work we began

And what you hold in your hand

Is a reminder to never say never!

Sorry, readers, but the phrase, “what you hold in your hand,” cannot be literally true just yet. But opportunities may be on the horizon.

Part #5

We Interrupt this Good Time for Recommendations for Curricular Reform

I do not know much about the techniques and strategies for the teaching of writing in 2021, but I feel certain that assignments to write limericks and sequels are absent from most lesson plans.

So here’s what I’m thinking.

Even though I believe many teachers work persistently and heroically to encourage good writing, the quality of the papers submitted by college students is not a feature of societal success.

Why?

Maybe because the requirements of standardized testing foster an environment that seems actively hostile to good writing—and even more hostile to enthusiastic writing. Maybe because there is so much subject matter to cover in a school year that there is little time left for the cultivation of writing skills. Since research is constantly expanding the material to cover in many areas of study, lesson plans that were already bursting at the seams can’t stretch much further.

This leads to one unmistakable conclusion: teaching strategies that embrace brevity are the great hope for the future.

Reading a paper closely, offering suggestions for improvement, takes forever. And, as evidence has repeatedly proven, few students have acquired a willingness to work their way through that labyrinth of commentary, improving as they go.

Ready for the recommendation for curricular reform?

Consider the enormous advantages that would come into play if we put limericks at the center of writing instruction. Having on hand, at the moment, a multiplicity of samples on which to perform word counts, I can offer this good news with precision: the average limerick is only thirty words long.

Here’s the punchline: this brevity would permit teachers and students to concentrate on 1) figuring out what is essential to say, and 2) working hard to choose exactly the right words in which to say it.

Having spent nearly a half-century reading student papers (well, OK, I actually did a few other things as the decades rolled by), I can identify with certainty the two greatest weaknesses of the writing submitted in college classes: 1) not having figured out what is essential to say, and 2) not working hard to choose exactly the right words in which to say it.

Make limerick-writing the core of writing instruction, and the quality of life for teachers will soar, even as student grades undergo an entirely earned and deserved inflation.

And we cannot omit Mr. Bulkly’s contribution to curricular reform.

Let’s add this to our recommendation for curricular reform: 1) Pick a book that students, more often than not, enjoy reading, and 2) assign the students to write a sequel for that book.

Of course, given our embrace of the value of brevity, we should offer options that are far less demanding than writing a whole new book. Sticking with the program of selecting an essential message to convey and choosing exactly the right words to capture that message, we could assign the students to write—and rewrite and then rewrite again—a one-page summary of the sequel they propose. Needless to say, we should not surrender an inch on the continued obligation to edit and proofread those drafts.

Sequel-writing would have been a perfect activity to take up during the lockdowns of the pandemic, but the opportunity remains entirely viable for deployment in households as well as schools. Following the instructional precedent set by Mr. Bulkly and The Grand Reunion, teachers—and parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts, great-uncles and great-aunts—have an arena of adventure open to them. Identify a shared enthusiasm for a particular book, and you are launched on a merry intergenerational collaboration, yielding a product that will keep delivering pleasure whenever it is pulled out of the past and reactivated to enliven the present.

Part #6

Words as Our Pals and Collaborators

At my request, Sunnie told Piper and Daisy about a document called “Limerick’s Rules of Verbal Etiquette.” Even though only a very small population has ever read this document, I have always thought that these rules could be really useful as guidelines on writing. And now that Piper, Daisy, and Sunnie have read this text, its readership may have just doubled, a geometric increase which seems very auspicious indeed.

Perhaps inducing another geometric increase in readership, you will find “Limerick’s Rules of Verbal Etiquette” in the Appendix.

Sunnie first asked Piper and Daisy to ponder the stated premise of “Limerick’s Rules of Verbal Etiquette:

Words are our friends, and people should not put their friends in awkward positions.

She then invited them to write their own scenarios putting that premise into operation.

Here are the results.

Words Want Us to Play with Them

by Daisy

Words are great comedians. For example, we can have fun with waist and waste. Waist: a part of our body is our waist. Waste: waste like wasting food or throwing it away. (We would never want to throw a part of our body away. We don’t want to waste our waist.)

Also flour and flower. Flour would be the cooking ingredient, or a flower would grow in your garden. (You could never make a bouquet of ground-up flour or you shouldn’t put a flower from your garden in your cake. You could put it on your cake, but don’t eat it.)

The brave knight traveled through the night. It was enough to tire him because he had to change the tire on his horse, and then he got kicked, and it made him scream, and then he was hoarse.

Well, that settles it! Goodbye for now!

A Conversation with Words

By Piper

“Hello, Reader! Today we are going to have a conversation with words. Here we go!”

“Are you ready, Words?”

“Yes!”

“We gotta work together now . . . “

“Excuse me. You mean ‘we have to work together now.’”

