“Next Stop: The Twilight Zone ” (Though We May Already Be There)

This highway leads to the shadowy tip of reality: you're on a through route to the land of the different, the bizarre, the unexplainable. . . . Go as far as you like on this road. Its limits are only those of mind itself. Ladies and Gentlemen, you're entering the wondrous dimension of imagination. . .Next stop: The Twilight Zone.

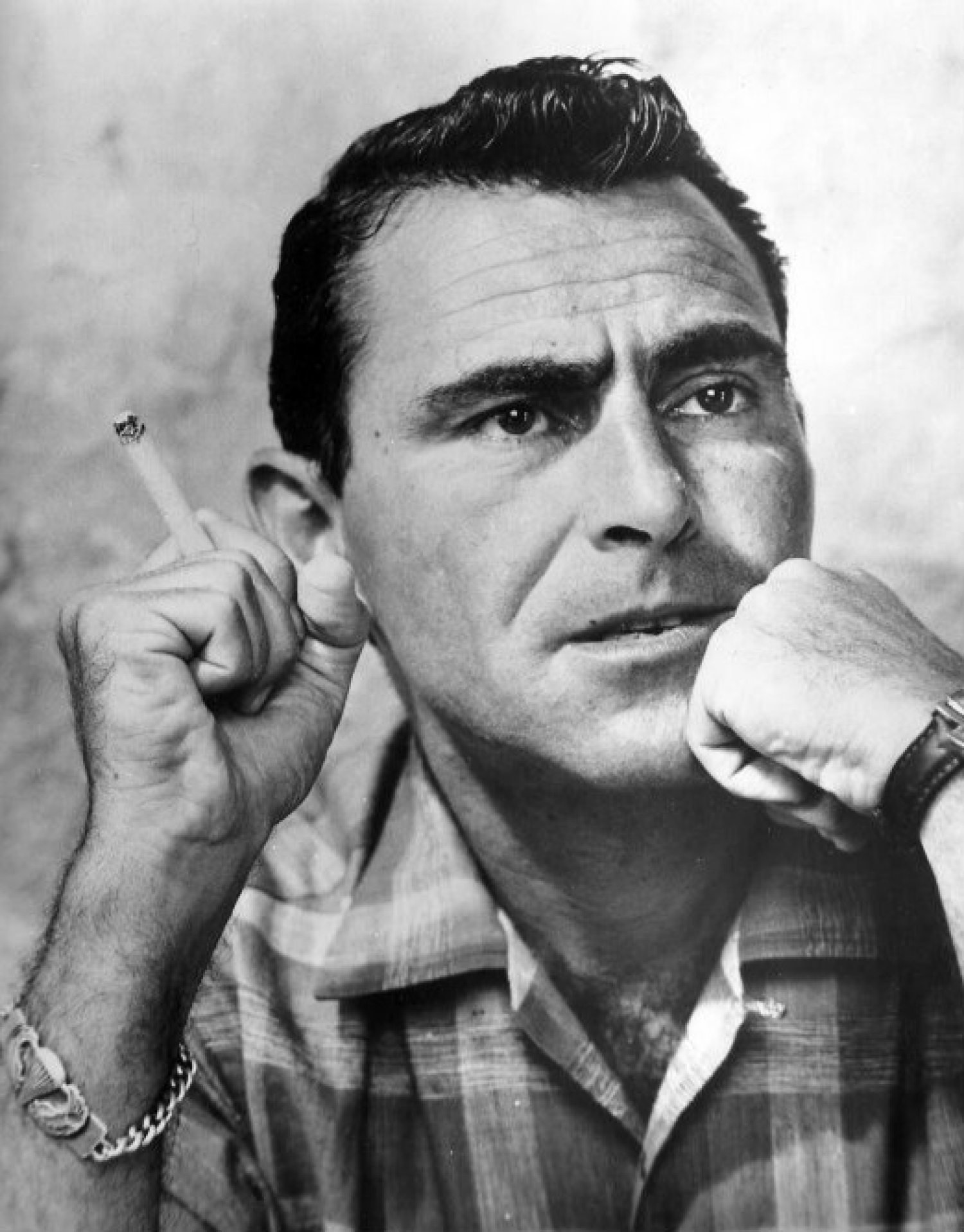

Rod Serling, welcoming visitors into the recesses of his own mind

If [The Twilight Zone] were merely a collection of bizarre stories with surprise endings, it would be long forgotten. It remains a touchstone of popular culture because its stories are as relevant today as when they first aired . . .

Nicholas Parisi, Rod Sterling: His Life, Work, and Imagination (2018)

No one could know Serling, or view or read his work, without recognizing his deep affection for humanity, his sympathetically enthusiastic curiosity about us, and his determination to enlarge our horizons by giving us a better understanding of ourselves. He dreamed of so much for us, and demanded so much of himself, perhaps even more than was possible for either in this time and place.

