We’re still tasting the spice of 1960s sci-fi

Top illustration: Gary Jamroz-Palma

With this month marking Dune’s 60th anniversary, CU Boulder’s Benjamin Robertson discusses the book’s popular appeal while highlighting the dramatic changes science fiction experienced following its publication

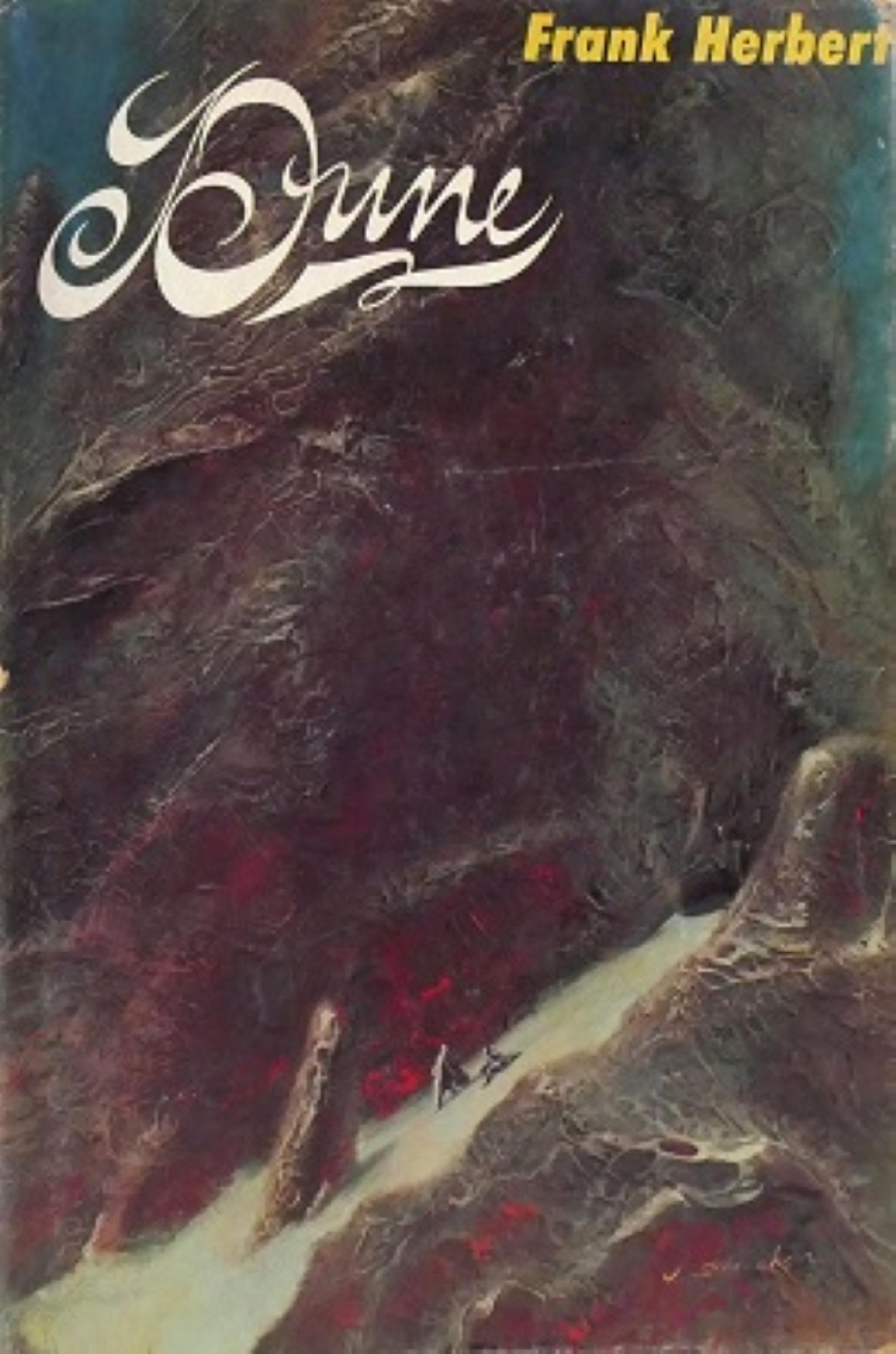

Sixty years ago this month, a novel about a galactic battle over a desert planet valued for its mystical spice forever altered the face of science fiction.