“You ain’t gonna stop corre . . . “

“That is, ‘You are not going to.’”

“I don’t wanna get corrected no mor . . .”

“Say, ‘I do not want to be corrected anymore.’”

“Sorry.. I . . . do . . . not . . . want to . . . be rude.”

“You did it!”

“Yay!”

I learned not to get too upset and ignore what someone is teaching me, especially when it comes to being nice to Words and having them as friends.

Part #7

The Acorn Does Not Fall Far from the Tree:

Limericks by Grammie Sunnie

My sister’s last name is fortuitous.

Its value has really come through-to-us.

The lines we compose

Blossom like a rose.

I think they reflect at least two of us.

I am radically tired of my phone.

It never just leaves me alone.

When it dings in the night,

I awake with a fright,

But I’m left with merely a groan.

When all of us sing karaoke,

Some songsters incline toward the croaky.

Yet with some voices bad,

And songs super sad,

They somehow still sound okey-dokey.

A limerick brings clarity to life,

It cuts through the fog like a knife.

If you’re leaning toward sadness,

It shifts you toward gladness,

A tool that spares us all strife.

And now the long-awaited reveal of Sunnie’s limerick about the “unusual personal quality” of a leading citizen in our hometown, with a change of name to protect us from (what would be somewhat vague) charges of libel and from the resentment of any of his descendants:

Mr. Watson had an issue with toes,

The nature of which no one knows.

Haphazard or tainted,

Thickened or painted,

On his secret, we must not impose.

A Concluding Demonstration that It Is Not Easy to Tell Babyboomers,

“OK, You’re Through Now!”

Yes, of course, I could and should quit here, but Part #3, Quotable Remarks in which Piper and Daisy Convey the Experience of Writing Limericks, inspired me to do what I had never done before: to write a short statement on why I have loved writing limericks for fifty years, a custom that was already in full swing when I met Jeff Limerick. (Just a hint to students: writing limericks is a great way to present a deceptive appearance of rapt attention in lecture classes).

Why You Might Want to Join Piper, Daisy, Sunnie, and Me in Writing Limericks

Of all the ways you can spend your time when the world is not making sense, writing a limerick is the activity most likely to permit you to say to yourself, “I’ve got it now!”

APPENDIX

Limerick’s Rules of Verbal Etiquette

Words are our friends, and people should not put their friends in awkward positions. When an author mistreats them, words and sentences feel discomfort, even pain, and certainly resentment. And yet, unlike human beings, words have no capacity to hold a grudge. As soon as the writer relieves their misery, words and sentences will work wholeheartedly for the writer’s cause. The empathy, commitment, and attention that produces good relationships among people match, exactly, the qualities that build friendships between writers and their words.

- Weak subjects and verbs tremble and strain to hold up under the weight of important content. Kindness often requires you to relieve them of this impossible task and to replace them with strong subjects and verbs.

- When the passive-voice verb tries to drain the energy from sentences, you must rescue the sentences and bring them back to life with an active verb.

- Sentences want to be limber, flexible, sleek, and agile. Often, this means that they want to be small and manageable in size. They do not want to be bulky, awkward, and overweight, nor do they want to be overloaded or overdressed. They especially resent having to carry around an excess of prepositional phrases and polysyllables.

- A sentence fragment knows and resents the fact that no one is going to listen to it or have any respect for it, because it lacks either a verb or a subject. Kindness requires you to move fast to transform a sentence fragment into a whole sentence.

- Words hate it when you ask them to convey unclear thoughts or no thoughts at all. They are very uncomfortable when readers ask them, “What on earth are you trying to say?” and they have no answer to give. They feel, at that moment, all the misery of a person who has been introduced to give a speech and who does not, in fact, have a speech to give. The good news is this: if you place your words in sentences with clear and direct content, they will gratefully do everything they can to support your cause. But if you force a word to take its place in a confusing sentence without a clear message to convey, it will—in the manner of a baby seal or puppy—look at you and say, “Why would you want to hurt me?”

- When you ask a group of sentences to form a paragraph, they expect to arrive in the paragraph and find that they have a lot in common. They expect, moreover, to find that one sentence is in charge of the paragraph, and ready to introduce the other sentences to each other and to remind them why they have all gotten together. When, instead, they show up in the paragraph and realize that they have nothing in common, they are as uncomfortable and lonely as people who have arrived at a party where they know no one, and the host does nothing to put them at ease

If you find this blog contains ideas worth sharing with friends, please forward this link to them. If you are reading this for the first time, join our EMAIL LIST to receive the Not my First Rodeo blog every Friday.

Photo Credit:

Banner image cartoons and limericks courtesy of: Piper (frog) & Daisy (bread)

“Mr.Bulkly on a Cargo Boat” image courtesy of: abebooks