Staying in the Saddle for Eight Seconds

Where Limericks and Rodeo Coincide

The genre of comical verse

Inclines to the crude and perverse.

But in an era so ratty,

So messed-up and batty,

Could it possibly make anything worse?

In order to achieve a score that could lead to a win, a rodeo competitor must stay on a bucking animal for eight seconds.

As you keep that in mind, I invite you to contemplate a never-before-noted coincidence: eight seconds is exactly the time it takes to recite a trim and well-proportioned limerick.

And now for the real magic: used with precision and aim, eight seconds is precisely the unit of time needed to liberate historical knowledge from the tight spaces of conventional thinking.

You find that claim doubtful?

Hold on to your saddle.

Who Is that Old Guy on the Banner Above this Text?

Or

Which Lear Is That One?

Two memorable fellows named Lear

Held opposite positions on cheer.

Since the King one was scary,

And the Writer one, merry,

The difference between them was clear.

In the thousands of disputes that have raged over what should be taught in the public schools, no one has made a case for the urgent civic need for children to understand the difference between Edward Lear and King Lear. Nor has any advocate insisted on the extraordinary enhancement of capacity for self-expression that a mastery of the craft of writing limericks would give to the nation’s young people. No one else having taken up these causes, they seem to have fallen to me.

Among the characters who populated that historical zone called Western Civilization, King Lear ended up being much more famous than Edward Lear. Personally, I’m not sure that allocation of fame has proven to be entirely the best outcome for humanity.

King Lear was the Shakespearean character whose combination of rage and sorrow gave him the standing of the absolutely worst participant in generational transitions.

Edward Lear was on the other edge of that spectrum. He was an artist and writer who created funny poems and stories, accompanied by equally funny illustrations, that charmed children in his era and for decades to come. In 1846, he became widely known when he published The Book of Nonsense. If you are having a dreary day which you would like to brighten, here’s the ticket: start compiling your list of books, published since 1846, that should have been titled The Book of Nonsense, but were not.

Known as the originator of the genre called nonsense literature, Edward Lear is also recognized as the father of the art form we know as “the limerick.” Of course, literary paternity is quite different from the more physical and material form of paternity. Being the father of the limerick is less a matter of emulating Brigham Young or Rehoboam (who the Bible said had twenty-eight sons and sixty daughters), and more like being to a particular arrangement of words, what Johnny Appleseed was to fruit trees. Edward Lear never married and never had the literal kind of offspring, but he has done very well indeed with the literary kind.

If we return to the digital banner above this text, you will see that I appear there as the widow of Jeffrey W. Limerick, who would sometimes, at conferences and receptions, write on his nametag “The Other Limerick.”