Eulogy for Rod Serling, by Gene Rodenberry, creator of Star Trek

Note to Readers: You are about to enter a zone, well worth visiting in 2020, where you will encounter many quotations from Rod Serling. In order to avoid endless repetitions of his name, italics will indicate the words that he spoke or wrote.

A Farewell to a Year Beyond Fathoming

After this post, “Not My First Rodeo” is going to take a break, returning on January 8, 2021. On the unlikely chance that this announcement throws you into panic or despair, here is reassurance: With a few brief postings in the “Did Anyone Else Notice?” series, you will still hear from me during this interlude.

But the fact that the “Rodeo” intermission will extend into 2021 forces the question: What is the right topic for concluding the extraordinary year 2020?

That is surprisingly easy to answer.

December of 2020 proves to be exactly the right time to testify to my appreciation for the heritage Rod Serling left us.

The Twilight Zone Shows up at Dawn

If I were not an early riser, my awareness of the gift that Rod Serling gave—to all of us living in these troubled times—might not have reawakened.

I start my days well before sunrise, and I sometimes stand in front of my house, trying to get my bearings for what lies ahead of me. But every morning, I first get reacquainted with the unprecedented disorder that broke upon the nation this year. I know that Covid-19 is on the loose, and I know that hospital wards are populated by people who are struggling to breathe. I know that the economy is in a disastrous state, and I know that unemployed people are struggling to pay their rent and to feed their children. I know that the nation is bitterly divided between voters who wanted Donald Trump to win and voters who wanted Donald Trump to lose.

But the pre-dawn light is gentle. The Flatirons are preening. No one is walking or bicycling or driving. My neighborhood is untroubled and tranquil.

And the collision—between the grim reality I am thinking about and the pleasant reality I am looking at—makes me feel that I have been transported to The Twilight Zone. In truth, there have been mornings when it would have seemed not entirely surprising to have Rod Serling appear on my sidewalk, cigarette in hand, speaking—very quotably!— of the wild turns of fortune that might be on my horizon.

As a kid, I watched The Twilight Zone religiously. The series started in 1959, when I was eight years old. My parents apparently didn’t know—or didn’t care—that this series was in a genre categorized as “adult fantasy,” and no one changed the channel to protect me. So I was very young when I got acquainted with the basic Twilight Zone scenario: everything seems very, very normal on the surface, and yet, just at the edge of perception, deeply improbable and implausible scenes are starting to unroll.

Regular viewers knew that episodes of The Twilight Zone would deliver unexpected twists and turns. This set us up to recognize that choosing complacency was perilous and sure to prove misguided. We knew we should refuse to be tricked by scenes of surface tranquility and well-being. And we also knew that we should not waste our time trying to rely only on reason, logic, and habit to predict the changes about to be unleashed.

The relevance of these lessons to the twists and turns of 2020 is far from subtle: stay on constant guard against complacency; recognize that no one can tell what is beneath the surface or around the corner; remember that when things seem very normal, this is very likely to be revealed as an early warning sign that something improbable, implausible, unprecedented, and bizarre is about to materialize. We should recognize that our perceptions—of people, places, and processes that we think of as normal and natural—are as predictable as they are untrustworthy.

And, when an episode ends, this will not mean that the initial conditions, once considered normal, will soon be—will ever be—restored.

Producing more than one-hundred-and-fifty episodes of The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling did everything imaginable to prepare us for the astonishing events that would transpire in 2020, forty-five years after his death. With his determination to point out habits of mind and taken-for-granted assumptions that served Americans badly, no one outperformed him in anticipating the world we now inhabit.

A Tested Soul as the Foundation for Authority

The tools of conquest do not necessarily come with bombs and explosions and fallout. There are weapons that are simply thoughts, attitudes, prejudices—to be found only in the minds of men. For the record, prejudices can kill and suspicion can destroy and a thoughtless, frightened search for a scapegoat has a fallout all of its own for the children . . . and the children yet unborn. . . . And the pity of it is that these things cannot be confined to The Twilight Zone.

This post is my first rodeo in the arena of quoting with unrestrained admiration from a celebrity. On other occasions, I have kept my distance from the assumption that fame bears a reliable connection to wisdom.

But Rod Serling presents a very different case.

Offering this tribute to him, I do not run the slightest risk of celebrating vacuous, airheaded, “lite” pronouncements by a media figure with an inflated sense of authority. On the contrary, Serling’s encounters with death and violence as a young man—really, a teenager—endowed his statements with a weight rarely equaled by writers or speakers who have tried to say to the public, “Watch out.”

