Let There Be Accountability on Earth, And Let It Begin with Me (And Millions of my Fellow Citizens)

For longer than we may have realized, we have been living in desperate times. Nonetheless, many Americans have been lucky to live in circumstances that permitted them to pay only sporadic attention to our chronic calamities in the arenas of public health, employment, social conflict, governance, and politics.

That changed on the afternoon of Wednesday, January 6.

After an incendiary speech by the most powerful man in the world, a mob took over the United States Capitol, and the desperation of these times flared past anyone’s capacity for dismissal.

Complacency has left the building—not just the building where the United States Senate and House meet, but all the buildings where we live, work, and try to hold things together.

In what was certifiably the most trivial mishap of a calamitous week, the Center of the American West experienced a bout of “technical difficulties,” and sudden historical change ran over us.

We had been working ahead of our usual weekly schedule. So I finished writing the “Not My First Rodeo” post, at 8 a.m. on the morning of Tuesday January. 5. The piece was laid out and locked into digital “launch mode” by late afternoon on Tuesday.

As the title of the post—“The Promise and Peril of a Positive Attitude on the New Year”—signaled, the essay walked its own tightrope between hopeful humor and a realistic assessment of the dilemmas that did not come to a halt at midnight on December 31, 2020. On the contrary, the year 2021 held a weak claim on the status of a fresh start and a new beginning.

And then, on Wednesday, all hell broke loose in Washington, D.C. Broadcast (with a certain unavoidable slimness of the "broad" part) out into the world on the morning of Friday, January 8, what I wrote about having a “positive attitude” looked like a failed attempt at the denial and dismissal of the calamity at the Capitol.

Here’s where the technical difficulties came into play.

None of us knew how to add a preface to my essay to explain its timing, nor how to replace it with a statement that responded to the cataclysm that had befallen the nation.

Hence, the smallest-scale calamity of last week: the author of “Not My First Rodeo” seemed wildly out of touch with reality.

Probably not for the first time.

The Tightrope as a Workplace

Choosing a tightrope as a place to take a stand might seem like a very poor decision. But when I defined the Center of the American West as an organization committed to bipartisanship, that IS exactly what I chose. The challenges presented by that choice have never been insignificant, but the events of January 6 increased their intensity almost beyond my comprehension. Planning and writing this “Rodeo” post, I have felt as if I were in the shoes of the fellow who is defying gravity on the banner above.

When it comes to deciding on the next step, a person who has taken her stand on a tightrope, particularly when no one got around to installing a net between her and the ground far below, has three tolerable choices when she considers next step: I can move forward; I can move backward; or I can stay where I am.

Maybe there’s a fourth option, or even a fifth one. I could call for a crane to perform an emergency rescue and remove me from my uncomfortable location. But taking that option would convey an all-out failure of nerve, a mental shift that would bring a tightrope-walker’s career to a sudden close. And, really, once the serious addiction to adrenaline has set in, any other career would seem insufferably dull.

To open the possibility of a fifth option, consider the very peculiar circumstances faced by bipartisan tightrope-walkers in recent years: while we are doing our best to stay upright and trying not to fall, the ringmaster of the circus in which we are performing has gone rogue, yanking erratically and wildly on the ropes that provide our precarious footing.

The fifth option: When the occasion warrants it, advocates of bipartisanship have a right—even an obligation—to reprimand a renegade ringmaster. “If you can’t stop yanking at that rope,” we are distinctively positioned to say, “you will forfeit your welcome in any arena where citizens gather to assess their challenges and work together to solve problems. You will retain your First Amendment right to shout whenever and whatever you like. But you will finally notice that the rest of us have left you where you are and moved on to another arena entirely. A faint trace of your agitated voice may reach us every now and then, but it certainly will not hold our attention.”

Since my intention with this post is to go all-the-way with forthrightness, I’ll declare explicitly what everyone has figured out: yes, this renegade ringmaster who is soon to change arenas is President Donald J. Trump.

In the passages that follow, I will tell a story about a trip to South Dakota where I learned two lasting lessons: one about the great pleasures of public speaking, and other about the ethical obligation to speak out, even when—especially when—staying silent would be far more comfortable. After that, I’ll present the understanding of bipartisanship that recent events have required me to rethink. And then, on the chance that I still have not exhausted the supply of adrenaline delivered by this tightrope-walking, I’ll challenge the statements that a number of my fellow historians have made in response to the Capitol insurrection.