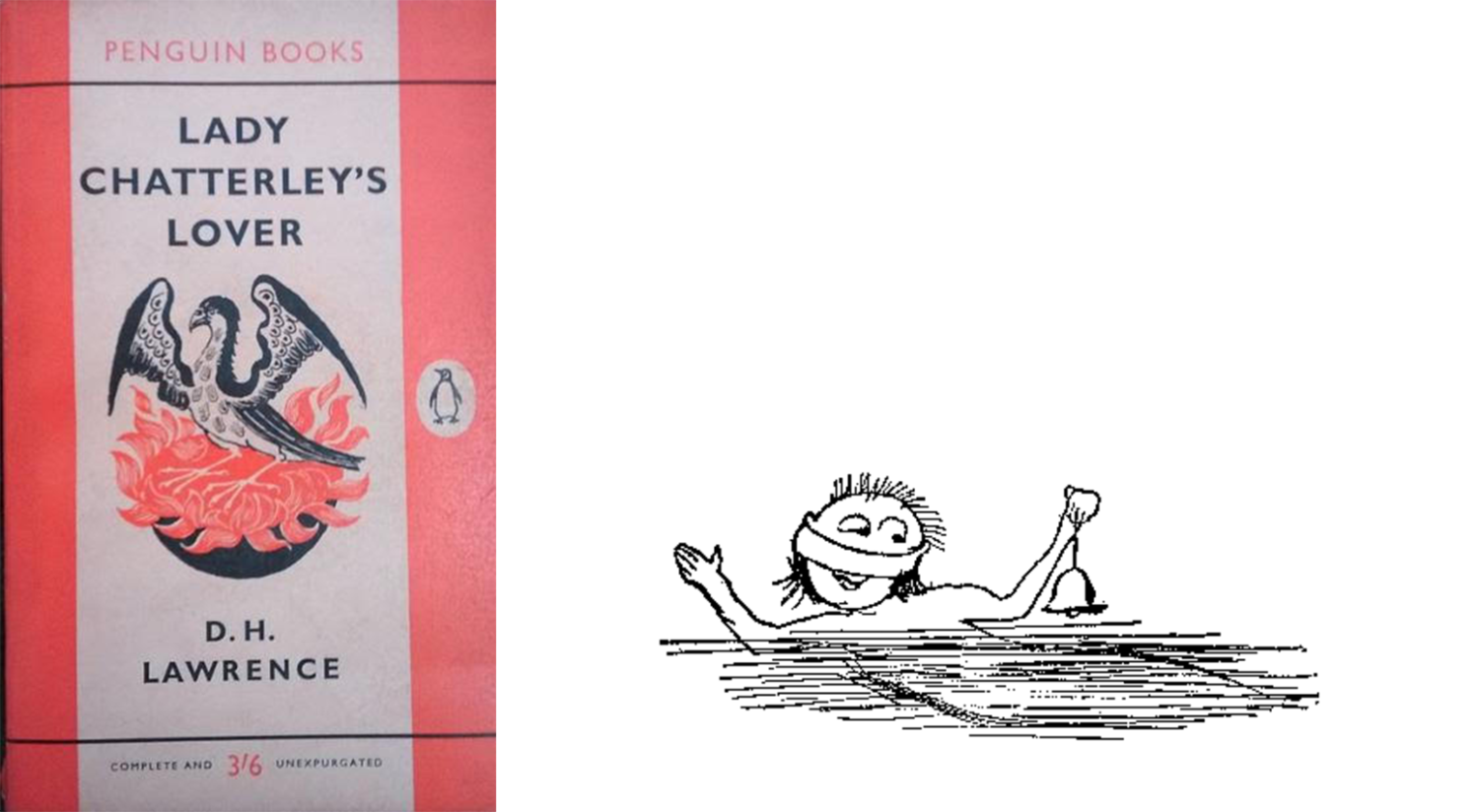

Even though the father of the limerick, Edward Lear, died in 1889, and I was born in 1951, I still feel as if I know him and I even feel as if I might, someday, co-author with him. But I should say, very clearly, that I am not going to propose the construction of an Edward Lear Monument in Boulder, although that would be an unusually fun dedication ceremony. Westminster Abbey got the jump on this line of commemoration: the Abbey has an Edward Lear Memorial Stone in Poet’s Corner. Consistent with his advocacy of utter nonsense, the Edward Lear Memorial Stone is evidently right next to the D. H. Lawrence Memorial Stone. In a certain sense, Lady Chatterley’s Lover reposes next to The Pobble Who Has No Toes.

The Limerick as the Historian’s Best Accomplice

I will now demonstrate what I meant by my opening claim: eight seconds offers just enough time to liberate historical knowledge from the tight spaces of conventional thinking. I will perform this demonstration by a maneuver of translation: I will make a point by expressing it in the language of limericks, and then I will make the same point by expressing it in the language of regular old prose with a tinge of the academic. The limerick will be very brief; the prose version, not so brief.

You can decide which works better.

And yet, in truth, the question of which works better is not really at issue. As the historian’s accomplice, the limerick gets the door unlocked so that historian can come in.

Metric Moments:

The Limerick Comes into its Own as a Force of Liberation

When the number of years that have passed since a historical event reaches a multiple of five or ten, the chances of the public expressing interest in this event undergoes a proportionate multiplication. Aspiring to put the art form of the limerick to work in the cause of deepening historical understanding, the historian knows that it is smart to stay on constant alert for these metric moments.