Rod Serling served in the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 11th Airborne in World War Two. He was a paratrooper, but he was also an infantryman. In the Philippines, he participated in a very hard campaign to take the island of Leyte back from the Japanese. A month later, he fought in the very different, but also very dangerous, setting of city streets in Luzon.

Here are words Serling wrote, at nineteen years old, after the campaign on Leyte:

When we die we’ll all go to heaven,

Because we’ve done our hitch in hell.

Serling received the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star. A shrapnel injury to his knee left him with a lifelong limp.

For a time after he returned from the war, he was without a sense of direction. And then, enrolled at Antioch College, he decided to major in Language and Literature. The way to deal with his memory of war, he decided, was to “get it out of my gut—write it down.” As his biographer Nicholas Parisi put it, “From the time [Serling] returned from serving in combat, he wrote compulsively, continuously, perpetually aware of his own mortality, determined to carve I was here into the earth as often and in as many ways as possible.”

Did any of us, gathered around our television sets, entranced by The Twilight Zone, have any idea that the host and commentator was a military veteran who had seen the worst?

I [wanted to] convey what is a deeply felt conviction of the anguish of other human beings. This, I submit to you, is not a political thesis at all. It is simply an expression of what I would hope might be ultimately a simple humanity for humanity's sake.

Personal Gratitude for the Early Acquisition of an Aspiration

I try hard to remember and to acknowledge the people to whom I am indebted. But I owe a great deal to many people, and I also have a cluttered mind.

That is the only explanation of why I am so late in acknowledging my debt to Rod Serling.

At the beginning and ending of Twilight Zone episodes, when he framed the story with his comments, he gave me my first chance to see a public intellectual at work and to begin to think, “I’d like to do what he does.”

I cannot say, with precision, when I became aware that Rod Serling had (more or less!) said to me, “Here’s a vocation you might like.”

And yet I am entirely certain that, as a young child, I never said to anyone, “When I grow up, I want to be a public intellectual.”

There is one major reason why I never made that statement. Apparently, the very term, “public intellectual,” did not exist when I was a child. According to scholars who are way ahead of me in this inquiry, the phrase “public intellectual” did not appear (ironically enough!) in public until the 1960s. It didn’t make its first appearance in The New York Times, that seismograph of shifting intellectual fashion, until 1987.

But here’s what I could have said—and, really, should have said—in 1959: “When I grow up, I want to be like Rod Serling. I want to think as hard as I can, and if I come up with anything that might deepen and refresh civic conversation, then I want to be one-tenth as brave—and one-hundredth as creative—as he was.”

Near the end of this calamitous year 2020, getting reacquainted with the courageous critique he made of conventional thinking has made me aware how lucky I was to learn from him so early in my life, with this tutorial continuing for five years.

The five-year duration of the series was nothing to take for granted. In his television career, Rod Serling’s spirited and forthright principles regularly got him in trouble with censors and with sponsors. Twilight Zone’s success with viewers was never more than moderate, and the series, Serling’s biographer Nichola Parisi writes, “was almost constantly in danger of cancellation.”

And that made Serling’s strategy—for getting Twilight Zone placed on TV, for prevailing (for a while) over efforts to cancel it, and for holding onto sponsors—at once very clever, very practical, and very inspirational to aspiring public intellectuals of every age.

When newsman Mike Wallace asked Serling about his standing as television’s angry young man, Twilight Zone was just getting started. Serling told Wallace that, with this new series, he “didn’t want to fight anymore.” He didn’t “want to have to battle sponsors and agencies,” and so he was not going to invest time and trouble in taking up “controversial subjects.”

And then Serling put Twilight Zone to work on topics like nuclear war, McCarthyism, mass hysteria, violence, racial bias, hypocrisy, and any number of character flaws that Americans shared with human beings in general.

Telling stories in the genre of science fiction and fantasy made this possible. As Serling noted, “I found that it was all right to have Martians saying things Democrats and Republicans could never say.”

Rod Serling Talks Directly to Americans in 2020:

A Festival of Quotations

Whenever you write, whatever you write, never make the mistake of assuming the audience is any less intelligent than you are.

And this brings us to the best part of this final 2020 post of “Not My First Rodeo”: A Serling Quote-athon. In this compilation of passages, he speaks as if he were equipped for time travel with a passport, a boarding pass, and, regrettably, a return reservation. In a far more heavy-handed approach than he would ever have used, I have arranged these quotations with subject headings that, unsubtly, connect them to our circumstances today.

The Burden of Isolation

The barrier of loneliness: the palpable, desperate need of the human animal to be with his fellow man. [There is] an enemy known as isolation. [This very pandemic-relevant statement appeared in Serling’s commentary in the very first episode of Twilight Zone in 1959.]