Note to all: As always, I welcome appraisals of my performance on the tightrope of bipartisanship, as well as any useful coaching. I realize that the comment--“You should never have gone out on that tightrope in the first place!”—might come to your mind. In fact, it has come to my mind, but the idea of backing up on a tightrope presents itself as a change of course that I would not enjoy.

How The Capitol Takeover Reactivated a Lesson I Learned

In the Rural Heartland (Aka South Dakota) a Half-Century Ago

In 1971, as readers of “Not my First Rodeo” with unusually retentive memories may recall, I received my first apportionment of what Andy Warhol characterized as every person’s allotment of fifteen minutes of fame.

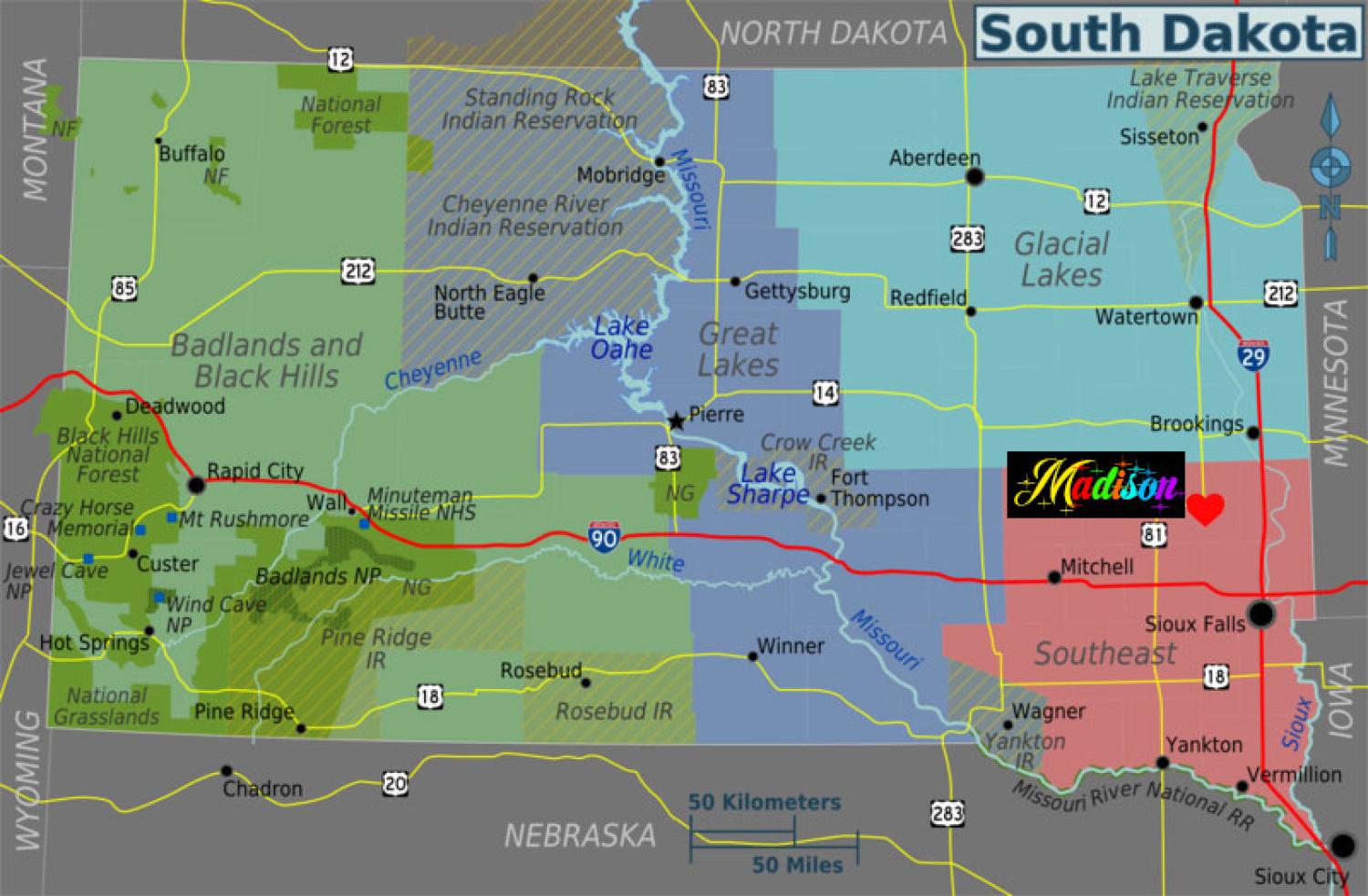

My first three minutes of the fifteen came with a lucky extension in time: I got to spend a week in Madison, South Dakota, my first trip to what I saw as the Eastern United States. (South Dakotans should not take offense at that phrasing. Remember, I was a Californian who had never been further east than my parents’ homeland of Utah.)

Gerry Lange, a professor of history at General Beadle State College, now Madison State College, saw me on CBS News and sent me my first-ever invitation to speak in a distant locale. This maiden voyage in public speaking was so much fun that it has made it nearly impossible for me, over the succeeding half century, to turn down a speaking invitation.

Gerry Lange was and is a remarkable person by every measure known to humanity. To cite just one example, at an overnight retreat we attended at the Catholic Church, the priest told us we were going to take a fifteen-minute break, during which we could “do whatever we wanted.”

Gerry Lange went to the middle of the room and did a headstand.

When asked why he did that, he answered, “The priest said we could do whatever we wanted.”

During my week in eastern South Dakota, I socialized at a wild pace. I gave speeches hither and thither. For the first time in my life, I saw baby piglets frolicking in a barnyard. I drank my share of Grain Belt Beer, and no one asked for my ID. When I told one of the founders of Prairie Village, Madison’s collection of historic buildings, that I was very scared about the sure-to-be-unpredictable changes of graduating from college and going to graduate school in the (actual) Eastern United States, this is what he told me: “Every winter, the ponds here freeze, and then in the spring, they break up. There’s a lot of cracking, and some of it is loud, and there are chaotic chunks of ice smashing up against each other. And then, one morning, we get up, and there’s just water and a smooth surface.”

When times in graduate school in New Haven were rough, I could think about ponds in South Dakota.

