BioFrontiers partners with Avery Brewing

BioFrontiers partners with world’s oldest biotech industry: Breweries

In the basement of the Jennie Smoly Caruthers Biotechnology Building on CU-Boulder’s East Campus sits a machine that can sequence roughly 6 billion DNA segments in about a week.

By comparison, human DNA consists of roughly 3 billion bases, and it took more than a decade for the first human genome to be sequenced by an international team of scientists.

The machine, an Illumnia HiSeq2000, is the centerpiece of the BioFrontiers Institute’s Next-Gen Sequencing Facility, and it has become a critical piece of equipment for researchers across campus. But it’s also an important resource for the Front Range’s thriving biotech industry, which routinely relies on the facility for sequencing work.

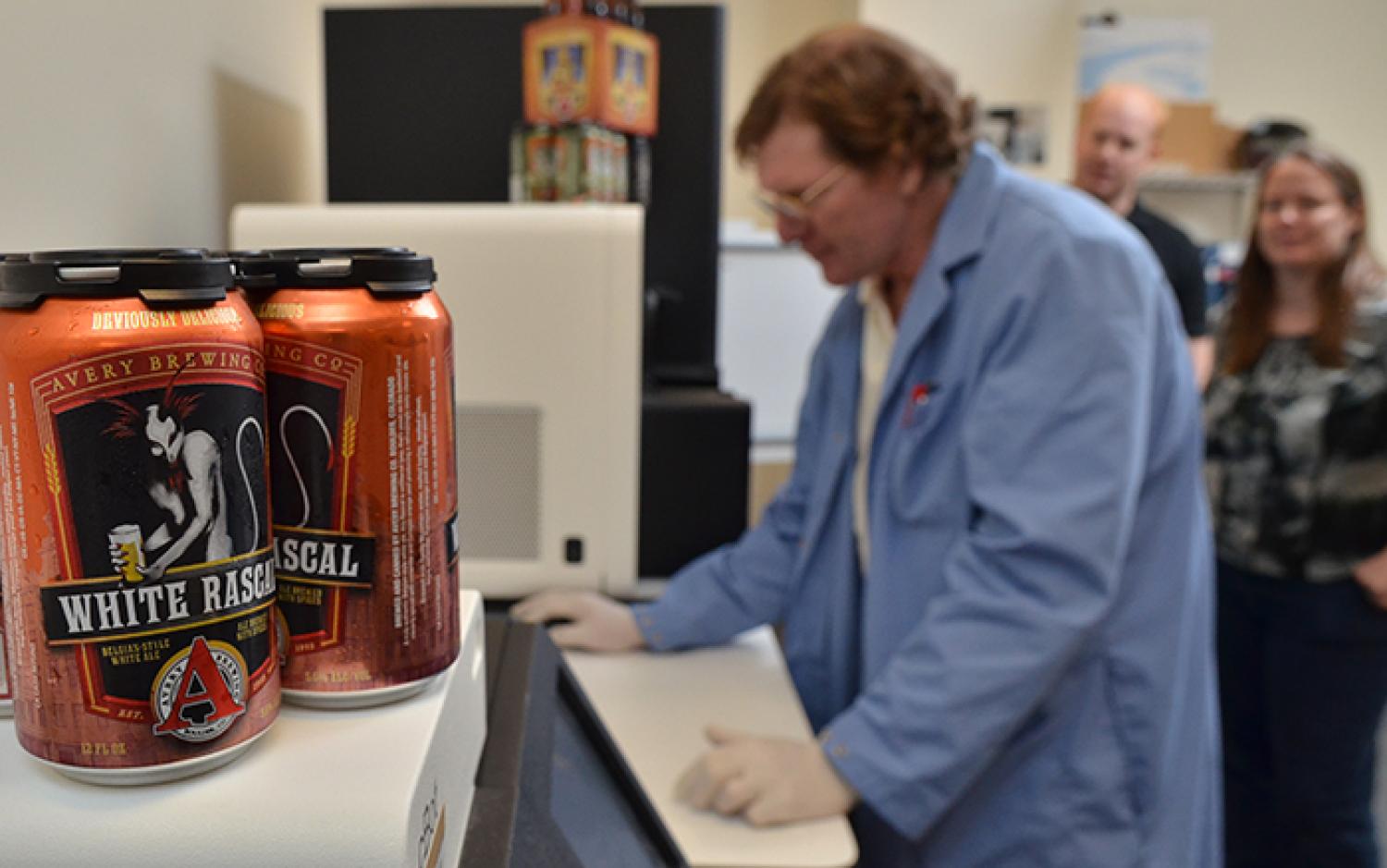

The facility has partnered with all kinds of local biotech big hitters, including a company that makes biofuels and another that makes tests for genetic mutations. But in 2013, the Next-Gen Sequencing Facility forged a new relationship with a well-loved but less-obvious local biotech company: Boulder-based Avery Brewing.