The Destruction that Hate Wreaks on a Society and on Individuals

A sickness known as hate; not a virus, not a microbe, not a germ - but a sickness nonetheless, highly contagious, deadly in its effects. Don't look for it in the Twilight Zone - look for it in a mirror. Look for it before the light goes out altogether.

Fear, Suspicion, and Division

In this time of uncertainty, we are so sure that villains lurk around every corner that we will create them ourselves if we can't find them—for while fear may keep us vigilant, it's also fear that tears us apart—a fear that sadly exists only too often—outside the Twilight Zone.

Racial Bias

. . . the worst aspect of our time is prejudice. . . In almost everything I’ve written, there is a thread of this – man’s seemingly palpable need to dislike someone other than himself.

The Capacity for Self-Inflicted Misery to Make a Bad Situation Worse

According to the Bible, God created the heavens and the Earth. It is man’s prerogative - and woman’s - to create their own particular and private hell.

And (Maybe) a Lighter Touch: Consumerism and Advertising

It is difficult to produce a television documentary that is both incisive and probing when every twelve minutes one is interrupted by twelve dancing rabbits singing about toilet paper. . . . We're developing a new citizenry. One that will be very selective about cereals and automobiles, but won't be able to think.

An Earnest Protégé Gives Imitation a Try:

A Scenario

You unlock this door with the key of imagination. Beyond it is another dimension: a dimension of sound, a dimension of sight, a dimension of mind. You’re moving into a land of both shadow and substance, of things and ideas. You’ve just crossed over into… the Twilight Zone.

Contemplate the example that Serling set for us, and one lesson is unavoidable: a public intellectual should try to use every method in the tool kit to reach audiences. So I will now go all-out as a Serling protégé, giving it my best shot to create a scenario that will put reality on a roller coaster, fasten its seatbelt, and send it off on a ride.

Rescue, Just in Time

Living among us are thousands of people who repair and restore things that are broken. These people are capable and competent in ways that most of us are not. They fix cars, appliances, furnaces, roofs, roads, sidewalks, bridges, computers, plumbing, water supply systems, power-generating plants, electrical wires, and lighting fixtures. Their trucks appear on the streets near our homes, and these skilled people rescue us from dilemmas we could never manage by ourselves. Without these people, we would live in constant hardship and even in desperation. Many professors—and many public intellectuals—are pretty darned smart, but there is evidence to suggest that people who can repair things are smarter.

One of the most important services these skilled people provide to us is also the most uncomfortable. Sometimes, they have to say to us, “This cannot be fixed.”

Next Stop: The Twilight Zone.

What if the people who know how to fix things gave up on us?

What if they joined together in a vast association of the competent and capable, assessed the rest of us, and then informed us of their judgment and their demand?

Here is their statement.

Convening in The Twilight Zone, we offer you this ultimatum.

If you continue on your present course, the problems you have created for this nation will be impossible to fix.

If you want us to keep repairing and restoring the physical and material structures you rely on, then you will stop breaking the cultural and social structures that hold the nation together.

Surely Rod Serling would have found my attempt to follow in his footsteps to be short of success. But it is my dream that he would have said, “At least she caught on to the part about ‘unlocking the door with the key of imagination.’”

A Habit He Could Not Break

When he appeared on camera, Rod Serling almost always had a lit cigarette in his hand. By some estimations, he smoked four packs a day. When he was fifty, he had a series of heart attacks, and, right after cardiac-bypass surgery, a final heart attack killed him.

Usually, historians refuse the temptation of contrafactual imaginings.

But I cannot resist this one.

If Rod Serling had not smoked, we could have had decades more of his company and of his penetrating appraisals—at once merciless and kind—of our conduct.

Maybe, if he had broken free of tobacco, he would still be alive, and I would be doing everything I could imagine to get this “Not My First Rodeo” post into his hands.

Rod Serling would now be ninety-five, about to turn ninety-six on this Christmas Day.

Whatever else you will be doing in this unsettled holiday season, please consider joining me in quoting this man whenever the opportunity presents itself.

In any kind of priority, the needs of human beings must come first. Poverty is here and now. Hunger is here and now. Racial tension is here and now. Pollution is here and now. These are the things that scream for a response. And if we don't listen to that scream—and if we don't respond to it—we may well wind up sitting amidst our own rubble, looking for the truck that hit us - or the bomb that pulverized us. Get the license number of whatever it was that destroyed the dream. And I think we will find that the vehicle was registered in our own name.

Commencement Address at the University of Southern California; 1970

As long as they talk about you, you're not really dead; as long as they speak your name, you continue. A legend doesn't die, just because the man dies.

Publicity photo of Serling, 1959

If you find this blog contains ideas worth sharing with friends, please forward this link to them. If you are reading this for the first time, join our EMAIL LIST to receive the Not my First Rodeo blog every Friday.

Photo Credit: Image of Rod Serling courtesy of: Wikipedia