When my week in Madison came to an end and Gerry Lange drove me to the airport in Brookings, two of his children rode along with us. As we got close to the airport, Bobby Lange said that he had really liked having me visit. He said he wasn’t sure what he had that he could give me, but he did have a dime in his pocket, and he wanted to give me that so I would have something that would remind me of him.

My career as a talent scout for the gifted young got off to an early start. Roberto Lange, once known as Bobby, is now the Chief Judge of the United States District Court of South Dakota.

And now reader patience is surely fraying.

Our nation is in a desperate state, and I am telling you about a nice trip I took to South Dakota a half century ago.

Why?

First, I am providing the background on my lifetime inclination to steer clear of many of the antagonisms summed up in the phrase, the “rural/urban divide.” When I was 20 years old, spending a week in Madison, South Dakota gave me a lifetime inoculation against the cognitive affliction of seeing the plains states as “flyover country,” cutting me off from any temptation to stereotype rural people. The Red State/Blue State division will never narrow my expectations about where I am likely to have an extremely good time.

Second, on one evening during that visit, Gerry Lange did everything imaginable to prepare me for what I am confronting in January of 2021.

Gerry gathered a number of his friends and student for a discussion. We began by watching a filmstrip, one of those technologies of ancient days where you listened to a recording and advanced the projector from one image to another. The words we heard in that filmstrip appear now in the United States Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C. They were written by a German Lutheran pastor after World War Two. I was born in 1951, and periodically, I remember that World War Two ended just six years before I was born. The words I heard that night in Gerry and Alice Lange’s farmhouse had been written only a few years before I was born. The catastrophe that brought them into being was not lost in the mists of time. It was recent.

Here are those words:

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Given our host’s character, we were not permitted just to say, “That was interesting,” and shift to more comfortable topics. Instead, Gerry kept us in a discussion, reminding us that the words we had heard might become very relevant at some unknown point in the future.

A dedicated teacher and a committed public servant, Gerry Lange served for two decades in the South Dakota Legislature. He is ninety-two years old, so it is possible for me to say this to him now.