“I would argue that brewing and brewing chemistry is one of the oldest biotechnologies in the world,” said Jim Huntley, director of CU-Boulder’s sequencing facility. “They do a lot of analysis on the quality of their product. Any biotech company does that. I don’t care if you’re making beer or you’re making an enzyme that’s used to catalyze some reaction; there’s always a degree of quality control.”

Huntley and Robin Dowell, an assistant professor at BioFrontiers, are helping Avery find a way to maintain its much-lauded beer quality less expensively by sequencing the genomes of six of the yeast strains used at Avery during the fermentation process.

An IPA that tastes like an IPA

The problem Avery wants to fix is the possible cross-contamination of yeast strains. Unlike large brewing operations, microbreweries use the same equipment to brew multiple types of beer using more than one yeast strain, which can occasionally lead to the yeast strains growing where they don’t belong.

The yeast used in the brewing process feeds on sugar to produce alcohol and carbon dioxide. But along the way, the yeast produces other products that affect the flavor of the beer, including fruity esters, buttery ketones and spicy phenolics. Different strains of yeast produce different flavors, and so using the correct yeast is key to brewing the desired beer.

“For example, our IPA is fermented with a different strain of yeast than our Belgian wit,” said Dan Driscoll, Avery’s staff microbiologist. “We occasionally see our Belgian wit yeast is growing in an IPA tank and that’s a problem because that yeast is incredibly phenolic so the resulting beer smells clovy and spicy. In the interest of consistency, we can’t call our IPA our IPA if it tastes and smells different than the last batch.”

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=4&v=4yehwrdKRGM]

Though it’s rare, when cross-contamination occurs, the entire tank of beer, typically about 240 barrels, has to be flushed.

In the past, Avery has uncovered cases of cross-contamination by sampling the beer while it’s in the fermentation tanks, streaking the sample on an agar plate, putting the plate in an incubator and waiting 48 hours for the yeast to grow.

“What I said, being a microbiologist, when I first got here was, ‘It would be great if we could find a way to both identify this cross-contamination sooner and determine how severe it needs to be in order for us to start picking up on those off flavors,’ ” Driscoll said.

Driscoll, a veteran of the more traditional biotech industry, knew that Avery could purchase a machine that would allow it to quickly differentiate the yeasts based on their genetic codes. But there was a catch: the genetic codes were not known.

Through a connection in the biotech industry, Driscoll got in contact with Huntley, who said he might be able to help Avery with its problem.

“Since we get funding from the state to maintain and operate the facility and purchase equipment, we really want to engage with the local biotech communities and other regional research organizations to provide them access to cutting-edge instrumentation,” Huntley said.

Because Avery uses commercially available yeast strains, and because the microbrew industry has a culture of openly sharing techniques and tools, working with Avery could benefit Colorado’s entire brewing industry, which has a total annual economic benefit to the state of more than $400 million.

‘Think globally, sequence locally’

Avery provided Huntley with six of its yeast strains, including its house ale yeast, which is used in a half dozen of the brewery’s beers. At the Next-Gen Sequencing Facility, Huntley loaded the samples into the HiSeq 2000, which works by shredding multiple copies of the yeast’s DNA into tiny little pieces and then sequencing all those overlapping pieces at the same time to produce a coherent picture of its entire genetic code.

But just knowing the genetic code isn’t enough to solve Avery’s problem. Driscoll also needs to know exactly how the yeasts’ genetic codes differ from each other to be able to tell the yeast strains apart—which is where BioFrontiers researcher Robin Dowell comes in.

Dowell’s lab specializes in differences between yeasts, though she doesn’t typically study the strains that are used to brew beer.

“We focus on two strains that, from a genetic perspective, are about as different as any two random people,” Dowell said. “We look at inter-strain differences all the time, and what Avery really cares about is identifying strain differences they can actually leverage to say, ‘This strain is this one and that strain is that one.’ ”

Once the differences in the strains have been identified, Avery Brewing Company will be able to determine if a tank is contaminated with the wrong kind of yeast in a matter of hours rather than days. The contaminated beer will still have to be flushed, but the test will make it possible for Avery to free up the tank sooner, allowing them to start brewing another beer that they can actually sell.

For the Next-Gen Sequencing Facility, the continued partnership with Avery is just part of what they are charged to do—help strengthen the local biotech community.

“When the local biotech community is stronger, it allows for more startups and more product development, which brings more jobs to the area,” Huntley said. “As I always quip, ‘Think globally, but sequence locally.’ ”