The United States observed the Bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 2004-2006. A particularly lively orchestrator of Bicentennial programs was Clay Jenkinson, a valued collaborator of the Center of the American West. It was my good fortune to spend two very thought-provoking days in Portland, Oregon, at a conference Clay organized. By the time I went to the podium to give my own speech, I was far better educated by all the talks I had heard.

Plus, I had seized scattered moments to write some limericks.

And now to demonstrate my opening claim: Eightseconds, if they feature the right words in the right rhythm, can set history free of conventional thinking.

We will proceed by contrasting the power of the limerick to the power of prose.

Attempted Liberation by Limerick

The order of names is just strange.

There’s no choice, no option, no range.

Clark is just cursed;

Lewis always comes first

In a sequence we can’t rearrange.

Attempted Liberation by Prose

The very words “Lewis and Clark” have become a formula independent of choice, an inflexible assumption, and a pre-programmed code of expectation. Human cognition has many powers; surely a scholar should be able to say to a layperson, “I hope you will join us in the humanities program we have arranged to observe the Bicentennial of Clark and Lewis,” without triggering the response, “Clark and who?” But our neurons and synapses get lodged and locked in patterns of predictability. Indeed, the same conditioning that requires us always to say “Lewis and Clark” (in an order that, unthinkingly, ratifies Thomas Jefferson’s unrelenting elevation of Lewis and dismissal of Clark) also mobilizes the phalanx of clichés and platitudes that will always try to take over our minds when about these two figures who “opened the West,” whatever that could possibly mean in a region of the planet that has been intensively occupied by human beings for centuries.

Commentary from the Undisguised Advocate of Limericks:

Attempt liberation by limerick, and you can enlist your listeners in the cause of opening the door to more expansive historical thought, challenging the assumptions that would otherwise constrain any true engagement with these historical figures. In contrast, attempted liberation by prose requires lecturing the listeners, administering a verbal equivalent of that technique of the old-fashioned schoolmarm: wielding a ruler for an old-style rap on the knuckles. (If I seem to be empowering a historical stereotype with that remark, be assured that Miss Ruth Myers in sixth grade in Banning, California, was no stranger to this technique.)

So, yes, it is my conviction that the limerick works better than the prose, but it’s a conviction based on a lot of field-testing.

Now we’ll settle in for one more round of this exercise of comparing the effectiveness of these two approaches to rescuing historical figures from assumptions that, intentionally or not, reduce their significance.

Attempted Liberation by Limerick

In matters of gender and race,

Lewis and Clark have lost face.

They needed more training

In sexual abstaining

And in acting with multicultural grace.

Attempted Liberation by Prose

The Lewis and Clark Expedition represented an intensely gendered network of social relations, heavily freighted with assumptions about the superiority of civilization to savagery. While we are, of course, aware that the world of the early nineteenth century was very different from our own, we cannot obscure the fact that there was a hierarchy of assumed power in every action that Lewis and Clark and their men took. To the degree that the men suffered from the effects of sexually transmitted diseases, these afflictions were unquestionably tied to exercises of power and privilege over Native peoples.

At this point, surely most readers are now ready to exclaim, “We got your point! Uncle! Give us a break!”

So I will.

Though not instantly.

I still have two more Lewis and Clark limericks for readers to deploy in a “Do Try This at Home” activity. In their unsubtle and ham-handed way, both of these limericks provide the occasion to ask ourselves a crucially important question: “As people who are not steering with great clarity when we wrestle with the ethical issues of the twenty-first century, how much authority do we hold when we attempt to judge Americans of two centuries ago?”

Clark and Lewis Forced to Endure Two More Limericks in Their “Honor”

These leaders have outlived their time.

As heroes, they’re far past their prime.

Their legacy is tattered;

Their reputation, battered,

Since exploring’s now judged to be crime.

If we condemn them as brute, boor, or geek,

Lewis and Clark cannot speak.