Authored by Frank Herbert, Dune would go on to sell more than 20 million copies, be translated into more than 20 languages and become one of the bestselling science fiction novels of all time, spawning several sequels and movie adaptions that have further boosted its popularity.

Benjamin Robertson, a CU Boulder associate professor of English, pursues a research and teaching focus on genre fiction.

In retrospect, it’s hard to quantify how important Dune was to the genre of science fiction, says Benjamin Robertson, a University of Colorado Boulder Department of English associate professor whose areas of specialty includes contemporary literature and who teaches a science fiction class. That’s because the status Dune attained, along with other popular works at the time, helped transition science fiction from something that was primarily found in specialty magazines to a legitimate genre within the world of book publishing, he says.

Robertson says a number of factors made Dune a remarkable book upon its publication in August 1965, including Herbert’s elaborate world building; its deep philosophical exploration of religion, politics and ecology; and the fact that its plot was driven by its characters rather than by technology. Additionally, the book tapped into elements of 1960s counterculture with its focus on how consuming a spice harvested on the planet Arrakis could allow users to experience mystical visions and enhance their consciousness, Robertson says.

Journey beyond Arrakis with a different kind of dune

“There’s also the element of the chosen one narrative in the book, which is appealing to at least a certain segment of the culture,” he says. The book’s protagonist, Paul Atreides, suffers a great loss and endures many trials before emerging as the leader who amasses power and dethrones the established authorities, he notes.

While Dune found commercial success by blending many different story elements and themes in a new way that engaged readers, it’s worthwhile to consider the book in relation to other works of science fiction being produced in the 1960s, Robertson says. It was during that turbulent time that a new generation of writers emerged, creating works very different from their predecessors in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, which is often considered the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

Whereas many Golden Age science fiction writers tended to set their tales in outer space, to make technology the focus of their stories and to embrace the idea that human know-how could overcome nearly any obstacle, Robertson says many science fiction writers in the 1960s looked to reinvent the genre.

“The 1960s is probably when, for me personally, I feel like science fiction gets interesting,” he says. “I’m not a big fan of what’s called the Golden Age of Science Fiction—the fiction of Asimov or Heinlein. The ‘60s is interesting because of what’s going on culturally, with the counterculture, with student protests and the backlash to the conformities of the 1950s.”

New Wave sci-fi writers make their mark

In 1960s Great Britain, in particular, writers for New Worlds science fiction magazine came to be associated with the term New Wave, which looked inward to examine human psychology and motivations while also tackling topics like sexuality, gender roles and drug culture.

In 1960s Great Britain, in particular, writers for New Worlds science fiction magazine came to be associated with the term New Wave, which looked inward to examine human psychology and motivations while also tackling topics like sexuality, gender roles and drug culture. (Images: moorcography.org)

“This new generation of writers grew up reading science fiction, but they were dissatisfied with both the themes and the way it was written,” Robertson says. “One of the New World’s most notable writers, J.G. Ballard, talked about shifting away from, quote-unquote, outer space to inner space.

“That dovetailed with other writers who weren’t necessarily considered New Wave but were writing soft science fiction that was not focused on technology itself—such as space ships and time travel—but more about exploring the impact of technologies on humanity and on how it changes our relationship with the planet, the solar system and how we relate to each other.”

New Wave authors also wrote about world-ending catastrophes, including nuclear war and ecological degradation. Meanwhile, many British New Wave writers were not afraid to be seen as iconoclasts who challenged established religious and political norms.