I heard you, Gerry. Now I am speaking out.

Retrofitting Bipartisanship for Changing Times

A quarter-century ago, I adopted a bipartisan stance for myself and steered the Center of the American West in that direction.

Why did I make this maverick choice?

Here are three reasons.

- The enterprise of political polarization and reciprocal demonization struck me as overstaffed. If I didn’t change course, it seemed clear that I would disappear into the throng that was ardently preaching to choirs, reinventing wheels, and taking coals to Newcastle (or Gillette, Wyoming).

- Despite my best efforts, I could not avoid the recognition that visions and ideals that had seemed utterly convincing to me at college had failed to deliver their intended benefits; indeed, in some instances, they had delivered exactly contrary results.

- I finally accepted the weight lowered onto my shoulders by my history classes in college and graduate school. Professionally, I could not escape the obligation to pay attention to multiple points of view. If I placed the people of one sector of society in the past at the center of my attention, and if I only read their records and scrupulously avoided the records of the people who lived at the same time and utterly abhorred the people I had chosen as my focus of study, my professors would have corrected my course—forcefully. So, to use one example, the full weight of the historian’s burdensome obligations landed on me when the Center of the American West brought the former Secretaries of the Interior to CU for the “Inside Interior” series. Inviting these men to visit Boulder, I could not even begin to justify bringing only the Secretaries whose policies had particularly pleased me.

- An incurable allergy to boredom proved to be the tipping point. In a couple of decades in the academic world, I had taken part in so many conversations with the politically like-minded that I thirsted to hear some new opinions and perspectives. “New” meant many things, but “conservative” figured prominently in that category.

But then came the tough question: what did it mean, in day-to-day practice, to hold responsibility for a Center devoted to bipartisanship?

Improvising away, I decided it meant that I should take the role of a moderator bringing together people who would otherwise never engage in direct and forthright discussion.

This was not going to work if I clearly preferred people who supported one position over people who supported an opposite position.

Bipartisanship was an essential pillar for any claim I could make for authority and credibility as a moderator. So I purposefully surrendered my right to endorse candidates or advocate for initiatives. I thought that stance was necessary if I wanted to persuade people who disagreed with each to trust me and to agree to have me occupy the seat in the middle.

My improvised customs fared well for a couple of decades. But the Capitol takeover on January 6 pushed me all the way to a recognition that had been hovering at the edges of my mind.

I had gone overboard in my devotion to moderation.

For years, the word “moderate” was my touchstone. I adopted moderate positions on issues charged with conflict. I seized every opportunity to serve as a moderator. Racing from activity to activity, I caught only glimpses of an uncomfortable possibility: unless an advocate for bipartisanship permits herself to speak in forceful opposition to people who are relentless in their determination to prevail with “no holds barred,” “take no prisoners” conduct, bipartisanship has no champion.

Of course, figuring out who has, by an unrestrained attack on civil exchange, earned “the forceful opposition” of the advocates of bipartisanship is an unending conundrum. As we have limitless opportunities to observe in these times, one person’s stalwart defense of truth and virtue is almost sure to be another person’s unconscionable betrayal of truth and virtue. And yet navigating through these configurations of antagonism is the terrain where the card-carrying practitioner of bipartisanship has an advantage: a moderator must be adept and at ease in replacing her own first response (“That statement can’t be right! I’ve never agreed with any such thing in my life!”) with curiosity (“I’m not sure I find that convincing, but I should ask a few questions before I reach a judgment.”)

Accountability on a Personal Scale

This brings us to the Capitol takeover.

Shaken to the core by the images and stories of the violent takeover of the Capitol, I emerge as a renewed and refreshed champion and defender of bipartisanship. But here is the “reconfigured” part: I am facing up to the fact that an advocate of bipartisanship must speak out when public figures purposefully display their contempt for civil and respectful exchange among citizens and work to divide rather than to unify.

If they choose silence under those circumstances, supporters of bipartisanship betray their own cause, or at least serve it badly.

So I will now reactivate the lesson I learned in South Dakota by publicly performing an exercise in what I will call “dispersed and decentralized accountability.”

As a historian who is also an advocate of bipartisanship I should have begun speaking out when Donald Trump, as a presidential candidate, repeatedly showed his contempt for civil and respectful bipartisan exchange among citizens, spoke casually of violence as a way to express disagreement, and demonstrated his disrespect for fact and accuracy.