They can’t protest or riot;

They are forced to be quiet.

They can’t whisper, or mutter, or shriek.

OK, now answer the question: How much authority do we hold when we attempt to judge Americans of the past? Could it be time to accept a reduction in our claims on authority and to expand our portfolio in humility?

The Limerick Advances on Abraham Lincoln’s Unguarded Flank

In 2020, the question—how should we reckon with the complexity of great leaders in the nation’s past?— has become a subject of great division. Would a well-deployed limerick make this situation better or worse?

Might as well find out.

Abraham Lincoln led the Union to a triumph over the Confederacy, and, in a process that turned out to have more steps and stages than he could have imagined, Lincoln pushed for the end of American slavery.

Abraham Lincoln figured out a lot about governance and politics, but he didn’t figure out how to be perfect. To see just how “not-perfect” his presidency was, you have to pay attention to the American West.

In 2009, I spoke at a conference on “Abraham Lincoln and the West” at the Bill Lane Center at Stanford University. In a grim set of stories I will not retell here, the era of the Civil War was a calamitous time for Indian peoples in the West, with a range of catastrophes from the Bear River Massacre in Southern Idaho to the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado, from the agonizing divisions in the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory to the Long Walk forcing the Navajo from their homeland to the distant Bosque Redondo.

Obviously, Lincoln’s attention was elsewhere. I myself am not inclined to get very judgmental on this count. To say that Lincoln had his hands full with the nation’s descent into disunion is surely an understatement. But we cannot fudge this reality: the wisdom appearing in many of his responses to national dilemmas did not show up much in the West.

To get the full picture of the weak flank that the West presented in Lincoln’s presidential performance, consider the crafty strategy adopted by Doris Kearns Goodwin in her celebrated book, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. This is a book about Lincoln’s brilliance in choosing his cabinet, the heads of the executive branch’s departments.

I was far from the only person with a serious interest in Western history who picked up Team of Rivalsin a pre-existing state of puzzlement. If Goodwin believed that Lincoln’s appointments of cabinet officials demonstrated his genius, what would she have to say about the most important federal officeholders when it came to Western America—Caleb B. Smith and John Palmer Usher, Lincoln’s two thoroughly mediocre Secretaries of the Interior?

So how did Doris Kearns Goodwin, in Team of Rivals, reckon with the fact that Lincoln’ s selections as Secretaries of the Interior presided over agencies that were legendary for their corruption, before and after Lincoln’s presidency?

She barely mentioned Smith or Usher.

Problem solved.

This opens the door to a provocative question: in a forthright reckoning with the variable manifestations of Lincoln’s genius in governance, might a writer of limericks outperform Doris Kearns Goodwin?

How could we reckon with the difficulty Lincoln had—as any president would have had—in dealing effectively with the settler factions and feuds that fractured the Western territories? How could we be forthright in noting the intractable ethical challenge presented by the utterly predictable onslaught of political supporters (not unfairly called “political hacks”) who felt that Lincoln owed them patronage appointments to paid federal offices?

Here are two limericks, given force by the distinctive brevity of this art form, that address the troubles Lincoln faced with the West and the federal bureaucracy. Note that these limericks do not blame Lincoln; instead, they implicitly acknowledge that these problems pre-existed him and would outlast him.

Limericks that Are Braver than Doris Kearns Goodwin

When he dealt with the American West,

Lincoln was not at his best.

As endless distractions,

Western squabbles and factions

Made Lincoln feel glum and depressed.

When it was time to distribute the jobs,

Lincoln was besieged by mobs.

He had to pick among packs

Of small-minded hacks,

Partisan embezzlers and slobs.

Yes, Abraham Lincoln was short of perfection. And the right limericks provide the opportunity to explain why perfection was not in his reach, nor in the reach of anyone else who might have tried to lead this troubled nation in the 1860s.

Dating a Limerick

So how did I get into this line of work?

To begin to answer that question, examine the next limerick and try to guess the year when I wrote it.

How terribly hard to be President,

To be inept, confused, and hesitant.