“Michael Moorcock, the editor of New Worlds, self-identified as an anarchist, and Ballard was exemplary for challenging authority in his works. He was not just interested in saying, ‘This form of government is bad or compromised, or capitalism is bad, but actually the way we convey those ideas has been compromised,’” Robertson says. “It wasn’t enough for him to identify those systems that are oppressing us; Ballard argued we have to describe them in ways that estranges those ideas.

“And that’s what science fiction classically does—it estranges us. It shows us our world in some skewed manner, because it’s extrapolating from here to the future and imagining …what might a future look like that we couldn’t anticipate, based upon the situation we are in now.”

American science fiction writers might not have pushed the boundaries quite as far their British counterparts, Robertson says, but counterculture ideas found expression in some literature of the time. He points specifically to Harlan Ellison, author of the post-apocalyptic short story “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” who also served as editor of the sci-fi anthology Dangerous Visions, a collection of short stories that were notable for their depiction of sex in science fiction.

Robertson says other American sci-fi writers of the time who embraced elements of the counterculture include Robert Heinlein, whose Stranger in a Strange Land explored the concept of free love, and Philip K. Dick, who addressed the dangers of authority and capitalism in some of his works and whose stories sometimes explored drug use, even as the author was taking illicit drugs to maintain his prolific output.

“Dune definitely broke out into the mainstream—and the fact that Hollywood is continuing to produce movies based upon the book today says something about its staying power,” says CU Boulder scholar Benjamin Robertson.

Meanwhile, Robertson notes that science fiction during the 1960s saw a more culturally diverse group of writers emerge, including Ursula K. Le Guin, the feminist author of such works as The Left Hand of Darkness and The Lathe of Heaven; Madeliene L’Engle, known for her work A Wrinkle in Time; and some lesser-known but still influential writers such as Samuel R. Delaney, one of the first African American and queer science fiction authors, known for his works Babel-17 and Nova.

At the same time, even authors from behind eastern Europe’s Iron Curtain were gaining recognition in the West, including Stanislaw Lem of Poland, author of the novel Solaris, and brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky in the Soviet Union, authors of the novella Ashes of Bikini and many short stories.

Impact of 1960s sci-fi remains long lasting

As the 1960s and 1970s gave way to the 1980s, a new sci-fi genre started to take hold: Cyberpunk. Sharing elements with New Wave, Cyberpunk is a dystopian science fiction subgenre combining advanced technology, including artificial intelligence, with societal collapse.

Robertson says the 1984 debut of William Gibson’s book Neuromancer is widely recognized as a foundational work of Cyberpunk.

While works of 1960s science fiction are now more than five decades old, Robertson says many of them generally have held up well over time.

“Dune definitely broke out into the mainstream—and the fact that Hollywood is continuing to produce movies based upon the book today says something about its staying power,” he says. “I think the works of Ursula K. Le Guin, particularly the Left Hand of Darkness, is a great read and a lot of fun to teach. And Philip K. Dick is always capable of shocking you, not with gore or sex but just with narrative twists and turns.”

If anything, Dick is actually more popular today than when he was writing his books and short stories back in the 1960s, Robertson says, pointing to the fact that a number of them have been made into films—most notably Minority Report and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (which was re-titled Blade Runner).

“At the same time, I think one of the dangers of science fiction is thinking what was written in the 1960s somehow predicts what happens later,” Robertson says. “It can look that way. But, as someone who values historicism, I think it’s important to think about cultural objects in the time they were produced. So, the predictions that Philip K. Dick was making were based upon the knowledge he had in the 1960s, so saying what happened in the 1980s is what he predicted in the 1960s isn’t strictly accurate, because what was happening in the 1980s was coming out of a very different understanding of science, of politics and of technology.

“What I always ask people to remember about science fiction is that it’s about more than the time that it’s written about—it’s about what the future could be, not about what the future actually becomes.”

Did you enjoy this article? Subscribe to our newsletter. Passionate about English? Show your support.