Whether candidates displaying such conduct are Republican, Democratic, Libertarian, or Socialist, my commitment to bipartisanship will shed credibility when I remain silent.

But I have no reason to back away from bipartisanship. My enthusiasm for moderating lively, open, civil discussions with people who occupy many positions on the political spectrum remains undiminished—and may even be enhanced.

A quarter-century ago, my conversations with principled conservatives played a key part in persuading me to “convert” to bipartisanship. These people have neither vanished nor abandoned their previous positions. They remain entirely on board with the bipartisan code of conduct for engaging in disagreement. They are loyal to the Constitution, determined to participate in a peaceful transition of presidential power, and they deplore the violence unleashed on January 6. And, even better, their ranks keep growing as younger Americans—some of them recently elected to Congress, some of them working in state election offices, some of them still seeking the affiliations and opportunities that will put them into action as fully engaged civic figures—go on public record in support of these principles.

I face no shortage when it comes to conservatives who I would proudly invite to take part in public programs at the Center of the American West.

Accountability Comes Home

Without a major upsurge in accountability and responsibility, the nation will be a very long time in recovering.

After four years with a President who habitually dodged accountability, all of us have the opportunity to contribute to the cause of a restored recognition of accountability in our own lives.

I will now apply this proposition to my professional roles as a teacher and a moderator of public discussions.

As a moderator, I have insisted on the civil conduct of speakers and audience members at public events. Over many years of hosting public events, I have had only four people break the rules of civil conduct, disrupting programs by shouting from the audience and making it impossible for the speakers to be heard. On those occasions, I have asked the disrupters to be quiet during the program, but to speak to me afterward at length. When they continued to shout, I had them removed by security. In the aftermath of the Capitol takeover, here is an aspect of those incidents that I did not pay full attention to: none of those people came near to advocating violence.

As a teacher, I have insisted that students cite evidence for their assertions, and I have required them to stay anchored in fact and accuracy. Over forty-five years of teaching, I have dealt with a few cases of student dishonesty, and I have held those students accountable. But I have never had a single student who treated fact and accuracy with indifference or disregard in the manner of President Trump.

Hence, accountability comes home: If I do not speak forthrightly about President Trump’s incivility and rejection of standards of evidence and fact, I forfeit the credibility and authority that are essential to the performance of my professional roles. If I were to exempt the President of the United States from the standards I have applied to students and to members of public audiences, I would fail at accountability.

A Stroll on Another Tightrope

In the last few days, a number of accomplished historians responded to the January 6 calamity with what quickly turned into a set piece of commentary.

If a public figure—perhaps the President-Elect—says that the disruptions at the Capitol “do not reflect true America, do not represent who we are,” then some historians, very rightly outraged by the insurrection and the President’s role in encouraging it, have been quick to respond, “Actually, the takeover did reflect the true America; that is who we are.”

Climbing back on my familiar tightrope, I offer my appraisal of that response.

Yes, beyond a shadow of a doubt, there have been innumerable historical episodes when white Americans engaged in violent behavior against legitimate governmental institutions or against ethnic and racial groups: Indian peoples, Blacks, Latinos, Asians, Jews, Catholics, and Muslims.

But casting the takeover of the Capitol as “just more of the same” may not register as the historical profession’s highest achievement.

My criticism deserves a strenuous round of debate, and nothing in the way of a quick ratification (as if such acquiescence presented much of a risk!). Here are my principal lines of dissent.

- History suffers distortion when it is painted with a broad brush. Portraying the nation’s history as an unbroken chain of horrific behavior by white Americans is over-generalization gone wild.

- In nearly every episode of horrific behavior by some white Americans, there were other white Americans in the picture who dissented from, opposed, and denounced this conduct, and sometimes pursued punishment for the perpetrators. From abolitionists standing up to slaveholders to lawyers practicing their profession on behalf of Indian tribal rights, from Army officers who expressed dismay over civilian attacks on Indian people, to white Americans who recognized the injustice of the Japanese American concentration camps, there is a historical tradition of white allies who may not have prevailed, but who existed. In truth, one could say that white historians in the twenty-first century, who are calling attention to the injustices inflicted over the course of American history, are the most recent inheritors of this tradition of white allies speaking out over the long haul of time. This tradition is obscured—or entirely hidden—by the broad-brush approach.