To be cast off and busted

By the friends that you trusted,

To be laughed at beyond all precedent.

I bet nearly everyone guessed wrong.

And yet some may have made a first move toward the answer, “Very recently,” and then rethought that guess when they thought about the word “hesitant.” There are innumerable adjectives ready to go to work to describe the current occupant of the White House. Every now and then, it would be great to have the word “hesitant” come into play in that enormous psychological thesaurus, maybe especially when it comes to the impulsiveness of Tweeting.

But, so far, no such luck.

In fact, the limerick you have been pondering came into being in 1971. I composed it during my 20th Century American History course at the University of California, Santa Cruz, on the day when my professor was lecturing on the presidency of Warren Harding.

If I had made another choice and if I had given you the second limerick that I composed on that day, you would have had so many clues that guessing wouldn’t have been any fun. (A quick reminder: Harding’s campaign slogan was “A Return to Normalcy,” a phrase to reassure voters as the nation retreated into isolationism after the first world war.)

The Second Warren Harding Limerick, Which Might Be the Peak of My Literary Career

There was an old man named Warren

Who hated all things foreign.

He liked to live normally,

Drunk and informally,

And spend his time gambling and whorin’.

As I believe this limerick demonstrates, in 1971, when all my other life skills were still in chrysalis, I was already a skilled practitioner of the craft of the limerick.

So a brief history of this accelerated achievement seems in order.

I was a senior in college when I happened onto a brilliant strategy for managing my restlessness in classrooms. I feel certain that this idea arose from a childhood spent sporadically in the company of Edward Lear. But I did not keep a diary or journal, and so there is no documentation to support this speculation.

But on to the brilliant strategy. While professors pursued their lesson plans with purpose and self-determination, I took up my own project in purpose and self-determination. The moment I got restless in class, I assigned myself to write a limerick. It would then appear to the professors that I was concentrating very hard—which I truly was. With my mind occupied by auditioning various words and rhymes, I found that I might as well direct my gaze in the direction of the professor. This added up to an entirely excellent arrangement: I looked with such focused concentration at the professor that I was unmistakably the closest listener in the room. When a line in my limerick suddenly cohered, I would seize my pen and witte with intensity, not scribbling notes chaotically, but apparently distilling the lecture in a carefully considered way.

Then, at the end of class, I left with incomplete lecture notes that have vanished from the world and with complete limericks that are still in my possession.

When I graduated from college, my plan to manage classroom restlessness had delivered a result that would prove central to my long-term success. At age twenty-one, I was bilingual: I could write in the manner of the academic monograph, and I could write in the manner of the limerick.

Only a day or two after I had arrived in New Haven for graduate school, a group of graduate students from different fields happened to converge in a courtyard.

In a flurry of names, I heard one person introduce himself as “Jeff Limerick.”

I think you can figure out where this is going.

At this point, the title of this subsection gains a striking new dimension. I was indeed soon “dating a Limerick.”

A life that was poised to stretch in many directions had acquired at least one thread of coherence.

An Enthusiastic Public Speaker, Who Finds Herself Writing a Blog,

Composes A Concluding Self-Indulgent Lament

If I could only go into a room

Where Covid-19 did not loom,

I’d inspire and I’d teach,

I’d banter and I’d preach,

Which I cannot do well when on Zoom.

If you find this blog contains ideas worth sharing with friends, please forward this link to them. If you are reading this for the first time, join our EMAIL LIST to receive the Not my First Rodeo blog every Friday.

Photo Credits:

The Pobble Who Has No Toes courtesy of: http://www.nonsenselit.org/Lear/ll/pobble.html

Abraham Lincoln photo courtesy of: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abraham_Lincoln_O-55,_1861-crop.jpg

Lewis & Clark photo courtesy of: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lewis_and_Clark,_side_by_side.jpg

Edward Lear photo courtesy of: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lear#Portraits

The Lady Chatterleys Lover photo courtesy of: https://americanliterature.com/author/d-h-lawrence/book/lady-chatterleys-lover/summary