- The ideals written into the founding documents of the United States offer promises that the nation did not begin to put into practice for decades. And, in ways that we cannot dismiss or minimize, those promises still fall well short of realization. Denying the very existence of those ideals and the promises, or declaring them to be entirely hollow and meaningless, conveys a very understandable frustration and anger. But it also registers as an incomplete reckoning with history.

- This well-intentioned simplification of American history, aimed at raising a sense of outrage over the injury, inequality, and injustice that appear everywhere in the nation’s past, inadvertently affirms a sense of inevitability and fatalism. If American history only cycles through a set sequence of brutality and reassertions of white privilege, there is very little left for the well-informed to feel except resignation and defeat. I will bring the underpinnings of my comment to the surface: without any sense of progress or even the possibility of progress, this grim picture of American history writes a prescription for passivity and drift.

And then, still to be reckoned with, there is the conundrum of causality.

Historians can never be impulsive, casual, or impressionistic in their assessment of cause and effect. When we make claims of causality, we have to slow down our pace, note the uncertainties that appear in our evidence and in our reasoning, and phrase our assertions with care and precision. Most of all, we must be scrupulous in distinguishing causality from correlation, connection, or even coincidence.

Here is a statement that I believe respects those constraints on our professional practice.

Over the course of weeks, and at the rally on January 6, the President’s heated rhetoric and his persistent claims—made without evidence or proof—of voting fraud and a stolen election, hold a direct connection to the insurrection at the Capitol.

But here is a necessary follow-up statement: it will take a long time for historians to figure out exactly what words to use to state that connection with precision and certainty.

Currently, many verbs are used to characterize the relationship between Trump’s statements and the violence of his supporters at the Capitol. The word that seems to prevail is “incited” (as in “incited his followers to violent action”). But plenty of other verbs appear, disappear, and reappear in public commentary. Here are a few: “exhorted, encouraged, inspired, stoked, fomented, supported, enabled, influenced, inflamed, gave force to, urged, called upon, emboldened, galvanized, persuaded, swayed, motivated, reaffirmed.”

“Incited” might turn out to be the right word, but any of these others might qualify for use with future inquiry into cause and effect.

Here is my own reckoning.

I do not doubt that the President’s statements, over an extended period of time and culminating at the rally on January 6, played a significant role in setting the assault on the Capitol in motion. And yet, in a statement that many other historians might rightfully characterize as excessively cautious and restrained, I claim little understanding of the impacts of the President’s words on the minds of his diverse supporters, some of whom chose violence and some of whom did not.

Even as I admit that I do not know how the President’s words took hold in the minds of his supporters, the statements he made carry no implication of civil expression of dissent and discontent. When he told his supporters to come to Washington on the day that Congress was to certify the election results, the President said, “be there, will be wild!” On January 6, at the rally, he said, “We fight like hell, and if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.”

Historians I admire have insisted that it is a denial of the nation’s history to refer to the insurrection at the Capitol as unprecedented.

I part from that judgment.

Rather than seeing the violent takeover of the Capitol as one more episode in an unending string of such episodes, I see it as unprecedented.

Yes, there have been plenty of violent uprisings against authority in American history. But I do not know of any precedent in which a President of the United States deliberately stirred up an agitated crowd of supporters and told them to go to the Capitol, where all the Members of Congress were assembled, to overturn an election.

Here is the crucial benefit delivered by the appraisal that the Capitol takeover was unprecedented: That recognition defeats complacency.

Now that the takeover has occurred, we will never be able to say, “A violent attack on the nation’s institutions, performed—not by agents of a foreign power, but by American citizens—is unimaginable and impossible.”

Now that the precedent exists, we cannot repossess a form of reassurance that gave us comfort for decades. We can no longer tell ourselves, “This can never happen in the United States.”

It happened.

If you find this blog contains ideas worth sharing with friends, please forward this link to them. If you are reading this for the first time, join our EMAIL LIST to receive the Not my First Rodeo blog every Friday.

Photo Credit: banner images courtesy of: Wikimedia

Photo Credit: map images courtesy of: Wikimedia